We have the following integral to solve $$ I = \int_0^{\infty} \frac{x^{\frac{1}{3}}}{1 + x^2} dx $$ I've managed to solve this integral. Using the substitution $u = x^2$ we can show that $I = \frac{1}{2}B(\frac{2}{3}, \frac{1}{3})$, where $B$ is the Beta-function. We use the Gamma representation of the Beta-function, and, finally, Euler's reflection formula to show that $I = \frac{\pi}{\sqrt{3}}$.

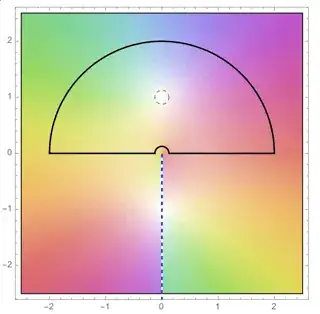

Now I want to try to solve the same integral using contour integration. As contour we take the upper half circle $\Gamma_R$ with radius $R > 1$. We have one pole at $i$ within the upper half circle $\Gamma_R$. Using the residue theorem we find on the one hand (we write $z$ instead of $x$, as the problem becomes complex) $$ \oint_{\Gamma_R} \frac{z^{\frac{1}{3}}}{1 + z^2} dz = \oint_{\Gamma_R} \frac{z^{\frac{1}{3}}}{(z - i)(z + i)} dz = i 2 \pi \frac{i^{\frac{1}{3}}}{i2} = \pi i^{\frac{1}{3}}. $$ On the other hand $$ \oint_{\Gamma_R} \frac{z^{\frac{1}{3}}}{1 + z^2} dz = \int_{-R}^{R} \frac{z^{\frac{1}{3}}}{1 + z^2} dz + \int_{0}^{\pi} \frac{R^{\frac{1}{3}} e^{i \frac{\theta}{3}}}{1 + R^2 e^{i2\theta}} iRe^{i\theta} d\theta. $$ Letting $R \to \infty$, the second integral goes to zero because the denominator dominates the nominator. We have $$ \pi i^{\frac{1}{3}} = \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \frac{z^{\frac{1}{3}}}{1 + z^2} dz = \int_{-\infty}^{0} \frac{z^{\frac{1}{3}}}{1 + z^2} dz + \int_0^{\infty} \frac{z^{\frac{1}{3}}}{1 + z^2} dz = \int_{0}^{\infty} \frac{(-u)^{\frac{1}{3}}}{1 + u^2} du + I, $$ where we used the substitution $u = -z$ in the first integral, and observed that the second integral is our target integral $I$. We can write $i = e^{i\frac{\pi}{2}}$ so that $i^{\frac{1}{3}} = e^{i\frac{\pi}{6}} = \frac{\sqrt{3}}{2} + i \frac{1}{2}$. As $u$ is non-negative, we can write $(-u)^{\frac{1}{3}} = (e^{i\pi} u)^{\frac{1}{3}} = e^{i\frac{\pi}{3}} u^{\frac{1}{3}} = (\frac{1}{2} + i\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}) u^{\frac{1}{3}}$. Plugging in these equalities in the equation above gives $$ \pi \frac{\sqrt{3}}{2} + i \frac{\pi}{2} = \int_0^{\infty} \frac{(\frac{1}{2} + i\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}) u^{\frac{1}{3}}}{1 + u^2}du + I = \frac{3}{2} I + i \frac{\sqrt{3}}{2} I. $$ Taking either the real or imaginary part of this equation gives the target integral $I = \frac{\pi}{\sqrt{3}}$.

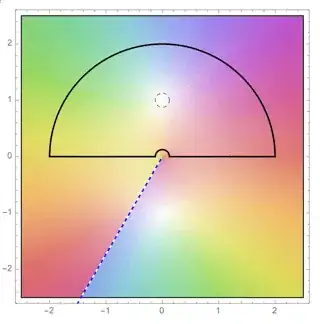

So far, so good. But here is my question. There are multiple cube roots possible. Two other solutions for $i^{\frac{1}{3}}$ are $-i$ and $-\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2} + i \frac{1}{2}$, two other solutions for $(-1)^{\frac{1}{3}}$ are $-1$ and $\frac{1}{2} - i \frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}$. If I use any of the other cube roots in the method above, I won't get the solution $I = \frac{\pi}{\sqrt{3}}$. For one of them I even get that something non-zero is equal to zero.

- Why do the other cube roots not work for this method?

- How do I know, beforehand, which cube root to take? How does this work in general for any $z^{\frac{1}{n}}$, where $n > 2$?

Thank you in advance!