I understand this problem is similar to the following question: How would a triangle for sin 90 degree look

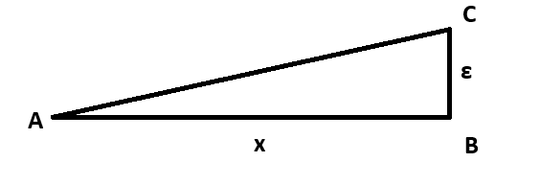

However, I am confused on how sine 90 is defined based on the definition of sine: opposite/hypotenuse. There were two explanations I heard:

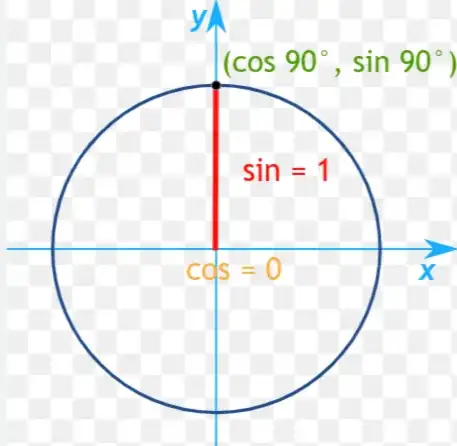

The first is that in a right triangle, the angle opposite the right angle is the same as the hypotenuse, so hypotenuse/hypotenuse=1. I used to be sure about this explanation, but then I heard that the opposite side or adjacent side cannot be the hypotenuse of a right triangle. Also, this does not seem to make sense in regards to a unit circle. In a unit circle, when finding the sine of an acute angle, the right angle is located opposite the origin:

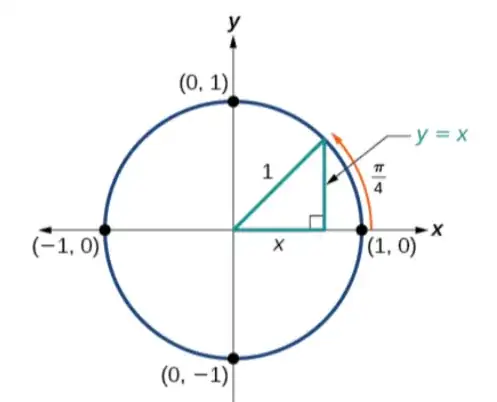

In the unit circle, the angle in the right triangle whose sine is being measured is located at the origin, which means when measuring sin 90 in a right triangle in the unit circle, there will be two right angles in the triangle, correct? From what I know this is not possible, so the triangle will sort of collapse into a line.

The unit circle explanation is that the opposite side gets larger and larger as the angle at the origin nears 90 degrees, while the adjacent side gets smaller and smaller, until the opposite side and the hypotenuse are the same (opposite side becomes equal to 1).

Essentially, the unit circle explanation seems easier to visualize, but is the first one still valid? The only reason I am asking this is because the first explanation seems to create a regular right triangle, but the second creates a triangle that is really just a line. Maybe this is a basic question and can be answered easily, but I am really confused on this. Hopefully the question makes sense, but if not, please let me know. Thanks.