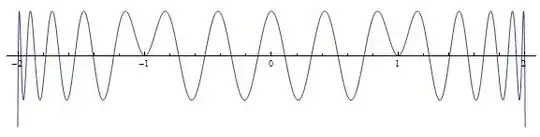

I'd like to be able to construct polynomials $p$ whose graphs look like this:

We can assume that the interval of interest is $[-1, 1]$. The requirements on $p$ are:

(1) Equi-oscillation (or roughly equal, anyway) between two extremes. A variation of 10% or so in the values of the extrema would be OK.

(2) Zero values and derivatives at the ends of the interval, i.e. $p(-1) = p(1) =p'(-1) = p'(1) = 0$

I want to do this for degrees up to around 30 or so. Just even degrees would be OK.

If it helps, these things are a bit like Chebyshev polynomials (but different at the ends).

The one in the picture has equation $0.00086992073067855669451 - 0.056750328789339152999 t^2 + 0.60002383910750621904 t^4 - 2.3217878459074773378 t^6 + 4.0661558859963998471 t^8 - 3.288511471137768132 t^{10} + t^{12}$

I got this through brute-force numerical methods (solving a system of non-linear equations, after first doing a lot of work to find good starting points for iteration). I'm looking for an approach that's more intelligent and easier to implement in code.

Here is one idea that might work. Suppose we want a polynomial of degree $n$. Start with the Chebyshev polynomial $T_{n-2}(x)$. Let $Q(x) = T_{n-2}(sx)$, where the scale factor $s$ is chosen so that $Q(-1) = Q(1) = 0$. Then let $R(x) = (1-x^2)Q(x)$. This satisfies all the requirements except that its oscillations are too uneven -- they're very small near $\pm1$ and too large near zero. Redistribute the roots of $R$ a bit (somehow??) to level out the oscillations.

Comments on answers

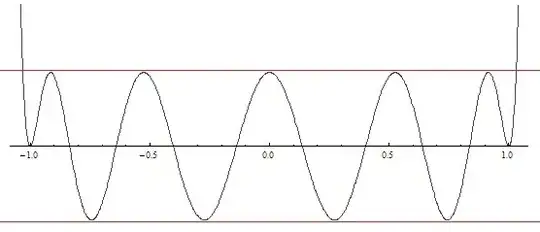

Using the technique suggested by achille hui in an answer below, we can very easily construct a polynomial with the desired shape. Here is one:

The only problem is that I was hoping for a polynomial of degree 12, and this one has degree 30.

Also, I was expecting the solution to grow monotonically outside the interval $[-1,1]$, and this one doesn't, as you can see here: