I just began reading Ordinary Differential Equations by Arnol'd, and in the first few paragraphs of the first chapter, Arnol'd says the following:

The theory of ordinary differential equations is one of the basic tools of mathematical science. This theory makes it possible to study all evolutionary processes that possess the properties of determinacy, finite-dimensionality, and differentiability.... A process is called deterministic if its entire future course and its entire past are uniquely determined by its state at the present time.... Thus, for example, classical mechanics considers the motion of systems whose future and past are uniquely determined by the initial positions and initial velocities of all points of the system.

I suspect that I'm misinterpreting this statement, because it seems entirely false to me that the past is uniquely determined by the present in classical mechanics. Are there not distinct states which evolve (under the laws of mechanics) into the same final state after some time?

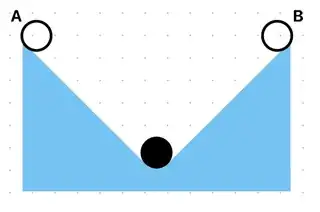

As a silly toy example, imagine that we record the state of a ball with four coordinates: its position in the 2D plane $(x,y)$, as well as its velocity vector $(\dot x,\dot y)$. Let's say the ball starts at the top of a ravine with no initial velocity (depicted below). Regardless of whether the ball starts in position A or position B at initial time $t_0$, we can model the evolution of the ball at all times $t\geq t_0$, allowing us to associate one state with every value of $t\in[t_0,\infty)$. That is, the future of the ball is uniquely determined by the present, as Arnol'd states. Crucially, however, the ball ends up in the same final state whether the initial state is in position A or position B. Hence, imagine that we first observe the ball at rest at the bottom of the ravine, so that time $t_0$ corresponds to the black ball in the picture below. There is no way to determine whether ball's past lies in state A or state B, so we cannot uniquely determine the ball's past based on its present state in this scenario.

This is just the first example that comes to mind, but surely there are endless other examples in classical mechanics where there are multiple distinct $t_{0}$ states that evolve into the same $t_{f}$ state, no? Wouldn't this mean that observing the $t_{f}$ state as the "present" moment prevents us from uniquely determining the state of the system at $t_0$? What am I misinterpreting about Arnol'd's statement?