Consider sticks of lengths $1^{1/k},\space 2^{1/k},\space 3^{1/k},\space\dots,\space n^{1/k}$ where $k,n\in\mathbb{Z^+}$.

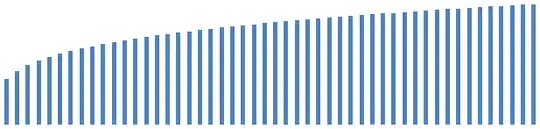

Here is an example with $k=4$ and $n=50$.

I have discovered that, as $n\to\infty$, the probability that three randomly chosen sticks can form a triangle approaches $1-\dfrac{1}{\binom{2k}{k}}$.

Is there a combinatorial proof for this fact?

Non-combinatorial proof

Suppose, for a given $n$, we have already chosen $a^{1/k}$ and $b^{1/k}$, and we are about to choose $c^{1/k}$.

If $a^{1/k},b^{1/k},c^{1/k}$ can be the side lengths of a triangle, then $\left|a^{1/k}-b^{1/k}\right|<c^{1/k}<a^{1/k}+b^{1/k}$, that is, $\left|a^{1/k}-b^{1/k}\right|^k<c<\left(a^{1/k}+b^{1/k}\right)^k$.

So the probability that $a^{1/k},b^{1/k},c^{1/k}$ can be the side lengths of a triangle is

$$\frac{\min\left(\left(a^{1/k}+b^{1/k}\right)^k,n\right)-\left|a^{1/k}-b^{1/k}\right|^k}{n}$$

(I'm ignoring the fact that the numerator should be an integer, and the fact that we cannot choose the same stick twice; these facts will be irrelevant when we take the limit as $n\to\infty$.)

Then we take the average as $a$ and $b$ run from $1$ to $n$.

$$\frac{1}{n^2}\sum_{a=1}^n\sum_{b=1}^n\frac{\min\left(\left(a^{1/k}+b^{1/k}\right)^k,n\right)-\left|a^{1/k}-b^{1/k}\right|^k}{n}$$

As $n\to\infty$, the limiting probability is the integral

$$\int_0^1\int_0^1\left(\min\left(\left(x^{1/k}+y^{1/k}\right)^k,1\right)-\left|x^{1/k}-y^{1/k}\right|^k\right)\mathrm dx\mathrm dy$$

$$=\int_0^1\left(\int_0^{(1-y^{1/k})^k}\left(x^{1/k}+y^{1/k}\right)^k\mathrm dx+\int_{(1-y^{1/k})^k}^1 1\mathrm dx-\int_0^y\left(y^{1/k}-x^{1/k}\right)^k\mathrm dx-\int_y^1\left(x^{1/k}-y^{1/k}\right)^k\mathrm dx\right)\mathrm dy$$

which can be evaluated using hypergeometric functions, and simplifies to

$$1-\frac{1}{\binom{2k}{k}}$$

Desmos agrees.

In fact, $k$ does not have to be a positive integer; it can be any positive real number. (Fun fact: As $k\to 0$, the probability that the three sticks can form a triangle approaches $\dfrac{\pi^2}{6}k^2$.) But since I am looking for a combinatorial proof, I am restricting $k$ to positive integers.

Generalization

Numerical investigation suggests the following generalization (which I am not asking to prove):

As $n\to\infty$, the probability that $m$ randomly chosen sticks can form an $m$-gon approaches $1-\dfrac{k!^{m-1}}{((m-1)k)!}$.

Context

This is another question of mine about the probability that three sticks can form a triangle. My previous question was here.