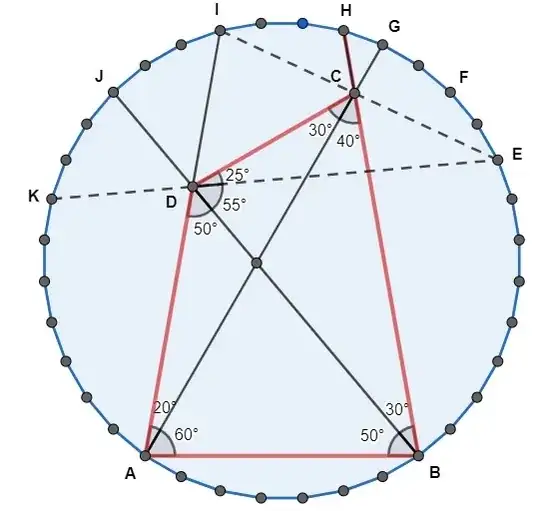

$\textit{Fig. 1 : Quadrilateral $ABCD$ of the Langleys 80-80-20 problem}$$\textit{inside a regular polygon with 36 vertices}$$\textit{This figure is just an introduction ; proceed now to Fig. 2}.$

A now classical question (the $80-80-20$ problem, as mentionned in the second figure here, is frequently posted on this site, for example some days ago here.

Although I know that this type of question is solved by angle chasing (with construction of auxiliary points or lines), I have attempted to see if this issue can be settled in the framework of diagonals belonging to a certain regular $n$-gon. As the GCD of all angles is $10°$, I chose $n=36$, and made use of the theorem of the inscribed angle (in particular the fact that the center angle is twice the inscribed angle sustending a same arc). I arrived in this way at figure $1$. The purpose was, I would say, recreational, because it couldn't achieve a better solution (with the added fact that line segment $CD$ isn't part of a diagonal of the $36$-gon).

But, working on figure $1$, I discovered a property which is summarized in figure $2$ :

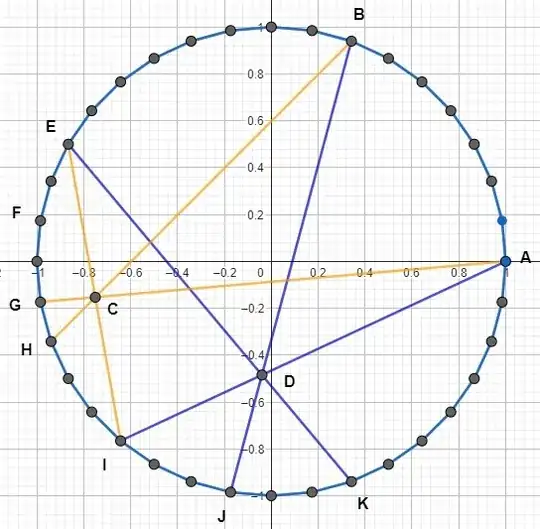

$$\text{The 3 (orange) chords } \ AG, \ BH ,\ EI \ \ \text{are concurrent}\tag{1}$$

and $$\text{The 3 (blue) chords } \ AJ, \ BJ, \ EK \ \ \text{are concurrent.}\tag{2}$$

$\textit{Fig. 2 : With the same points as in figure 1}$ $\textit{highlighting the intersecting chords triples (orange) (1) and (blue) (2).}$

Please note that figure 2 is the same as figure 1, but "installed" into a certain coordinate system : the polygon has unit radius and point $A$ has coordinates $(1,0)$ (the idea behind that : allowing the representation of each vertex of the polygon by a $36$-th root of unity $\omega^k$ where $\omega= e^{i \pi/18}$).

Question 1 : How to prove (1) and (2) in a rigorous way ?

Till now, I have only be able to check (1) and (2) in a numerical way. In particular, my attempts with $n$-th roots of unity haven't been successful.

Question 2 : Beyond question 1, are there other concurrent chords triples in a regular convex $36$-gon (of course different from those obtained by simple rotation...) ? More generally, what can be said about such concurrent triples for a general regular convex $n$-gon ?

Edit : answer to question 1, which amounts to prove the answer given by Blue.

Let us consider 3 diagonals

$$[M_p,M_q], \ \ [M_r,M_s], \ \ [M_u,M_v], \ \ $$

with the conventional notation $M_k=(\cos(ka),\sin(ka))$ where $a=\tfrac{2 \pi}{k}$.

The resp. equations of the corresponding lines for a regular $n$-gon are:

$$\begin{cases} x \cos \tfrac{(p+q)\pi}{2n} + y \sin \tfrac{(p+q)\pi}{2n} + \cos \tfrac{(p-q)\pi}{2n} &=&0\\ x \cos \tfrac{(r+s)\pi}{2n} + y \sin \tfrac{(r+s)\pi}{2n} + \cos \tfrac{(r-s)\pi}{2n} &=&0\\ x \cos \tfrac{(u+v)\pi}{2n} + y \sin \tfrac{(u+v)\pi}{2n}+ \cos \tfrac{(u-v)\pi}{2n} &=&0 \end{cases}\tag{3}$$

(think indeed that for example, in isoceles triangle $M_pOM_q$, where $O$ is the center of the circle, the altitude $OH$ issued from $O$, normal to line $M_pM_q$ has the same direction as the angle bissector of angle $M_pOM_q$ and this bissector has polar angle $\tfrac{(p+q)\pi}{2n}$ ; besides, distance $OH = \cos \tfrac{(p-q)\pi}{2n}$.

In the discussion of a system like (3), the only way it can have a solution is by being redundant which is equivalent to having its main determinant equal to $0$. Therefore, here is a necessary and sufficient condition of intersection of the 3 diagonals :

$$\det \pmatrix{ \cos \tfrac{(p+q)\pi}{2n}&\sin \tfrac{(p+q)\pi}{2n}& \cos \tfrac{(p-q)\pi}{2n}\\ \cos \tfrac{(r+s)\pi}{2n}&\sin \tfrac{(r+s)\pi}{2n}& \cos \tfrac{(r-s)\pi}{2n}\\ \cos \tfrac{(u+v)\pi}{2n}&\sin \tfrac{(u+v)\pi}{2n}& \cos \tfrac{(u-v)\pi}{2n} }=0 \tag{4}$$

Remark: Let $C$ be the common point of these 3 diagonals. Condition (4) allows $C$ outside the polygon. These cases can be cancelled by obtaining the coordinates of $C$ using an element of the kernel $(a,b,c)^T$ of the previous matrix : if $c \ne 0$, the common point is $(a/c,b/c)$ ; otherwise, if $c=0$, it means that $C$ is at infinity, i.e., the diagonals are all parallel.

Condition (4) can be given a complex version by setting $\alpha:=e^{i \pi/n}$ as follows.

$$\det \pmatrix{ \alpha^{(p+q)}&\alpha^{-(p+q)}&(\alpha^{(p-q)}+\alpha^{-(p-q)})\\ \alpha^{(r+s)}&\alpha^{-(r+s)}&(\alpha^{(r-s)}+\alpha^{-(r-s)})\\ \alpha^{(u+v)}&\alpha^{-(u+v)}&(\alpha^{(u-v)}+\alpha^{-(u-v)})\\ }=0$$

Remark: Condition (4) on the nullity of the determinant could have been obtained in a different way : indeed, there is formula for the area of the triangle knowing the equations of its sides that can be found here with a proof by ... Blue, involving the square of the determinant we have used. It is therefore equivalent to express that the area is $0$ and that the three chords concur.