I was trying to think about why in instances like $\cos(0)$ and $\sin(90)$ that the triangle formed in the unit circle becomes degenerate-that is, it collapses into a line.

I am aware that this sounds like a previous question I asked: How would you describe a triangle with a sin 90 based on the definition of sine? However, while that question was asking how to describe a triangle with $\sin(90)$, this question is about explaining why it is that way. Specifically, I thought of a reason to explain this easily using prior knowledge and previous answers to similar questions.

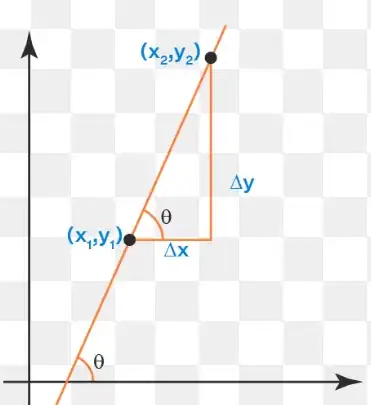

It was helpful to me to visualize coordinates in the unit circle as just being representations of the slopes of lines. The $y$-coordinate would be the rise and the $x$-coordinate would be the run of a given line in the circle. Therefore, as the slope of the line becomes steeper, the rise increases and the run decreases, and likewise, the opposite happens when the line becomes less steep.

At sin(90), the line becomes vertical. You cannot have a triangle with two right angles (this just ends up forming a line), as brought up in Why is the cosine of a right angle, 90 degrees, equal to zero?.

Knowing that at $\sin(90)$, the line formed is a vertical line because it is perpendicular to the $x$-axis, I also started thinking about properties of vertical lines and remembered that vertical lines have an undefined slope-that is, rise but not run.

Combining the two definitions, I concluded that the reason for vertical lines having an undefined slope is because trying to construct a right triangle to find the slope results in a degenerate triangle (that is, there cannot be both rise and run).

As this triangle cannot be constructed from vertical lines, vertical lines evidently have a rise but not a run, so by Pythagorean Theorem $0^2+y^2=c^2$, where $y$=opposite (rise) and $c$=hypotenuse, and $y=c$. Therefore, $\sin(90)=1$, and this sort of thing can also be applied to other angles like $0$ and $180$. I just used $90$ degrees for this example because I feel that it is easier to visualize.

What I was wondering is, am I correct to assume that, for the purpose of explaining this to myself, that there is a correlation between the slope of vertical (or horizontal) lines and the formation of degenerate triangles? In other words, does the fact that triangles cannot have angle measures of $90$-$90$-$0$ mean that vertical lines have an undefined slope (lack of change in the $x$-coordinate or "adjacent" side) and that horizontal lines have a $0$ slope (lack of change in the $y$-coordinate or "opposite" side)? Or am I way off? I was trying to find a different way to explain the concept of $\sin(90)$ and $\cos(0)$ and other angles to myself, especially as someone who enjoys algebra and graphs and can visualize things this way.

Thanks and sorry if this question is vague. Please let me know if I can improve it.

Note: When I say a triangle I am referring to one formed by the rise and run of a line, with the line as the hypotenuse.

As this sort of triangle cannot be formed for vertical or horizontal lines (like those forming $\sin(90)$ or $\cos(0)$), these lines do not have both rise and run, meaning that either the adjacent or opposite side equals the hypotenuse.