This version is for those, who prefer a different notation. $$ u \circ \sigma = f, \text { where } \sigma(x,y) = \left(\sqrt{x^2+y^2}, \arctan\frac yx\right)$$

Fix $a=(x,y) = r(\cos\theta,\sin\theta)$. Let $(Df)(a)$ and $(\nabla f)(a)$ denote the linear operator and the vector representing it. By the chain rule,

$$(Df)(a) = (Du)(\sigma(a)) \circ (D\sigma)(a).$$

Implying that

\begin{align} (\nabla f)(a) &= (\nabla u)(\sigma(a))\cdot \pmatrix{ \cos\theta & \sin\theta \\ -\frac 1 r\sin\theta & \frac 1r\cos\theta} \\

&= u_r(\sigma(a))\cdot(\cos\theta , \sin\theta) + \frac 1r u_{\theta}(\sigma(a))\cdot(-\sin\theta, \cos \theta).

\end{align}

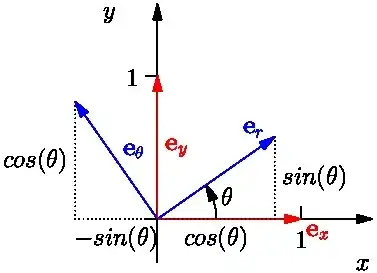

Let's hold on for a minute and observe our result: The vector $(\nabla f)(a)$ is a linear combination of the vectors $(\cos\theta,\sin\theta)$, and $(-\sin\theta, \cos\theta)$.

In fact, \begin{align}\{\, \boldsymbol{e_r} &= (\cos\theta,\sin\theta)\\ , \boldsymbol{e_{\theta}} &= (-\sin\theta, \cos\theta)\}\end{align} is a basis for $\mathbb R^2$. Using our new notation, the equation above becomes

$$ (\nabla f)(a) = u_r(\sigma(a))\cdot \boldsymbol{e_r} + \frac 1r u_{\theta}(\sigma(a))\cdot \boldsymbol{e_{\theta}} = \left(u_r(\sigma(a)), \frac 1r u_{\theta}(\sigma(a))\right) = (\nabla(u))(\sigma(a))\cdot\pmatrix{1 \\ \frac 1r},$$

or equivalently,

$$ (\nabla f)(r(\sin\theta, \cos\theta)) = \left(u_r(r, \theta), \frac 1r u_{\theta}(r, \theta)\right) = (\nabla u)(r,\theta)\cdot\pmatrix{1 \\ \frac 1r}. $$

If we start omitting a few variables, things become prettier, but also somewhat easier to misunderstand.

$$ \nabla f = \nabla u \cdot \pmatrix{1 \\ \frac 1r} = \left(u_r, \frac 1r u_{\theta}\right) = \boldsymbol{e_r} u_r + \boldsymbol{e_{\theta}} \frac 1r u_{\theta} =\boldsymbol{e_r} \frac{\partial u}{\partial r}+ \boldsymbol{e_{\theta}}\frac 1r \frac{\partial u}{\partial \theta} $$

We can also omit function names, leading to

$$ \nabla = \boldsymbol{e_r} \frac{\partial}{\partial r}+ \boldsymbol{e_{\theta}} \frac 1r \frac{\partial}{\partial \theta}. $$