$$\require{cancel} \require{action} \newcommand{\mapsfrom}{\mathrel{\style{display:inline-block; transform:scale(-1,1);}{\longmapsto}}} \bbox[yellow,10pt]{\large {\mathcal I(\alpha, \sqrt 5) = \int\limits_{0}^{\infty} x^{-\alpha \ln x} x^{\sqrt 5} \ln x \, \mathrm dx = \frac{\mathrm e^{1/\alpha}}{\alpha} \sqrt{\frac{\pi}{\alpha}} \, \phi \,\, \mathrm e^{\phi/\alpha},\qquad \alpha > 0} },$$

and, for the case $\color{red}{\boxed{\color{black}{\alpha = 1}}}$,

$$\bbox[yellow,10pt]{\large {\mathcal I(1, \sqrt 5) = \int\limits_{0}^{\infty} x^{-\ln x} x^{\sqrt 5} \ln x \, \mathrm dx = \mathrm e \sqrt{\pi} \, \phi \,\, \mathrm e^{\phi}}}$$

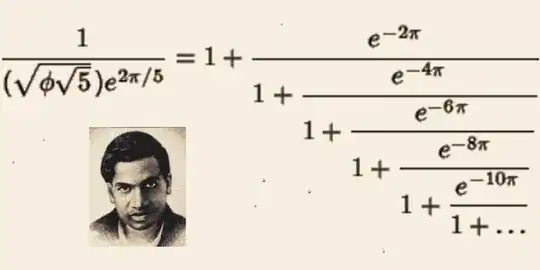

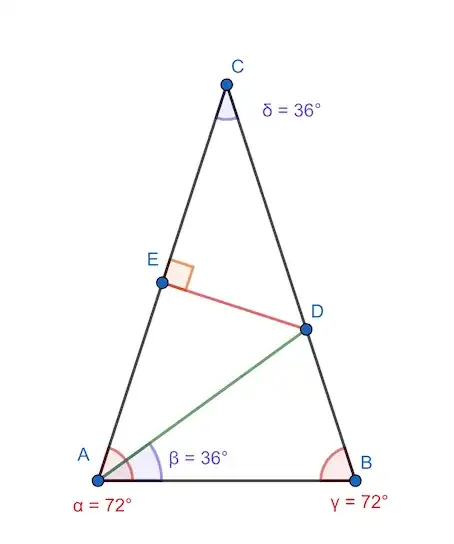

where $\phi := \dfrac{1+\sqrt 5}{2}$ denotes the Golden Ratio.

Consider the generalized integral

$${\large \mathcal I(\alpha, \beta) = \int\limits_{0}^{\infty} x^{-\alpha \ln x} x^{\beta} \ln x \, \mathrm dx \qquad \alpha > 0, \,\,\, \beta \in \mathbb R}:$$

we will obtain the original integral by taking $\beta = \sqrt 5$.

Since $\ln x$ is the term most present in the integral, we can express the first $x$ in terms of the logarithm $\ln x$ using the relation $x = \mathrm e^{\ln x}$, which is true since $\mathrm e(x)$ and $\ln(x)$ are one the inverse function of each other. So, we have:

$$\begin{align}

\mathcal I(\alpha, \beta) &= {\large \int\limits_{0}^{\infty} \bigg(\mathrm e^{\ln x}\bigg)^{-\alpha \ln x} x^{\beta} \ln x \, \mathrm dx} \qquad &\alpha > 0, \,\,\, \beta \in \mathbb R \\

&= {\large \int\limits_{0}^{\infty} \mathrm e^{\ln x \, \cdot \, (- \alpha \ln x)} x^{\beta} \ln x \, \mathrm dx} \qquad &\alpha > 0, \,\,\, \beta \in \mathbb R \\

&= {\large \int\limits_{0}^{\infty} \mathrm e^{- \alpha \ln^2 x} x^{\beta} \ln x \, \mathrm dx} \qquad &\alpha > 0, \,\,\, \beta \in \mathbb R \\

\end{align}$$

Since $\ln x$ is the term most present in the integral and most difficult to handle, we apply the $u$-substitution method with the substitution $u = \ln x$.

$$\text{u}\text{-substitution} \qquad \begin{array}{cc}

&\color{Red}{u = \ln x} & \implies &\color{Blue}{\mathrm du = \dfrac{1}{x} \mathrm dx} \\

&\Big \Updownarrow \, & \quad \,\, &\Big \Updownarrow \\

&\color{Red}{x = \mathrm e^u} &\implies &\color{Blue}{\mathrm dx = \underbrace{\mathrm e^u}_{\color{Red}{\displaystyle x}} \, \mathrm du}.

\end{array}$$

The change of variable causes a change in the lower and upper bounds of integration. The function $\ln x$ is not defined in $x=0$ and $x= \infty$ and its domain is $]0, \infty[$: taking the limits $x \to 0^{+}$ ($\ln x$ is defined for positive $x$) and $x \to \infty$ of $u=\ln x$ boils down:

$$\begin{align}

\text{Lower bound:} \qquad &u_{\text{lower}} = \lim_{x \to 0^{+}} \ln x = - \infty \\

\text{Upper bound:} \qquad &u_{\text{upper}} = \lim_{x \to \infty} \ln x = + \infty.

\end{align}$$

The integral

$$\mathcal I = {\large \int\limits_{\cancelto{\large{-\infty}}{0}}^{\infty} \mathrm e^{- \alpha \, \overbrace{\color{Red}{\ln^2 x}}^{\displaystyle u^2}} \, {\underbrace{\color{Red}{x}}^{\quad \beta}_{\displaystyle \mathrm e^u}} \, \overbrace{\color{Red}{\ln x}}^{\displaystyle u} \, \underbrace{\color{Blue}{\mathrm dx}}_{\displaystyle \mathrm e^u \, \mathrm du}} \qquad \alpha > 0, \,\,\, \beta \in \mathbb R$$

now becomes

$$\begin{align}

\mathcal I &= {\large \int\limits_{-\infty}^{\infty} \mathrm e^{- \alpha u^2} \bigg(\mathrm e^u\bigg)^{\beta} u \, \mathrm e^u \, \mathrm du} \qquad \alpha > 0, \,\,\, \beta \in \mathbb R \\

&= {\large \int\limits_{-\infty}^{\infty} \mathrm e^{- \alpha u^2} \mathrm e^{u \beta} u \, \mathrm e^u \, \mathrm du} \qquad \alpha > 0, \,\,\, \beta \in \mathbb R \\

&= {\large \int\limits_{-\infty}^{\infty} \mathrm e^{- \alpha u^2} \mathrm e^{u \beta \, + \, u} \, u \, \mathrm du} \qquad \alpha > 0, \,\,\, \beta \in \mathbb R,

\end{align}$$

so

$${\large \mathcal I = \int\limits_{-\infty}^{\infty} \mathrm e^{- \alpha u^2 \ + \, u (\beta \, + \, 1)} \, u \, \mathrm du} \qquad \alpha > 0, \,\,\, \beta \in \mathbb R. \tag{INT}\label{INT}$$

The exponent term, $- \alpha u^2 + u (\beta + 1)$, is difficult to handle. The strategy to simplify it and make it easier to handle is to reduce it to a binomial square, since we already have a quadratic term $(u^2)$ and a term in $u$.

The binomial square is of the form

$$\begin{align}

&\underbrace{(\color{Green}{1^{\text{st}} \, \text{term of the binomial square}} + \color{Orange}{2^{\text{nd}} \, \text{term of the binomial square}})^2}_{\displaystyle \text{original structure}} \\ \\

&\hspace{6cm}= \\ \\

&\hspace{3cm}\underbrace{\toggle{\bbox[20pt, Green]{}}{(\color{Green}{1^{\text{st}} \, \text{term of the binomial square}})^2}\endtoggle \, + \, \toggle{\bbox[20pt, GoldenRod]{}}{\color{brown}{2} \cdot \color{Green}{1^{\text{st}} \, \text{term of the binomial square}} \cdot \color{Orange}{2^{\text{nd}} \, \text{term of the binomial square}}}\endtoggle \, + \, \toggle{\bbox[20pt, Orange]{}}{(\color{Orange}{2^{\text{nd}} \, \text{term of the binomial square}})^2}\endtoggle}_{\displaystyle \text{derived structure}}, \tag{$\spadesuit$}\label{spade}

\end{align}$$

where

$$\begin{align}

\color{Green}{1^{\text{st}} \, \text{term of the binomial square}} &\mapsfrom (\color{Green}{1^{\text{st}} \, \text{term of the binomial square}})^2 \tag{1.1} \label{1.1}\\

\color{Orange}{2^{\text{nd}} \, \text{term of the binomial square}} &\mapsfrom (\color{Orange}{2^{\text{nd}} \, \text{term of the binomial square}})^2 \tag{1.2} \label{1.2}

\end{align}$$

with the double product

$$ \color{brown}{2} \cdot \color{Green}{1^{\text{st}} \, \text{term of the binomial square}} \cdot \color{Orange}{2^{\text{nd}} \, \text{term of the binomial square}} \tag{1.3} \label{1.3}.$$

$\text{A)}$ Let us start with the first term of the $\text{derived structure}$.

- $1^{\text{st}}\, \text{term}$: quadratic term. In the expression on the exponent, there is a term comprising $u^2$, so $u^2$ can be taken as the quadratic term of the binomial square we wish to construct. Therefore:

$${\color{green}{\boxed{u^2}}} \quad \text{is the $1^{\text{st}}$ term of the sum.}$$

Despite that, it is bound to $\alpha$ by multiplication. Therefore, to isolate it and keep it positive (i.e., to obtain $u^2$), it is necessary to total factoring $-\alpha$ out. So:

$$- \alpha u^2 + u (\beta + 1)=- \alpha \underbrace{\left(u^2 - \frac{\beta+1}{\alpha} u\right)}_{\eqref{threestar}}. \tag{$\clubsuit$}\label{club}$$

Thus, we want to take $\left(u^2 - \dfrac{\beta+1}{\alpha} u\right)$ to a form similar to $\eqref{spade}$.

$\text{B)}$ Now, let us analyse the $\text{original structure}$.

Since the first term of the $\text{derived structure}$ is $u^2$, by $\eqref{1.1}$ we have

$$u^2 \longmapsto u,$$

so $u$ is the first term of the $\text{original structure}$. Therefore:

$${\color{green}{\boxed{u \quad \text{is the $1^{\text{st}}$ term of the binomial square}}}}.\tag{B}\label{B}$$

$\text{C)}$ Now, let us proceed by examining the second term of the expression $\left(u^2 - \dfrac{\beta+1}{\alpha} u\right)$, since

$${\color{Orange}{\boxed{- \frac{\beta+1}{\alpha}}}} \quad \text{is the $2^{\text{nd}}$ term of the sum.}$$

It is one of the three terms that we want to take to the sum of the three terms that make up the square of a binomial, and it is not quadratic, so it has to be of the form of a double product $2ab$.

Multiplying and dividing the term $- \dfrac{\beta+1}{\alpha} u$ by $2$:

$$\frac{- \color{brown}{2} \, (\beta+1) u}{\color{brown}{2} \, \alpha}. \tag{$\ast$}\label{*}$$

Since the term in the double product form must be $$\color{brown}{2} \cdot \color{Green}{1^{\text{st}} \, \text{term of the binomial square}} \cdot \color{Orange}{2^{\text{nd}} \, \text{term of the binomial square}},$$

and the first term of the binomial square is $u$, as per $\eqref{B}$, we can write $\eqref{*}$ as

$$ \color{brown}{2} \cdot \color{Green}{u} \cdot \left(\color{Orange}{- \frac{\beta+1}{2 \alpha}}\right).$$

Therefore, $\color{Orange}{- \dfrac{\beta+1}{2 \alpha}}$ has to be the second term of the binomial square, so

$${\color{Orange}{\boxed{- \frac{\beta+1}{2 \alpha} \quad \text{is the $2^{\text{nd}}$ term of the binomial square}}}}.\tag{C}\label{C}$$

Therefore, the binomial square under consideration is:

$$

(\color{Green}{1^{\text{st}} \, \text{term of the binomial square}} + \color{Orange}{2^{\text{nd}} \, \text{term of the binomial square}})^2 \\ $$

$$\begin{align}

&= \left[\color{Green}{u}+ \left(\color{Orange}{- \frac{\beta+1}{2 \alpha}}\right)\right]^2 \\

&= \color{Green}{u^2} + \color{brown}{2} \cdot \color{Green}{u} \cdot \left(\color{Orange}{- \frac{\beta+1}{2 \alpha}}\right) + \left(\color{Orange}{- \frac{\beta+1}{2 \alpha}}\right)^2 \\

&= \color{Green}{u^2} - \color{Orange}{\frac{\beta+1}{\alpha}} \color{Green}{u} + \left(\color{Orange}{\frac{\beta+1}{2 \alpha}}\right)^2

\end{align}$$

so

$$\left(u - \frac{\beta+1}{2 \alpha}\right)^2 = u^2 - \frac{\beta+1}{\alpha}u + \left(\frac{\beta+1}{2 \alpha}\right)^2. \tag{$\star$}\label{star}$$

The sum we want to take to a form similar to the binomial square is

$$\text{Sum} = u^2 - \frac{\beta+1}{\alpha} u. \tag{$\star \star$}\label{twostar}$$

We can see that $\eqref{star}$ and $\eqref{twostar}$ are very similar, differing only by a constant $\left(\dfrac{\beta+1}{2\alpha}\right)^2$. Therefore, to make $\eqref{twostar}$ expressible in terms of $\eqref{star}$ without changing its expression, we add and subtract $\left(\dfrac{\beta+1}{2\alpha}\right)^2$ to $\eqref{twostar}$:

$$\begin{align}

\text{Sum} &= u^2 - \frac{\beta+1}{\alpha} u \color{Orange}{+ \left(\frac{\beta+1}{2\alpha}\right)^2 - \left(\frac{\beta+1}{2\alpha}\right)^2} \\

&= \underbrace{\left[u^2 - \frac{\beta+1}{\alpha}u + \left(\frac{\beta+1}{2 \alpha}\right)^2\right]}_{\eqref{star} \,\, := \displaystyle \left(u - \frac{\beta+1}{2 \alpha}\right)^2} - \left(\frac{\beta+1}{2\alpha}\right)^2,

\end{align}$$

so

$$\left(u^2 - \frac{\beta+1}{\alpha} u\right) = \left(u - \frac{\beta+1}{2 \alpha}\right)^2 - \left(\frac{\beta+1}{2\alpha}\right)^2 \tag{$\star\star\star$}\label{threestar}.$$

Substituting $\eqref{threestar}$ into $\eqref{club}$, we obtain

$$- \alpha u^2 + u (\beta + 1)=- \alpha \left[\left(u - \frac{\beta+1}{2 \alpha}\right)^2 - \left(\frac{\beta+1}{2\alpha}\right)^2\right] \tag{$\clubsuit\clubsuit$}\label{twoclub}.$$

Substituting $\eqref{twoclub}$ into $\eqref{INT}$:

$${\large \mathcal I = \int\limits_{-\infty}^{\infty} \mathrm e^{- \alpha \left[\left(u \, - \, \frac{\beta \, + \, 1}{2 \alpha}\right)^2 - \left(\frac{\beta \, + \, 1}{2\alpha}\right)^2\right]} \, u \, \mathrm du} \qquad \alpha > 0, \,\,\, \beta \in \mathbb R.$$

We have:

$$\begin{align}

\mathcal I &= \large{\int\limits_{-\infty}^{\infty} \mathrm e^{- \alpha \left[\left(u \, - \, \frac{\beta \, + \, 1}{2 \alpha}\right)^2 - \left(\frac{\beta \, + \, 1}{2\alpha}\right)^2\right]} \, u \, \mathrm du} \qquad &\alpha > 0, \,\,\, \beta \in \mathbb R \\

&= \large{\int\limits_{-\infty}^{\infty} \mathrm e^{- \alpha \left[\left(u \, - \, \frac{\beta \, + \, 1}{2 \alpha}\right)^2 \right] + \alpha \left(\frac{\beta \, + \, 1}{2\alpha}\right)^2} \, u \, \mathrm du} \qquad &\alpha > 0, \,\,\, \beta \in \mathbb R \\

&= \large{\int\limits_{-\infty}^{\infty} \mathrm e^{- \alpha \left[\left(u \, - \, \frac{\beta \, + \, 1}{2 \alpha}\right)^2 \right]} \cdot \mathrm e^{\alpha \left(\frac{\beta \, + \, 1}{2\alpha}\right)^2} \, u \, \mathrm du} \qquad &\alpha > 0, \,\,\, \beta \in \mathbb R \\

&= \mathrm e^{\alpha \left(\frac{\beta \, + \, 1}{2\alpha}\right)^2} \large{\int\limits_{-\infty}^{\infty} \mathrm e^{- \alpha \left[\left(u \, - \, \frac{\beta \, + \, 1}{2 \alpha}\right)^2 \right]} \, u \, \mathrm du} \qquad &\alpha > 0, \,\,\, \beta \in \mathbb R \\

&= \mathrm e^{\frac{1}{\alpha} \left(\frac{\beta \, + \, 1}{2}\right)^2} \large{\int\limits_{-\infty}^{\infty} \mathrm e^{- \alpha \left[\left(u \, - \, \frac{\beta \, + \, 1}{2 \alpha}\right)^2 \right]} \, u \, \mathrm du} \qquad &\alpha > 0, \,\,\, \beta \in \mathbb R. \\

\end{align}$$

Since $\left(u - \dfrac{\beta + 1}{2 \alpha}\right)$ is the most difficult term to handle, we apply the $u$-substitution method with the substitution $z = u - \dfrac{\beta + 1}{2 \alpha}$.

$$\text{z}\text{-substitution} \qquad \begin{array}{cc}

&\color{Violet}{z = u - \dfrac{\beta + 1}{2 \alpha}} & \implies &\color{Purple}{\mathrm dz = \mathrm du} \\

&\Big \Updownarrow \, & \quad \,\, &\Big \Updownarrow \\

&\color{Violet}{u = z+\dfrac{\beta + 1}{2 \alpha}} &\implies &\color{Purple}{\mathrm du = \mathrm dz}.

\end{array}$$

The change of variable doesn't cause a change in the lower and upper bounds of integration. Taking the limits $u \to -\infty$ and $x \to \infty$ of $z=u-\dfrac{\beta + 1}{2 \alpha}$ boils down:

$$\begin{align}

\text{Lower bound:} \qquad &z_{\text{lower}} = \lim_{u \to -\infty} \left(u-\dfrac{\beta + 1}{2 \alpha}\right) = - \infty \\

\text{Upper bound:} \qquad &z_{\text{upper}} = \lim_{u \to \infty} \left(u-\dfrac{\beta + 1}{2 \alpha}\right) = + \infty.

\end{align}$$

The integral

$$\large{\mathrm e^{\frac{1}{\alpha} \left(\frac{\beta \, + \, 1}{2}\right)^2} \int\limits_{-\infty}^{\infty} \mathrm e^{- \alpha \overbrace{\left[{\color{Violet}{\left(u \, - \, \frac{\beta \, + \, 1}{2 \alpha}\right)^2}}\right]}^{\displaystyle z^2}} \, \underbrace{\color{Violet}{u}}_{z \, + \, \frac{\beta \, + \, 1}{2 \alpha}} \, \underbrace{\color{Purple}{\mathrm du}}_{\mathrm dz}} \qquad \alpha > 0, \,\,\, \beta \in \mathbb R$$

now becomes

$$\begin{align}

\mathcal I &= {\large{\mathrm e^{\frac{1}{\alpha} \left(\frac{\beta \, + \, 1}{2}\right)^2}}\int\limits_{-\infty}^{\infty}} \mathrm e^{- \alpha z^2}\left(z+\frac{\beta + 1}{2 \alpha}\right) \, \mathrm dz \qquad &\alpha > 0, \,\,\, \beta \in \mathbb R \\

&= {\large{\mathrm e^{\frac{1}{\alpha} \left(\frac{\beta \, + \, 1}{2}\right)^2}\int\limits_{-\infty}^{\infty}}} \left[\mathrm e^{- \alpha z^2} \cdot z + \mathrm e^{- \alpha z^2} \cdot \frac{\beta+1}{2\alpha}\right] \, \mathrm dz \qquad &\alpha > 0, \,\,\, \beta \in \mathbb R \\

&= {\large{\mathrm e^{\frac{1}{\alpha} \left(\frac{\beta \, + \, 1}{2}\right)^2}}}\left[{\large{\int\limits_{-\infty}^{\infty}}} \mathrm e^{- \alpha z^2} \cdot z \, \mathrm dz + {\large{\int\limits_{-\infty}^{\infty}}} \mathrm e^{- \alpha z^2} \cdot \frac{\beta+1}{2\alpha}\, \mathrm dz \right] \qquad &\alpha > 0, \,\,\, \beta \in \mathbb R \\

&= {\large{\mathrm e^{\frac{1}{\alpha} \left(\frac{\beta \, + \, 1}{2}\right)^2}}}\left[\underbrace{{\large{\int\limits_{-\infty}^{\infty}}} z \, \mathrm e^{- \alpha z^2} \, \mathrm dz}_{\displaystyle \mathcal I_1} \, + \, \underbrace{{\large{\int\limits_{-\infty}^{\infty}}} \frac{\beta+1}{2\alpha} \mathrm e^{- \alpha z^2} \, \mathrm dz}_{\displaystyle \mathcal I_2} \right] \qquad &\alpha > 0, \,\,\, \beta \in \mathbb R \tag{$\diamondsuit$}\label{diamond},

\end{align}$$

with

$$\mathcal I_1 := {\large{\int\limits_{-\infty}^{\infty}}} z \, \mathrm e^{- \alpha z^2} \, \mathrm dz \tag{I1} \label{I1}$$

and

$$\mathcal I_2 := {\large{\int\limits_{-\infty}^{\infty}}} \frac{\beta+1}{2\alpha} \mathrm e^{- \alpha z^2} \, \mathrm dz \tag{I2} \label{I2}$$.

Evaluation of $\eqref{I1}$:

Let $f(z) = z \, \mathrm e^{- \alpha z^2}, \quad \alpha \gt 0$. We note that

$$\begin{align}

f(z) &= z \, \mathrm e^{- \alpha z^2}, \qquad \alpha \gt 0 \\

&= -\left[-z \, \mathrm e^{- \alpha z^2}\right], \qquad \alpha \gt 0\\

&= -\left[-z \, \mathrm e^{- \alpha (-z)^2}\right], \qquad \alpha \gt 0 \\

&= - \underbrace{\left[(-z) \, \mathrm e^{- \alpha (-z)^2}\right]}_{\displaystyle f(-z)}, \qquad \alpha \gt 0 \\

&= - f(-z),

\end{align}$$

so $f(z) = - f(-z)$, or $-f(z) = f(-z)$, which is the definition of an odd function.

So:

$$f(z) = z \, \mathrm e^{- \alpha z^2}, \,\, \alpha \gt 0 \quad \text{is an odd function}.$$

Now, let us state the following

Theorem. Let $f(z)$ be an odd function with a primitive on the open interval $]−a, a[$, where $a \in \mathbb{R}^{+}, a \in \overline{\mathbb{R}}$, with $\overline{\mathbb{R}} = \mathbb R \cup \left\{-\infty, + \infty \right\}$. Then:

$${\large{\int\limits_{-a}^{a}}f(z) \, \mathrm dz} = 0$$

Choosing $a = + \infty$, we have

$${\large{\int\limits_{-\infty}^{+\infty}}} f(z) \, \mathrm dz = 0 \qquad \text{with} \,\, f(z) \,\, \text{odd function}.$$

Since $f(z) = z \, \mathrm e^{- \alpha z^2}, \,\, \alpha \gt 0$ is an odd function, we have

$${\large{\int\limits_{-\infty}^{+\infty}}} z \, \mathrm e^{- \alpha z^2} \, \mathrm dz = 0, \qquad \alpha \gt 0.$$

So:

$$\boxed{\mathcal I_1 := {\large{\int\limits_{-\infty}^{+\infty}}} z \, \mathrm e^{- \alpha z^2} \, \mathrm dz = 0}, \qquad \alpha \gt 0. \tag{I1*}\label{I1*}$$

Evaluation of $\eqref{I2}$:

$$\begin{align}

\mathcal I_2 :&= {\large{\int\limits_{-\infty}^{\infty}}} \frac{\beta+1}{2\alpha} \mathrm e^{- \alpha z^2} \, \mathrm dz, \qquad &\alpha > 0, \,\,\, \beta \in \mathbb R \\

&= \frac{\beta+1}{2\alpha} {\large{\int\limits_{-\infty}^{\infty}}} \mathrm e^{- \alpha z^2} \, \mathrm dz, \qquad &\alpha > 0, \,\,\, \beta \in \mathbb R \\

&= \frac{\beta+1}{2\alpha} {\large{\int\limits_{-\infty}^{\infty}}} \mathrm e^{- (\sqrt\alpha)^2 \, z^2} \, \mathrm dz, \qquad &\alpha > 0, \,\,\, \beta \in \mathbb R \\

&= \frac{\beta+1}{2\alpha} {\large{\int\limits_{-\infty}^{\infty}}} \mathrm e^{- (\sqrt\alpha \, z)^2} \, \mathrm dz, \qquad &\alpha > 0, \,\,\, \beta \in \mathbb R \\

&= \frac{\beta+1}{2\alpha} {\large{\int\limits_{-\infty}^{\infty}}} \mathrm e^{- (\sqrt\alpha \, z)^2} \color{Red}{\frac{\color{Red}{\sqrt a}}{\color{Red}{\sqrt a}}} \, \mathrm dz, \qquad &\alpha > 0, \,\,\, \beta \in \mathbb R \\

&= \frac{\beta+1}{2\alpha} \cdot \frac{1}{\sqrt{\alpha}} {\large{\int\limits_{-\infty}^{\infty}}} \mathrm e^{- (\sqrt\alpha \, z)^2} \sqrt \alpha, \qquad &\alpha > 0, \,\,\, \beta \in \mathbb R \\

&= \frac{\beta+1}{2} \cdot \frac{1}{\alpha \, \sqrt\alpha} \underbrace{{\large{\int\limits_{-\infty}^{\infty}}} \sqrt \alpha \, \mathrm e^{- (\sqrt\alpha \, z)^2}}_{\displaystyle \text{Gaussian integral}}, \qquad &\alpha > 0, \,\,\, \beta \in \mathbb R \\

&= \frac{\beta+1}{2} \cdot \frac{1}{\alpha \, \sqrt\alpha} \cdot \toggle{\bbox[Red, 10pt]{\text{Gaussian Integral}}}{\sqrt \pi}\endtoggle, \qquad &\alpha > 0, \,\,\, \beta \in \mathbb R \\

&= \frac{\beta+1}{2} \cdot \frac{1}{\alpha \, \sqrt\alpha} \cdot \sqrt \pi, \qquad &\alpha > 0, \,\,\, \beta \in \mathbb R \\

&= \frac{\sqrt \pi}{\alpha \, \sqrt\alpha} \cdot \frac{\beta+1}{2}, \qquad &\alpha > 0, \,\,\, \beta \in \mathbb R

\end{align}.$$

So:

$$\boxed{\mathcal I_2 := {\large{\int\limits_{-\infty}^{\infty}}} \frac{\beta+1}{2\alpha} \mathrm e^{- \alpha z^2} \, \mathrm dz = \frac{\sqrt \pi}{\alpha \, \sqrt\alpha} \cdot \frac{\beta+1}{2}}, \qquad \alpha > 0, \,\,\, \beta \in \mathbb R. \tag{I2*}\label{I2*}$$

Substituting $\eqref{I1*}$ and $\eqref{I2*}$ into $\eqref{diamond}$:

$$\begin{align}

\mathcal I(\alpha, \beta) &= {\large{\mathrm e^{\frac{1}{\alpha} \left(\frac{\beta \, + \, 1}{2}\right)^2}}}\left[\underbrace{0}_{\displaystyle \mathcal I_1} + \underbrace{\frac{\sqrt \pi}{\alpha \, \sqrt\alpha} \cdot \frac{\beta+1}{2}}_{\displaystyle\mathcal I_2}\right], \qquad &\alpha > 0, \,\,\, \beta \in \mathbb R \\

&= {\large{\mathrm e^{\frac{1}{\alpha} \left(\frac{\beta \, + \, 1}{2}\right)^2}}} \cdot \frac{\sqrt \pi}{\alpha \, \sqrt\alpha} \cdot \frac{\beta+1}{2}, \qquad &\alpha > 0, \,\,\, \beta \in \mathbb R.

\end{align}$$

So:

$$\mathcal I(\alpha, \beta) = {\large{\mathrm e^{\frac{1}{\alpha} \left(\frac{\beta \, + \, 1}{2}\right)^2}}} \frac{\sqrt \pi}{\alpha \, \sqrt\alpha} \frac{\beta+1}{2}, \qquad \alpha > 0, \,\,\, \beta \in \mathbb R. $$

Since we obtain the original integral by taking $\beta = \sqrt 5$, substituting this value into the previous expression:

$$\begin{align}

\mathcal I(\alpha, \sqrt 5) &= {\large{\mathrm e^{\frac{1}{\alpha} \left(\frac{\sqrt 5 \, + \, 1}{2}\right)^2}}} \cdot \frac{\sqrt \pi}{\alpha \, \sqrt\alpha} \cdot \frac{\sqrt 5+1}{2}, \qquad &\alpha > 0 \\

&= {\large{\mathrm e^{\frac{1}{\alpha} \left(\underbrace{\frac{\sqrt 5 \, + \, 1}{2}}_{\displaystyle \phi}\right)^2}}} \frac{\sqrt \pi}{\alpha \, \sqrt\alpha} \underbrace{\frac{\sqrt 5+1}{2}}_{\displaystyle \phi}, \qquad &\alpha > 0 \\

&= {\large{\mathrm e^{\frac{1}{\alpha} \phi^2}}} \frac{\sqrt \pi}{\alpha \, \sqrt\alpha} \phi, \qquad &\alpha > 0. \tag{FI} \label{FI}\\

\end{align}$$

It can be shown that if $\phi := \dfrac{\sqrt 5+1}{2}$, then $\phi^2 = \phi +1.$ Substituting $\phi +1$ into $\eqref{FI}$, we obtain:

$$\begin{align}

\mathcal I(\alpha, \sqrt 5) &= {\large{\mathrm e^{\frac{1}{\alpha} \phi^2}}} \frac{\sqrt \pi}{\alpha \, \sqrt\alpha} \phi, \qquad &\alpha > 0 \\

&= {\large{\mathrm e^{\frac{1}{\alpha}(\phi +1)}}} \frac{\sqrt \pi}{\alpha \, \sqrt\alpha} \phi, \qquad &\alpha > 0 \\

&= {\large{\mathrm e^{\left(\frac{\phi}{\alpha}+\frac{1}{\alpha}\right)}}} \frac{\sqrt \pi}{\alpha \, \sqrt\alpha} \phi, \qquad &\alpha > 0 \\

&= {\large{\mathrm e^{\frac{\phi}{\alpha}} \cdot \mathrm e^{\frac{1}{\alpha}}}} \frac{\sqrt \pi}{\alpha \, \sqrt\alpha} \phi, \qquad &\alpha > 0 \\

&= \frac{\mathrm e^{1/\alpha}}{\alpha} \frac{\sqrt{\pi}}{\sqrt{\alpha}} \, \phi \,\, \mathrm e^{\phi/\alpha},\qquad &\alpha > 0 \\

&= \frac{\mathrm e^{1/\alpha}}{\alpha} \sqrt{\frac{\pi}{\alpha}} \, \phi \,\, \mathrm e^{\phi/\alpha},\qquad &\alpha > 0.

\end{align}$$

So:

$$\bbox[10px,#f3f3f3, border:5px dotted #251874]{\large {\mathcal I(\alpha, \sqrt 5) = \int\limits_{0}^{\infty} x^{-\alpha \ln x} x^{\sqrt 5} \ln x \, \mathrm dx = \frac{\mathrm e^{1/\alpha}}{\alpha} \sqrt{\frac{\pi}{\alpha}} \, \phi \,\, \mathrm e^{\phi/\alpha},\qquad \alpha > 0}}.$$

Substituting $\alpha = 1$ into the previous expression:

$$\mathcal I(1, \sqrt 5) = \frac{\mathrm e^{1/1}}{1} \sqrt{\frac{\pi}{1}} \, \phi \,\, \mathrm e^{\phi/1},$$

i.e.

$$\mathcal I(1, \sqrt 5) = \mathrm e \sqrt{\pi} \, \phi \,\, \mathrm e^{\phi}.$$

Finally:

$$\bbox[10px,#f4f7f8, border:5px dashed #376521]{\large {\mathcal I(1, \sqrt 5) = \int\limits_{0}^{\infty} x^{-\ln x} x^{\sqrt 5} \ln x \, \mathrm dx = \mathrm e \sqrt{\pi} \, \phi \,\, \mathrm e^{\phi}}}.$$