I have read this theorem in my book but i do not know how to prove it.

If a family of straight lines can be represented by an equation $\lambda^2 P+\lambda Q+R=0$ where $\lambda $ is a parameter and $P,Q,R$ are linear functions of $x$ and $y$ then the family of lines will be tangent to the curve $Q^2=4PR.$

My try:

Let $P:a_1x+b_1y+c_1=0$

$Q:a_2x+b_2y+c_2=0$

$R:a_3x+b_3y+c_3=0$

Then the family of straight lines can be represented by an equation $\lambda^2 (a_1x+b_1y+c_1)+\lambda (a_2x+b_2y+c_2)+(a_3x+b_3y+c_3)=0$

$x(\lambda^2a_1+\lambda a_2+a_3)+y(\lambda^2b_1+\lambda b_2+b_3)+(\lambda^2c_1+\lambda c_2+c_3)=0$

But i do not know how to prove that the family of lines will be tangent to the curve $Q^2=4PR.$

- 88,997

- 4,512

-

1Surely there is some way to exploit the fact that the curve $Q^2 = 4 P R$ is the zero level set of the discriminant (in $\lambda$) of the polynomial $\lambda^2 P + \lambda Q + R$ defining the family. – Travis Willse Mar 11 '16 at 15:06

-

Great question (+1) That makes me wonder how anyone comes up with a question like that in the first place :) – imranfat Mar 11 '16 at 16:10

4 Answers

You are seeking the envelope of the family of lines. As described in the Wikipedia entry, there is a standard approach to this task, using Calculus.

Write $$F(\lambda) \;=\; \lambda^2 P + \lambda Q + R$$ so that differentiating with respect to $\lambda$ yields $$F^\prime(\lambda) \;=\; 2\lambda P + Q$$

Then simply eliminate $\lambda$ from the equations $F(\lambda) = 0$ and $F^\prime(\lambda) = 0$. Solving the second equation gives $\lambda = -\frac{Q}{2P}$; substituting into the first equation gives, after a little algebraic manipulation, $$Q^2 = 4 PR$$ as desired. $\square$

- 83,939

-

Particular case : if $P,Q,R$ are first degree polynomials, this equation $Q^2-4PR=0$ is in general a second degree polynomial corresponding to a conic curve. See for example here. – Jean Marie Mar 14 '25 at 18:26

-

1I just wrote a (modest!) answer here connecting this issue with quadratic equations representations using a (S,P) plane, where $S,P$ are resp. the sum and product of the roots. – Jean Marie Apr 02 '25 at 15:01

This is a pretty brute-force method but it works.

Test

To figure out what was going on, I tried a simple case: $P=x$, $Q=y$, $R=1$. The family of lines is $$\lambda^2x +\lambda y + 1 = 0$$ and the quadratic is $$y^2 = 4x$$ To say that the family of lines is tangent to the curve means that wherever they intersect, their derivatives agree.

So first, we look at the intersections. If $\lambda^2 x + \lambda y + 1 = 0$, then $y = -\lambda x -\frac{1}{\lambda}$ ($\lambda \neq 0$ because then the line's equation becomes $1=0$). So $y^2 = \lambda^2 x^2 + 2x + \frac{1}{\lambda^2}$. On the other hand, if $y^2 = 4x$, then \begin{align*} \lambda^2 x^2 + 2x + \frac{1}{\lambda^2} &= 4x \\ \implies \lambda^2 x^2 - 2x + \frac{1}{\lambda^2} &= 0 \\ \implies \left(\lambda x - \frac{1}{\lambda}\right)^2 &= 0\\ \implies x &= \frac{1}{\lambda^2} \end{align*} If follows that $y = -\lambda \cdot \frac{1}{\lambda^2} - \frac{1}{\lambda} = -\frac{2}{\lambda}$. This jibes with the second equation $y^2 = 4x$.

The derivative $\frac{dy}{dx}$ along the line $\lambda^2 x + \lambda y + 1 = 0$ is clearly the slope $-\lambda$. The derivative along the curve $y^2=4x$ is $$ 2y \frac{dy}{dx} = 4\implies \frac{dy}{dx} = \frac{2}{y} $$ If $y=-\frac{2}{\lambda}$ then $\frac{2}{y} = -\lambda$, as desired.

The general case

Now I'm going to be careful not to divide by zero. Let $F = \lambda^2 P + \lambda Q + R$ and $G = Q^2-4PR$. We want to show $$ \begin{vmatrix} F_x & F_y \\ G_x & G_y \end{vmatrix} =0 $$ at the intersections $F=G=0$.

First, we reduce the equations for the intersections. If $\lambda^2 P + \lambda Q + R = 0$, then $\lambda Q = - \lambda^2 P - R$, so $$ \lambda^2 Q^2 = \lambda^4 P^2 + 2\lambda^2 PR + R^2 $$ On the other hand, if $Q^2 =4PR$, then $\lambda^2 Q^2 = 4\lambda PR$, and we have \begin{align*} \lambda^4 P^2 + 2\lambda^2 PR + R^2 &= 4\lambda PR \\ \implies \lambda^4 P^2 - 2\lambda^2 PR + R^2 &= 0 \\ \implies \left(\lambda^2 P-R\right)^2 &=0 \\ \implies \lambda^2 P-R &=0 \tag{1}\\ \end{align*} Substituting $R=\lambda ^2P$ into the first equation gives $$ 2\lambda^2 P + \lambda Q = 0 \implies \lambda(2\lambda P + Q) = 0 \implies 2\lambda P + Q=0 \tag{2} $$

Now we compute the determinant of the derivatives: $$ \begin{vmatrix} F_x & F_y \\ G_x & G_y \end{vmatrix} = \begin{vmatrix} \lambda^2 P_x + \lambda Q_x + R_x & \lambda^2 P_y + \lambda Q_y + R_y \\ 2QQ_x - 4P_xR - 4PR_x & 2QQ_y - 4P_yR - 4PR_y \\ \end{vmatrix} $$ Add $4P$ times the first line to the second line. The determinant is $$ \begin{vmatrix} \lambda^2 P_x + \lambda Q_x + R_x & \lambda^2 P_y + \lambda Q_y + R_y \\ 2(2\lambda P+Q)Q_x +4(\lambda^2P- R)P_x & 2(2\lambda P+Q)Q_y +4(\lambda^2P- R)P_y \end{vmatrix} $$ In light of (1) and (2), the second line is zero.

- 27,777

To find envelope by C-discriminant method, we eliminate $\lambda$ between

$$f(\lambda) \;=\; \lambda^2 P + \lambda Q + R =0, \; f^\prime(\lambda) \;=\; 2\lambda P + Q =0 \; $$

( the latter is the characteristic for the parameter $\lambda$ )

yielding:

$$ Q^2 = 4 P R $$

The method can be can be extended to 2,3 .. arbitrary number of parameters.

The method and result are same as that given by Blue.

- 42,260

This property can be considered as "natural" with the following archetypal case.

Consider the $(S,P)$ system of coordinates where

$$\begin{cases}S&=&x+y\\P&=&xy\end{cases} \ \ \text{for} \ \ (x,y) \in \mathbb{R^2}.$$

As $x,y$ are the (real !) roots of quadratic equation :

$$X^2-SX+P=0 \tag{1}$$

we must have : $$\underbrace{S^2-4P}_{\text{discriminant}} \ge 0.$$

Otherwise said,

$$P \le \tfrac14 S^2.$$

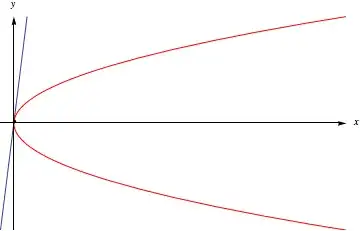

Therefore, the image in $\mathbb{R^2}$ of the mapping $(x,y) \mapsto (S,P)$ isn't the whole plane but the exterior of parabola ($\Pi$) with equation :

$$(\Pi): \ \ \ P=\tfrac14 S^2$$

Clearly :

the exterior of $(\Pi)$ for distinct real solutions.

$(\Pi)$ for the case of double roots ($x=y$).

the interior of $(\Pi)$ represents "points" $(S,P)$ yielding complex (conjugated) roots.

Now, re-interpreting (1) under the following form

$$(\Delta_{\lambda}) : \ \ \ \lambda^2-S\lambda+P=0 \tag{2}$$

defining a straight line $D_{\lambda}$, with a point of tangency when there is a double root to the quadratic (please note that (2) has the quadratic dependency described in the question).

A graphical representation :

Fig. 1.

The envelope of lines $(\Delta_{\lambda})$ is a conic curve, "border parabola" $(\Pi)$.

Remark 1 : The real signification of (2) is as follows : this line is the set of points $(S,P)$ having $X=\lambda$ as one of the roots of (1), the other one being retrieved for a given $S$ by $\mu=S-\lambda$.

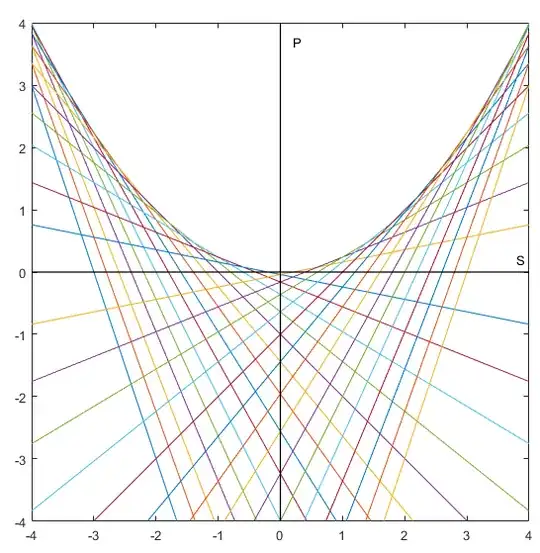

Remark 2 : Let us compare the previous situation with the case of the third degree equation reduced to its standard form :

$$x^3+px+q=0\tag{3}$$

with the equivalent set of lines with a third degree dependency on parameters :

$$(\Delta_{\lambda}) : \ \ \ \lambda^3+p\lambda +q=0$$

In this case (see Fig. 2), lines $(\Delta_{\lambda})$ envelope a curve which, instead of having implicit equation $S^2-4P=0$ has implicit equation :

$$4p^3+27q^2=0$$

which is the (reduced) discriminant of a third degree equation, itself with a third degree equation whose curve is called a semi-cubic parabola (which, despite its name, is no longer a conic curve).

Fig. 2.

MatLab program for fig. 2 :

clear all;close all;

set(gcf,'color','w')

f=@(x,y,L)(L.^3+x.*L+y);

for L=-3:0.1:3

g=@(x,y)f(x,y,L);

fimplicit(g,[-4,4],'Color','b');hold on;axis equal;

end;

plot([-4,4],[0,0],'k','LineWidth',1.5);hold on;

plot([0,0],[-4,4],,'k','LineWidth',1);hold on;

set(gca,'defaulttextfontsize',16)

text([3.6,0.2],[0.4,3.7],{'p','q'});hold on

fimplicit(@(x,y)(4*x.^3+27*y^2),[-4,4],'Color','k')

- 88,997