This problem originates from another question, which was closed for lack of context. I found a solution but some details are still missing, as explained below.

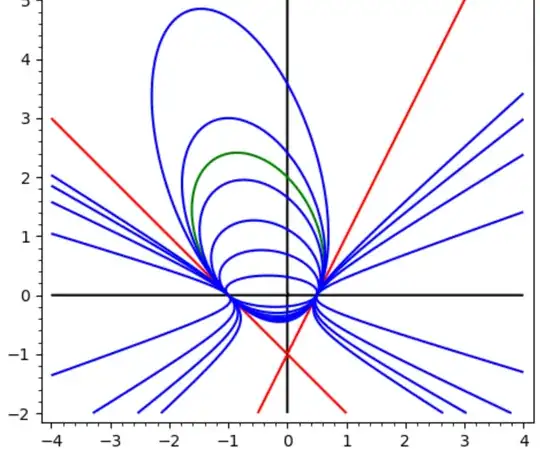

Given an angle and a point $P$ inside it, consider all chords $$ such that $\angle =90°$. Show that the envelope of those chords is a conic section.

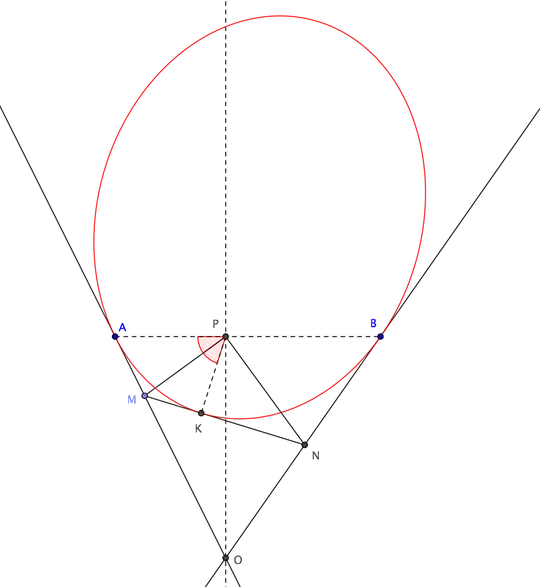

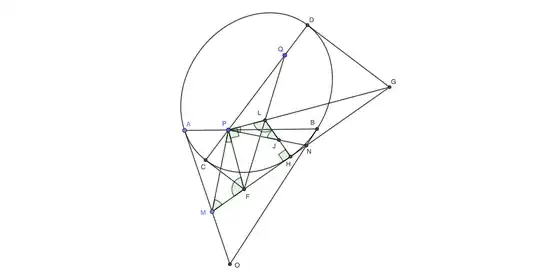

Let $A$, $B$ be the intersections of the sides with the perpendicular to $OP$ at $P$, where $O$ is the vertex of the angle (see figure below) and consider points $M$, $N$ on $OA$, $OB$ such that $\angle MPN=90°$.

Suppose I managed to show that the tangency point $K$ between line $MN$ and the envelope is such that $\angle MPK=\angle APM$. If so we immediately get that the envelope is a conic, tangent to the given lines at $A$, $B$ and having $P$ as focus. This follows from a nice theorem (see here for a proof):

If two tangents are drawn to a conic from an external point, then they subtend equal angles at the focus.

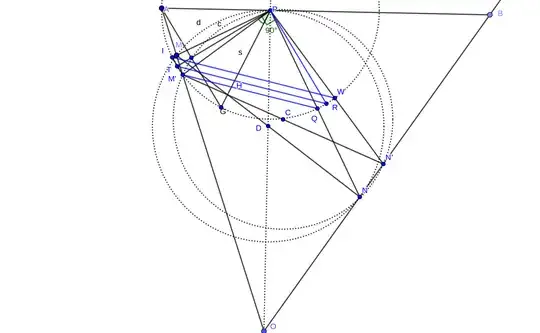

Note that the conic is uniquely defined from its tangencies at $A$, $B$ and its focus at $P$. Moreover, point $O$ lies on the directrix relative to focus $P$ and the type of conic section depends on $\angle AOB$:

it is an ellipse if $\angle AOB<90°$;

it is a parabola if $\angle AOB=90°$;

it is a hyperbola if $\angle AOB>90°$.

EDIT.

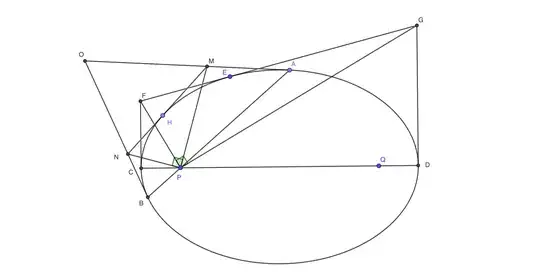

From the above theorem we obtain as a corollary that:

If from the endpoints of a focal chord $APB$ tangents $OA$, $OB$ are drawn, and a third tangent at $K$ cuts $OA$, $OB$ at $M$ and $N$ respectively, then $\angle MPN=90°$.

Proof: we have $\angle APM=\angle MPK$ and $\angle KPN=\angle NPB$, hence:

$$ \angle MPN=\angle MPK+\angle KPN= {1\over2}(\angle APK+\angle KPB)={1\over2}\cdot 180°. $$

As observed by Edward Porcella in his answer, the desired property is just the converse of this corollary and can be proved by RAA: construct the unique conic section with focus $P$ and tangents $OA$, $OB$, then consider a chord $$ of $\angle AOB$ such that $\angle =90°$. If $MN$ were not tangent to the ellipse we could construct a tangent $M'N'$ to the ellipse, parallel to $MN$. But then $\angle MPN=90°=\angle M'PN'$, which is impossible.

This neat proof is simpler and doesn't require proving $\angle MPK=\angle APM$. Nevertheless, I'd like to find a simple proof of the property shown below.

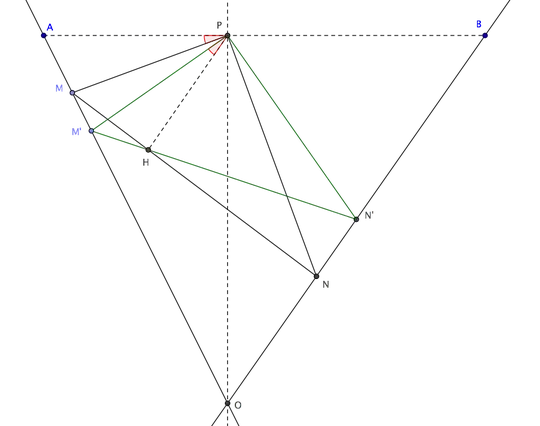

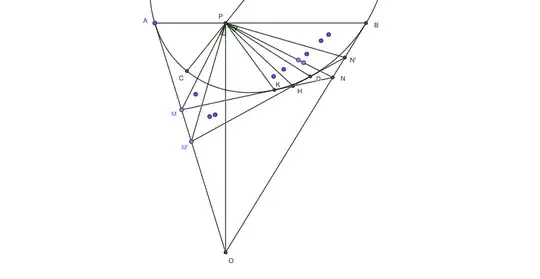

Consider a second chord $M'N'$ of $\angle AOB$, such that $\angle M'PN'=90°$, intersecting $MN$ at $H$ (see figure below). Tangency point $K$ is then the limiting position of $H$ as $M'\to M$.

Experimenting with GeoGebra, I found that $\angle M'PH=\angle APM$ for any position of $M'$. If so, in the limit $M'\to M$ we have $\angle M'PH\to \angle MPK=\angle APM$ as it was to be proved. But I cannot prove that $\angle M'PH=\angle APM$: it should be an easy geometric result, but it somehow eludes me. How to show that?