After discussion in the comments, I understand the question as follows: Say we have started with the Lie algebra $\mathfrak{sl}_3(K) = \lbrace A \in M_{3\times 3}(K): tr(A)=0 \rbrace$ and have chosen as the most obvious Cartan subalgebra the one consisting of the diagonal matrices in $\mathfrak{sl}_3(K)$ i.e.

$\mathfrak{h} = \lbrace \pmatrix{a&0&0\\0&b&0\\0&0&c}: a+b+c=0 \rbrace $,

as well as the roots $\pm\alpha, \pm \beta, \pm \gamma \in \mathfrak{h}^*$ given by

$\alpha(\pmatrix{a&0&0\\0&b&0\\0&0&c})= a-b$,

$\beta(\pmatrix{a&0&0\\0&b&0\\0&0&c})= b-c$,

$\gamma(\pmatrix{a&0&0\\0&b&0\\0&0&c})= a-c$.

We might also have found the corresponding root spaces $\mathfrak{g}_\alpha = \pmatrix{0&*&0\\0&0&0\\0&0&0}$ to $\alpha$, $\mathfrak{g}_{-\alpha} = \pmatrix{0&0&0\\*&0&0\\0&0&0}$ to $-\alpha$, $\mathfrak{g}_{\alpha+\beta} =\pmatrix{0&0&*\\0&0&0\\0&0&0}$ to $\alpha+\beta$ etc. (We can call $\pmatrix{0&1&0\\0&0&0\\0&0&0}$ a "root vector" to the root $\alpha$, but so is $\pmatrix{0&17&0\\0&0&0\\0&0&0}$.)

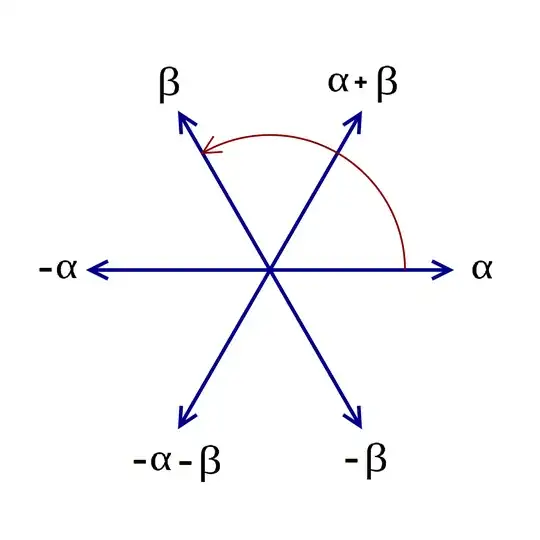

Now the question is: How do we get, from this, that the root system looks like the picture in the OP?

A shortcut is to to notice that $\gamma=\alpha+\beta$ and to use the classification of root systems, which tells us that the only root system which consists of six roots, three of which positive, one of which is the sum of the other two, is the root system $A_2$, and ten thousand people before us have checked that that root system looks as the picture in the OP.

The more rewarding way is as follows: A full description of a root system and its "geometry" needs the coroots $\check{\alpha}, \check{\beta} ...$ to the roots. Namely, the crucial relations are

$s_{\alpha}(\beta) = \beta-\check{\alpha}(\beta) \beta$ (reflection of $\beta$ at the hyperplane perpendicular to $\alpha$), and more or less equivalently

$(\ast) \qquad \check{\alpha}(\beta) \cdot \check{\beta}(\alpha) = 4 \cos^2(\theta)$ where $\theta$ is the angle between $\alpha$ and $\beta$.

With these formulae we get the "realisation" of our root system in an Euclidean space, as soon as we have those coroots. One obvious property we need is $\check{\rho}(\rho) = 2$ for all roots, but where are those coroots in the Lie algebra? They are realised as special elements of $\mathfrak{h}^{**} \simeq \mathfrak{h}$, as follows: For each root $\rho$, the space $[\mathfrak{g}_\rho, \mathfrak{g}_{-\rho}]$ is a one-dimensional subspace of $\mathfrak{h}$, and it contains a

unique element $H_{\rho} \in [\mathfrak{g}_\rho, \mathfrak{g}_{-\rho}]$ such that $\rho(H_\rho) =2$.

This element $H_\rho \in \mathfrak{h}$ is the coroot $\check{\rho}$ via the identification $\mathfrak{h}^{**} \simeq \mathfrak{h}$. (Down to earth: For each root $\sigma$, $\check{\rho}(\sigma) = \sigma(H_{\rho})$.)

In our example, we get

$[\mathfrak{g}_\alpha, \mathfrak{g}_{-\alpha}] = \lbrace \pmatrix{a&0&0\\0&-a&0\\0&0&0} : a \in K \rbrace$ and hence $H_\alpha = \pmatrix{1&0&0\\0&-1&0\\0&0&0}$, and likewise

$H_\beta= \pmatrix{0&0&0\\0&1&0\\0&0&-1}$, $H_\gamma= \pmatrix{1&0&0\\0&0&0\\0&0&-1}$, $H_{-\alpha} = \pmatrix{-1&0&0\\0&1&0\\0&0&0}$ etc.

In particular, $\check{\alpha}(\beta) = \beta(H_\alpha) = -1$ as well as $\check{\beta}(\alpha) = \alpha(H_\beta)=-1$ which together with $(\ast)$ tells us that the angle between $\alpha$ and $\beta$ has cosine $1/2$ or $-1/2$, i.e. is either $60°$ or $120°$. Checking the other combinations quickly shows that it must actually be $120°$, that $\alpha+\beta$ sits exactly "between" $\alpha$ and $\beta$ with and angle of $60°$ to each, and consequently that the root system looks as in the picture.

Added in response to comment: Be aware that $\rho(H_\rho) = 2$ is true by definition for all $\rho$, regardless of the length of $\rho$. Rather, the ratio of two root lengths is given by

$$\dfrac{\lvert \lvert \beta \rvert \rvert^2}{\lvert \lvert \alpha\rvert \rvert^2} = \dfrac{\beta(H_\alpha)}{\alpha(H_\beta)}$$

(and, as is well known, can only take the values $3,2,1,\frac12, \frac13$).

[In many sources they write something like $\langle \beta, \check{\alpha} \rangle$ for $\beta(H_\alpha)= \check{\alpha}(\beta)$ but it is important to note that this $\langle, \rangle$ is not a scalar product (it's generally not even symmetric to begin with) and thus will not directly give us lengths. "True" scalar products are then usually denoted by something like $(\alpha \vert \beta)$, and that would give the above $\lvert \lvert \alpha \rvert \rvert^2 = (\alpha \vert \alpha)$.]

Note further that it is in general not true that $H_{\alpha+\beta} \stackrel{?}= H_\alpha + H_\beta$ (in fancier words and more precisely: the map $\rho \mapsto H_\rho$ is in general not a morphism, let alone isomorphism, of root systems $\Phi \rightarrow \check{\Phi}$). To see a concrete example, look at a form of type $B_2$, i.e. (compare https://math.stackexchange.com/a/3629615/96384, where the matrices are mirrored at the diagonal, and the notation for $\alpha$ and $\beta$ is switched)

$\mathfrak{so}_5(\mathbb C) := \lbrace \pmatrix{a&b&0&e&g\\

c&d&-e&0&h\\

0&f&-a&-c&i\\

-f&0&-b&-d&j\\

-i&-j&-g&-h&0\\} : a, ..., j \in \mathbb C \rbrace$.

Exercise: There is a long root $\beta$ and a short root $\alpha$ such that a system of simple roots is given by $\beta, \beta+\alpha, \beta+2\alpha, \alpha$, and we have

$$H_\beta = \pmatrix{1&0&0&0&0\\

0&-1&0&0&0\\

0&0&-1&0&0\\

0&0&0&1&0\\

0&0&0&0&0\\}, H_\alpha= \pmatrix{0&0&0&0&0\\

0&2&0&0&0\\

0&0&0&0&0\\

0&0&0&-2&0\\

0&0&0&0&0\\},$$

but

$$H_{\alpha+\beta} = \pmatrix{2&0&0&0&0\\

0&0&0&0&0\\

0&0&-2&0&0\\

0&0&0&0&0\\

0&0&0&0&0\\} \neq H_\alpha +H_\beta.$$

Note that as said $\rho(H_\rho)=2$ for all roots, so we cannot tell long from short roots with that; but $\beta(H_\alpha) = -2, \alpha(H_\beta)=-1$ which makes $\beta$ longer than $\alpha$ by a factor of $\sqrt2$, and with the method from above, we get that the angle between $\alpha$ and $\beta$ is $3\pi/4 \hat{=} 135°$, and the root system looks like this: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Root_system_B2.svg