The OP asks:

What am I doing wrong with this method?

When should I not use polar coordinates to find limits of multivariable functions?

The answer to the second question is somewhat unsatisfactory: If you find a limit, then you can. If you don't find a limit, then you can't.

So now, let's just leave that behind us and focus on the first question: "What am I doing wrong with this method?"

For this I will just consider the case where we have cartesian coordinates. The analogy with polar coordinates should be evident.

The mistake you made actually has nothing to do with "polar coordinates" per se, but with "limits". To this end, I'll first repeat the definition of the limit of a two-variable function here:

Suppose we have a function

\begin{align}f:\mathbb R\times \mathbb R\supset U&\to \mathbb R\\

(x,y)&\mapsto f(x,y)\end{align}

For a point $(a,b)\in\mathbb R$ we say that $\lim\limits_{(x,y)\to (a,b)}f(x,y)=L$, if and only if,

$$\forall \varepsilon>0\,\exists \delta >0: \big(\Vert (x,y)-(a,b)\Vert<\delta \implies \vert f(x,y)-L\vert<\epsilon\big).\tag{*}$$

In words $(*)$ says that $f(x,y)$ will be close to $L$, whenever the point $(x,y)$ is sufficiently close to the point $(a,b)$.

Now comes your mistake: We have not defined what $\lim\limits_{x\to a}f(x,y)$ should mean. To say something about the limt of $f(x,y)$ we need to manipulate points in $\mathbb R^2$. But $x\to a$ means we are considering points in $\mathbb R$ which lie close to $a$ (which is definitely not a point in $\mathbb R^2$).

So this is a problem. If we would want to evaluate $\lim\limits_{x\to a}f(x,y)$, we would first have to define what this means. So let's do that:

Define $\ell_a\subset \mathbb R^2$ as the line $x=a$, i.e. $\ell_a =\left\{(x,y)\in\mathbb R^2\mid x=a\right\}$. Also introduce the notation: $d\big(\ell_a,(x,y)\big)=\text{distance between $(x,y)$ and $\ell_a$}$.

Now we say that $\lim\limits_{x\to a}f(x,y)=L(y)$, if and only if,

$$\forall\varepsilon>0\,\exists\delta>0: \Big(d\big(\ell_a,(x,y)\big)\tag{**}<\delta \implies\vert f(x,y)-L(y)\vert<\varepsilon\Big).$$

In words $(**)$ says that $f(x,y)$ will be close to $L$, whenever the point $(x,y)$ is sufficiently close to the line $x=a$.

Notice the difference of the definitions in $(*)$ and $(**)$. The first tells us what happens if we are close to some point, the second tells us what happens if we are close to some line. Also, $(**)$ only says that we can get close to $L(y)$, which is some funtion of $y$. In general, proving that $\lim\limits_{x\to a}f(x,y)=L(y)$ is not at all easy and quite often not usesful.

To sum up: The problem is that $\lim\limits_{r\to 0}\frac{r\cos^2\theta\sin\theta}{r^2\cos^4\theta+\sin^2\theta}$ is actually a rather stange and unuseful thing. If ever, it needs to be used with caution. This in particular means that it cannot be evaluated by simply substituting $r$ by $0$.

As an extra I would like to leave you with a funtion $f(r,\theta)$ for which $\lim\limits_{r\to 0}f(r,\theta)$ is of more use:

$$\lim_{r\to 0}\frac {r\cos^2\theta \sin\theta}{r^2\cos^4\theta +1}=0\text{, because}$$

$$0<r<\delta\implies \left\vert\frac {r\cos^2\theta \sin\theta}{r^2\cos^4\theta +1}\right\vert<\left\vert\frac {r\cos^2\theta \sin\theta}{1}\right\vert=r\left\vert \cos^2\theta\sin\theta\right\vert<\delta\underbrace{\left\vert \cos^2\theta\sin\theta\right\vert}_{\text{bounded}}.\\\text{The singular cases where $\cos^2\theta \sin\theta=0$ are easily seen to be compatible.}$$

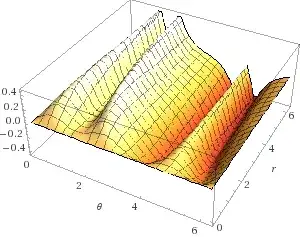

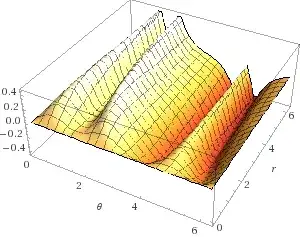

This rimes with its graph: