Edit: I realized I have not addressed your actual question, which was concerend with the first criterion there, that the root vectors span the space $E$. You asked:

So does that mean that these root vectors have linear span or are something like a basis?

It cannot mean the first: Because remember that every (any) set of vectors span some vector space, namely their, well, span. So that would not be a condition at all.

It does not mean that the roots form a basis: Look at the example of the root system $A_2$ (six root vectors which point to the vertices of a perfect hexagon). They all lie in a plane of just two dimensions, so not all six vectors together are a basis.

What it literally means is that the root vectors are a generating system for their vector space $E$. They can fail to be a basis because they need not all be linearly independent. But they need to span their space (not just all lie in some lower-dimensional subspace).

Maybe it helps to see how this mild condition could possibly fail. Which of these examples a-g are root systems?

$a. \Phi = \{(1,0), (-1,0)\}, E= \mathbb R^2 \\

b. \Phi = \{(1,0), (-1,0)\}, E= \{ v=(v_1,v_2) \in \mathbb R^2: v_2 =0\}\\

c. \Phi = \{(1,0,-1),(-1,0,1),(1,-1,0),(-1,1,0),(0,1,-1),(0,-1,1)\}, E= \mathbb R^3 \\

d. \Phi= \{(1,0,-1),(-1,0,1),(1,-1,0),(-1,1,0),(0,1,-1),(0,-1,1)\}, E= \{v= (v_1,v_2, v_3) \in \mathbb R^3: v_1+v_2+v_3=0 \} \\

e. \Phi= \{(1,0),(-1,0),(-1/2,\sqrt3/2),(1/2,-\sqrt3/2),(1/2,\sqrt3/2)(-1/2,-\sqrt3/2)\}, E= \mathbb R^2 \\

f. \Phi = (0,-1.383,17,\sqrt\pi), (0,1.383,-17,-\sqrt \pi), E= \mathbb R^4 \\

g. \Phi = (0,-1.383,17,\sqrt\pi), (0,1.383,-17,-\sqrt \pi), E= span \langle(0,-1.383,17,\sqrt\pi)\rangle = \{(c,-1.383c,17c,\sqrt\pi c) \in \mathbb R^4: c \in \mathbb R\}$

Answer: a, c, and f are not because they fail criterion 1. In these examples, the space $E$ which we specified is "too big", it is not generated by the roots in $\Phi$ (in examples a and f, the roots in $\Phi$ span only a $1$-dimensional line and do not generate the spaces $E$ which are $2$- and $4$-dimensional, respectively; in example c, the span of $\Phi$ would be a two-dimensional plane, and does not span the entire vector space $E$ which has dimension $3$.

In all other examples, indeed $\Phi$ spans $E$ (and you will see that b,d, and g, are basically just "corrected" versions of a,c, and f, where we now chose $E$ "smaller" so that it is the span of $\Phi$). Example e is exactly the way you see the root system $A_2$ in the plane, note that here these vectors obviously do span the full $E= \mathbb R^2$.

Finally, we have not checked it yet, but indeed examples b, d, e, and g also satisfy all the other criteria, so indeed they are root systems. However, it should be very easy to see that a and g are actually "the same" (isomorphic). Indeed, they are two manifestations of the root system $A_1$ ; in a way, just different parametrizations of the same idea: It's just some non-zero vector and its negative, sitting in the line it spans.

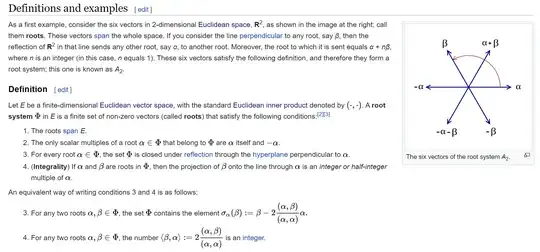

It is not quite that easy, but a very good exercise to see that examples d and e are also isomorphic to each other. They are different parametrizations (i.e. choice of underlying coordinates) of the root system $A_2$ which you see in the image there and which I will talk about in the rest of this answer. Think for yourself: In example e, which two of the roots could be $\alpha$ and $\beta$ in the picture? And what pairs of the six vectors in example d could be $\alpha$ and $\beta$?

A root system is just a bunch of vectors (best visualized in plain old Euclidean space) that has, in a sense made precise by the axioms, a lot of symmetry.

The basic one among these symmetries goes like this: Take any of the roots. Imagine the (hyper)plane which stands perpendicular on this root. Reflect everything at that hyperplane (i.e. use that plane as a mirror). Then all your roots have been reflected to another root, i.e. the whole thing thus reflected looks exactly as before.

Those six vectors which you see in the picture you uploaded are one example of a root system. See how their endpoints form a perfect hexagon. See how the angle between each root and its two neighbours on the left and right is exactly $60^°$. Imagine a coordinate system behind it, with the centre the origin, and all roots of length $1$.

Let's check those reflections: First, take the root called $\alpha$. What is the "hyperplane perpendicular to it"? We have just two dimensions in this example, so a plane is just a line; indeed, here it's just the vertical axis, which quite visibly is made up of everything that stands perpendicular to $\alpha$. OK, so let's reflect everything at that axis. What happens? Each of the roots finds its perfect mirror image: $\alpha$ switches with $-\alpha$, $\beta$ with $\alpha+\beta$, and $-\beta$ with $-\alpha-\beta$. Cool.

But what if instead, for example, we start with the root $\beta$. Then what is the

"hyperplane perpendicular to it"? Again it's just a line, but you have to imagine it, it is not drawn in the picture: It passes through the origin at an angle of $30^°$ above the root $\alpha$ on the horizontal axis, i.e. it cuts through exactly halfway between $\alpha$ and $\alpha+\beta$ in the first quadrant, and halfway between $-\alpha$ and $-\alpha-\beta$ in the third quadrant. OK, so let's use that one as mirror of the whole thing. What happens? Again, each root finds a perfect mirror image. This time, the reflection switches $\alpha \leftrightarrow \alpha +\beta$, $\beta \leftrightarrow -\beta$, and $-\alpha \leftrightarrow -\alpha-\beta$.

I leave it to you to imagine the reflection at the line perpendicular to the root $\alpha+\beta$.

Now in this root system, which as said in a way is a perfect hexagon, these things work. But now draw a proposed root sytem whose endpoints are a perfect pentagon. Try the reflections. You will see that some of them do not work: Some roots, when reflected, do not "land on" other roots. So those vectors (whose endpoints form a perfect pentagon) do not form a root system.

You should see that most other perfect $n$-gons do not work either! As a rare exception beside the hexagon, four vectors whose endpoints form a square do work; but, three vectors whose endpoints form a perfect triangle do not (when you try the reflections, you will see you have to "complete" the triangle to a hexagon like above).

Now beyond this basic one, there is a little more symmetry needed to make something a root system, which rules out even more vector sets even though on first sight they might look pretty symmetric.

For example, it turns out that in any root system, any two of the roots are only "allowed" to have either an angle of $0, 30, 45, 60, 90, 120, 135, 150$, or $180$ degrees between them. It also turns out that "many" of the roots have to have the same length. Etc. (In the above example, all roots have the same length, and you see that the possible angles between any two roots are only $0, 60, 120$, or $180$ degrees.)

This should be enough for a very coarse first idea. I advertise my related answers to How to visualize intuitively root systems and Weyl group?, and, already on an advanced level, Picture of Root System of $\mathfrak{sl}_{3}(\mathbb{C})$.

It's a whole different question why we are interested in root systems! The short answer to that is that if we know how to translate from them, they tell us a lot about the structure of certain groups and Lie algebras. However, this translation is quite involved and passes thorugh several levels of abstraction. One does not "get it" if one is not willing to cross-check a lot of things in examples and exercises involving many matrix computations. Some examples of this "translation" happen in my answers to Basic question regarding roots from a Lie algebra in $\mathbb{R}^2$ and Understanding an eigenspace of semi-simple elements in Lie algebra.