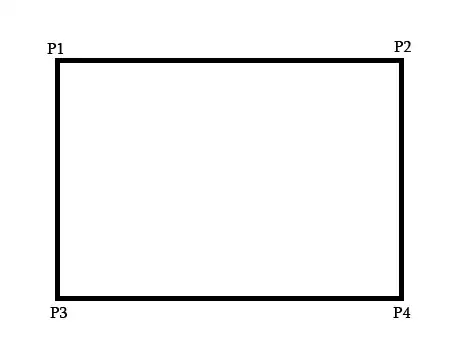

Explaining how to obtain the linear system of equations:

From $P^{\prime}=HP$, we have

$$\begin{bmatrix}u_i\\ v_i\\ 1\end{bmatrix}=\begin{bmatrix}h_1 & h_2 & h_3\\ h_4 & h_5 & h_6\\ h_7 & h_8 & h_9\end{bmatrix}\begin{bmatrix}x_i\\ y_i\\ 1\end{bmatrix}$$

from which we get

$\begin{align}

u_i=h_1x_i+h_2y_i+h_3 & \quad (1)\\

v_i=h_4x_i+h_5y_i+h_6 & \quad (2)\\

1=h_7x_i+h_8y_i+h_9 & \quad (3)\\

\end{align}$

- $(1) / (3)$ and rearranging gives $h_7x_iu_i+h_8y_iu_i+h_9u_i-h_1x_i-h_2y_i-h_3=0$

- $(2) / (3)$ and rearranging gives $h_7x_iv_i+h_8y_iv_i+h_9v_i-h_4x_i-h_5y_i-h_6=0$

Hence, each pair of points $p_i^{\prime} = \begin{bmatrix}u_i\\ v_i\\ 1\end{bmatrix}, p_i = \begin{bmatrix}x_i\\ y_i\\ 1\end{bmatrix}$, we get $2$ equations.

From $4$ pair of points we get linear system with $2\times 4 = 8$ equations, for $8$ unknowns $h_1,h_2,\ldots,h_8$.

Projective Transform (Homography) having $8$ degrees of freedom, $h_9$ is known or can be obtained from the unknown coefficients, so we have to solve for $8$ unknowns.

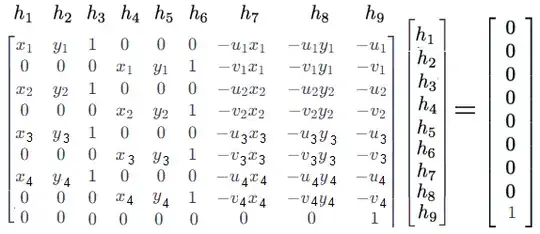

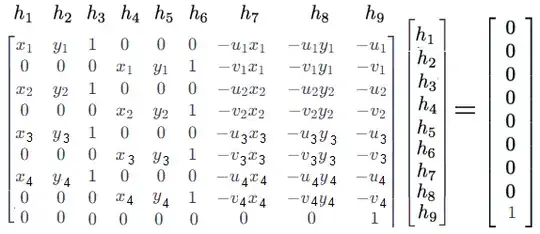

If we assume $h_9=1$, then we have the following linear system of equation ($A\boldsymbol{h}=\boldsymbol{b}$) to solve:

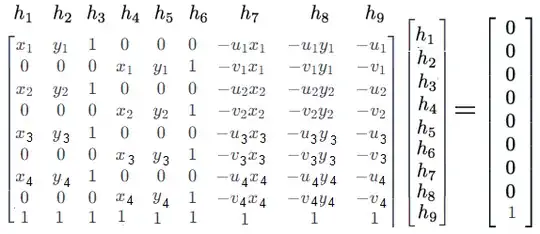

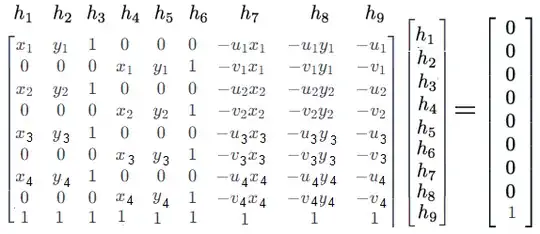

If we assume $\sum\limits_{i=1}^{9}h_i=1$, then we have the following linear system of equation

Assuming $A$ is full-rank, the system has a unique solution and can be obtained as $\boldsymbol{h}=A^{-1}\boldsymbol{b}$, or, more generally, as $\boldsymbol{h}=A^{\dagger}\boldsymbol{b}$, using the Moore-Penrose Pseudoinverse.

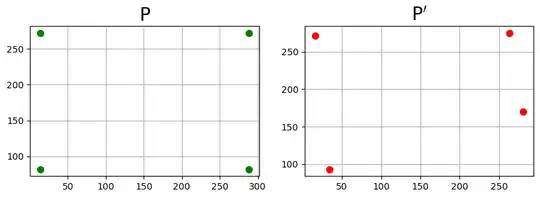

Now, let's demonstrate with python:

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pylab as plt

src = np.array([[14,28],

[288,28],

[14,218],

[288,218]])

dst = np.array([[34,207],

[281,130],

[16,29],

[263,25]])

x, y, u, v = src[:,0], src[:,1], dst[:,0], dst[:,1]

A = np.zeros((9,9))

j = 0

for i in range(4):

A[j,:] = np.array([-x[i], -y[i], -1, 0, 0, 0, x[i]u[i], y[i]u[i], u[i]])

A[j+1,:] = np.array([0, 0, 0, -x[i], -y[i], -1, x[i]v[i], y[i]v[i], v[i]])

j += 2

A[8, 8] = 1 # assuming h_9 = 1

b = [0]*8 + [1]

H = np.reshape(np.linalg.solve(A, b), (3,3))

print(H)

[[ 1.68471 , -0.09453488, 14.58392177],

[ 0.05006887, -0.97074686, 242.75163122],

[ 0.00264368, 0.00027783, 1. ]]

ps, p1s = [], []

for i in range(4):

p, q = src[i], dst[i]

p_hom = [p[0], p[1],1]

p1_hom = H@p_hom

p1 = [x / p1_hom[2] for x in p1_hom[:-1]]

ps.append(p)

p1s.append(p1)

print("P:{}, P':{}, H@P:{}".format(p, q, p1))

P:[14 28], P':[ 34 207], H@P:[34.0, 207.00000000000003]

P:[288 28], P':[281 130], H@P:[281.0, 130.0]

P:[ 14 218], P':[16 29], H@P:[16.0, 29.0]

P:[288 218], P':[263 25], H@P:[263.0, 24.999999999999986]

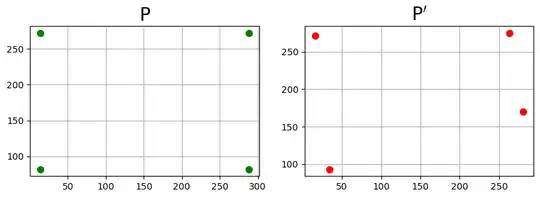

plot the original and transformed points

ps, p1s = np.array(ps), np.array(p1s)

max_y = 300

plt.figure(figsize=(10,3))

plt.subplot(121), plt.scatter(ps[:,0], max_y-ps[:,1], color='g', s=50), plt.title('P', size=20), plt.grid()

plt.subplot(122), plt.scatter(p1s[:,0], max_y-p1s[:,1], color='r', s=50), plt.title(r'P$^{\prime}$', size=20), plt.grid()

plt.show()

As can be seen, the transformed coordinates are same as the ground-truth ones (upto numerical precision) with the estimated homography matrix.

Reference: https://www.cs.cmu.edu/~16385/lectures/lecture9.pdf