The function

$$f(x)=|\text{sinc}(x)|\tag{1}$$

can be evaluated as

$$f(x)=g_1(x)\, h_1(x)\tag{2}$$

where

$$g_1(x)=\left|\frac{1}{x}\right|\tag{3}$$

and

$$h_1(x)=|\sin(x)|\tag{4}$$

Therefore the Fourier transform

$$\hat{f}(\omega)=\mathcal{F}_x[f(x)](\omega)=\int\limits_{-\infty}^{\infty} f(x)\, e^{-2 \pi i \omega x} \, dx\tag{5}$$

can be evaluated as the convolution

$$[\hat{g}_1(\xi) * \hat{h}_1(\xi)](\omega)=\int\limits_{\infty}^{\infty} \hat{g}_1(\xi)\, \hat{h}_1(\omega-\xi) \, d\xi\tag{6}$$

where

$$\hat{g}_1(\omega)=\mathcal{F}_x[g_1(x)](\omega)=-2 (\log(2 \pi |\omega|)+\gamma)\tag{7}$$

is the Fourier transform of $g_1(x)$ and $\hat{h}_1(\omega)=\mathcal{F}_x[h_1(x)](\omega)$ is the Fourier transform of $h_1(x)$.

The function $h_1(x)$ is a $\pi$-periodic function with Fourier series

$$h_1(x)=\frac{2}{\pi}+\frac{4}{\pi} \lim\limits_{N\to\infty} \left(\sum\limits_{n=1}^N \frac{1}{1-4 n^2}\, \cos(2 n x)\right)\tag{8}$$

and the term-wise Fourier transform of formula (8) above is

$$\hat{h}_1(\omega)=\frac{2}{\pi}\, \delta(\omega)+\frac{4}{\pi} \lim\limits_{N\to\infty} \left(\sum\limits_{n=1}^N \frac{1}{1-4 n^2}\, \left(\frac{1}{2}\, \delta\left(\omega+\frac{n}{\pi}\right)+\frac{1}{2}\, \delta\left(\omega-\frac{n}{\pi}\right)\right)\right)\tag{9}$$

which when convolved term-wise with $\hat{g}_1(\omega)$ leads to the series representation

$$\hat{f}(\omega)=-\frac{4}{\pi}\, (\gamma+\log(2 \pi |\omega|))\\+\frac{4}{\pi}\, \lim\limits_{N\to\infty} \left(\sum\limits_{n=1}^N \frac{1}{4 n^2-1}\, \left(2 \gamma-\log\left(\frac{1}{4 \left| n^2-\pi^2 \omega^2\right|}\right)\right)\right)\\=-\frac{4}{\pi}\, \log(\pi |\omega|)+\frac{4}{\pi} \lim\limits_{N\to\infty} \left(\sum\limits_{n=1}^N \frac{\log\left(\left| n^2-\pi^2 \omega^2\right| \right)}{4 n^2-1}\right)\tag{10}.$$

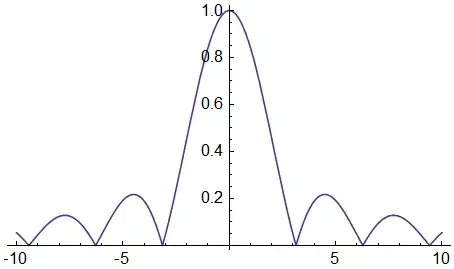

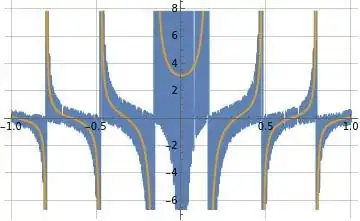

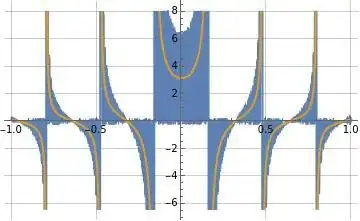

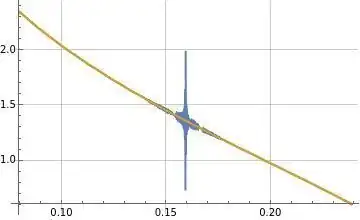

Figure (1) below illustrates formula (10) above for $\hat{f}(\omega)$ evaluated at $N=1000$. Note formula (10) above for $\hat{f}(\omega)$ seems to evaluate consistent with the plots of the Fourier transform in the accepted answer posted by robjohn.

Figure (1): Illustration of formula (10) for $\hat{f}(\omega)$

The inverse Fourier transform of formula (10) above leads to the series representation

$$f(x)=\frac{4 (\gamma+\log(2))}{\pi }\, \delta(x)+\frac{2}{\pi |x|}-\frac{4}{\pi |x|} \lim\limits_{N\to\infty} \left(\sum\limits_{n=1}^N \frac{\cos(2 n x)}{4 n^2-1}\right)\tag{11}$$

which interestingly simplifies to the following alternate closed-form representation of $f(x)=|\text{sinc}(x)|$.

$$f(x)=\frac{4 (\gamma+\log (2))}{\pi}\, \delta(x)+\frac{2 i \sin(x) \left(\coth^{-1}\left(e^{i x}\right)-\tanh^{-1}\left(e^{i x}\right)\right)}{\pi | x|}\tag{12}$$

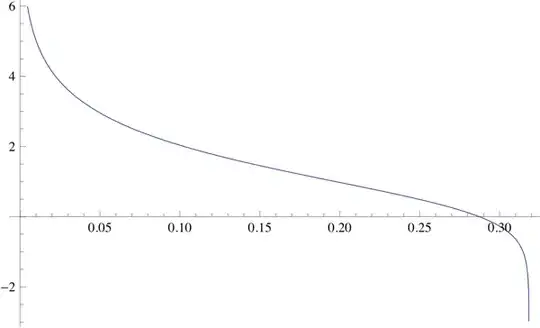

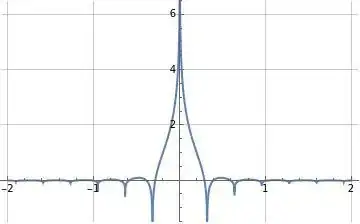

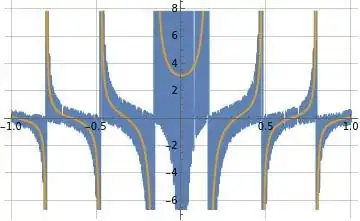

Figure (2) below illustrates the series representation in formula (11) above evaluated at $N=1000$ seems to converge very well to $f(x)=|\text{sinc}(x)|$.

Figure (2): Illustration of series representation in formula (11) for $f(x)=|\text{sinc}(x)|$ in orange overlaid on $|\text{sinc}(x)|$ in blue

As was pointed out in the accepted answer posted by robjohn, the function $f(x)=|\text{sinc}(x)|$ can also be evaluated as

$$f(x)=g_2(x)\, h_2(x)\tag{13}$$

where

$$g_2(x)=\text{sinc}(x)\tag{14}$$

and

$$h_2(x)=\text{sgn}(\text{sinc}(x))\tag{15}$$

Therefore the Fourier transform

$$\hat{f}(\omega)=\mathcal{F}_x[f(x)](\omega)=\int\limits_{-\infty}^{\infty} f(x)\, e^{-2 \pi i \omega x} \, dx\tag{16}$$

can be evaluated as the convolution

$$[\hat{g}_2(\xi) * \hat{h}_2(\xi)](\omega)=\int\limits_{\infty}^{\infty} \hat{g}_2(\xi)\, \hat{h}_2(\omega-\xi) \, d\xi\tag{17}$$

where

$$\hat{g}_2(\omega)=\mathcal{F}_x[g_2(x)](\omega)=\frac{\pi}{2} (\text{sgn}(1+2 \pi \omega)+\text{sgn}(1-2 \pi \omega))\tag{18}$$

corresponding to a rectangle function of height $\pi$ and width $\frac{1}{\pi}$ is the Fourier transform of $g_2(x)$ and

$$\hat{h}_2(\omega)=\mathcal{F}_x[h_2(x)](\omega)=\frac{\tan\left(\pi^2 \omega\right)}{\pi \omega}\tag{19}$$

is the Fourier transform of $h_2(x)$.

The accepted answer posted by robjohn gives a couple of series representations of $\hat{h}_2(\omega)$ the first of which is

$$\hat{h}_2(\omega)=\lim\limits_{K\to\infty} \left(\sum\limits_{k=0}^K (-1)^k\, \frac{\sin\left(2 \pi^2 (k+1) \omega\right)-\sin\left(2 \pi^2 k \omega\right)}{\pi \omega}\right)\tag{20}$$

but the second one should actually be

$$\hat{h}_2(\omega)=\frac{2}{\pi \omega} \lim\limits_{K\to\infty} \left(\sum\limits_{k=0}^K (-1)^k\, \sin\left(2 \pi^2 (k+1) \omega\right)\right)-\delta(\omega)\tag{21}$$

because there's a subtle inconsistency as the inverse Fourier transform of formula (20) above evaluates to $\text{sgn}(\text{sinc}(x))$ whereas the inverse Fourier transform of the series portion of formula (21) above evaluates to $\text{sgn}(\text{sinc}(x))+1$, and consequently formula (21) has been adjusted to include a $-\delta(\omega)$ correction term.

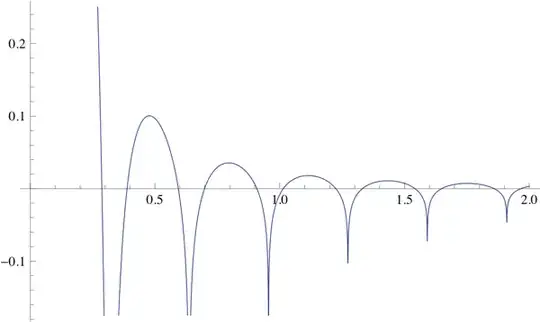

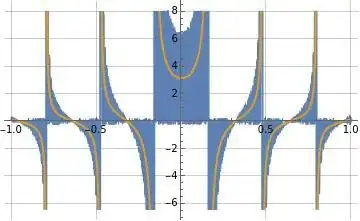

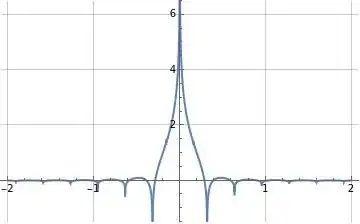

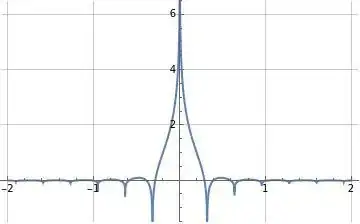

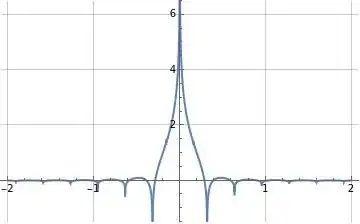

Figures (3) and (4) below illustrate formulas (20) and (21) don't converge in the usual sense, i.e. they only converge in a distributional sense in integrals such as their related inverse Fourier transform and convolution integrals.

Figure (3): Illustration of formula (20) for $\hat{h}_2(\omega)$ evaluated at $N=1000$ in blue overlaid by the reference function $\hat{h}_2(\omega)=\frac{\tan\left(\pi^2 \omega\right)}{\pi \omega}$ in orange

Figure (4): Illustration of formula (21) for $\hat{h}_2(\omega)$ evaluated at $N=1000$ in blue overlaid by the reference function $\hat{h}_2(\omega)=\frac{\tan\left(\pi^2 \omega\right)}{\pi \omega}$ in orange

Formulas (20) and (21) above convolved term-wise with $\hat{g}_2(\omega)$ lead to the formulas

$$\hat{f}(\omega)=\lim\limits_{K\to\infty} \left(\sum\limits_{k=0}^K (-1)^k (\text{Si}(\pi (k+1) (2 \pi \omega+1))-\text{Si}(k \pi (2 \pi \omega+1))\\+\text{Si}(\pi (k+1) (1-2 \pi \omega))-\text{Si}(k \pi (1-2 \pi \omega)))\right)\tag{22}$$

and

$$\hat{f}(\omega)=\lim\limits_{K\to\infty} \left(2 \sum\limits_{k=0}^K (-1)^k (\text{Si}(\pi (k+1) (2 \pi \omega+1))+\text{Si}(\pi (k+1) (1-2 \pi \omega)))\right)\\-\hat{g}_2(\omega)\tag{23}$$

for $\hat{f}(\omega)$ where $\hat{g}_2(\omega)$ in formula (23) above corresponds to the rectangle function defined in formula (18) above.

Figures (5) and (6) below illustrate formulas (22) and (23) for $\hat{f}(\omega)$ above seem to evaluate similar to formula (10) for $\hat{f}(\omega)$ above (see Figure (1) above), but note formula (23) above illustrated in Figure (6) below doesn't seem to converge as well near $\omega=\pm\frac{1}{2 \pi}$ where the correction term $-\hat{g}_2(\omega)$ takes a step.

Figure (5): Illustration of formula (22) for $\hat{f}(\omega)$ evaluated at $K=1000$

Figure (6): Illustration of formula (23) for $\hat{f}(\omega)$ evaluated at $K=1000$

Substituting analytic representations for $\delta(x)$ in formula (21) above and $\hat{g}_2(\omega)$ in formula (23) above leads to

$$\hat{h}_2(\omega)=\frac{2}{\pi \omega} \lim\limits_{K\to\infty} \left(\sum\limits_{k=0}^K (-1)^k\, \sin\left(2 \pi^2 (k+1) \omega\right)\\-\frac{1}{2} \sin\left(2 \pi^2 (K+1) \omega\right)\right)\tag{24}$$

and

$$\hat{f}(\omega)=\lim\limits_{K\to\infty} \left(2 \sum\limits_{k=0}^K (-1)^k (\text{Si}(\pi (k+1) (2 \pi \omega+1))+\text{Si}(\pi (k+1) (1-2 \pi \omega)))\\-\text{Si}(\pi (K+1) (2 \pi \omega+1))+\text{Si}(\pi (K+1) (2 \pi \omega-1))\right)\tag{25}.$$

Formula (24) above seems to evaluate more similar to formula (20) illustrated in Figure (3) above than formula (21) illustrated in Figure (4) above.

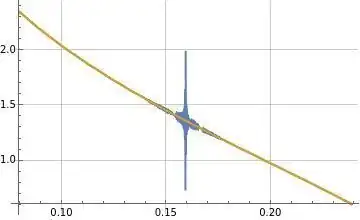

Formula (25) seems to converge near $\omega=\pm\frac{1}{2 \pi}$ more similar to formulas (10) and (22) above than formula (23) above. Figure (7) below illustrates formula (25) above in orange overlaid on formula (23) above in blue where both formulas are evaluated at $N=1000$.

Figure (7): Illustration of formulas (23) and (25) for $\hat{f}(\omega)$ in blue and orange respectively

Also I believe the formula

$$\hat{f}(\omega)=\mathcal{F}_x[|\text{sinc}(x)|](\omega)=\frac{2}{\pi} \lim\limits_{N\to\infty} \left(\sum\limits_{n=1}^N \frac{\log\left(\left|\frac{\pi^2 \omega^2-n^2}{\pi^2 \omega^2-(n-1)^2}\right|\right)}{2 n-1}\right)\tag{26}$$

evaluates similar to formulas (10), (22), and (25) above. Formula (26) above was derived from the relationship

$$|\text{sinc}(x)|=\text{sgn}(x)\, \text{sinc}(x)\, r(x)\tag{27}$$

where

$$r(x)=\left\{\begin{array}{cc}

1 & 0\leq x<\pi \\

-1 & \pi \leq x<2 \pi \\

r(x \bmod (2 \pi )) & \text{Otherwise} \\

\end{array}\right.\tag{28}$$

is a $2 \pi$ periodic rectangle wave with Fourier series

$$r(x)=\frac{4}{\pi} \lim\limits_{N\to\infty} \left(\sum\limits_{n=1}^N \frac{\sin((2 n-1) x)}{2 n-1}\right)\tag{29}.$$