You have three definitions of differentiability:

For functions $f : U \to \mathbb R$ with an open $U$ and $a \in U$.

For functions $f : D \to \mathbb R$ with an arbitrary $D$ and an interior point $a$ of $D$.

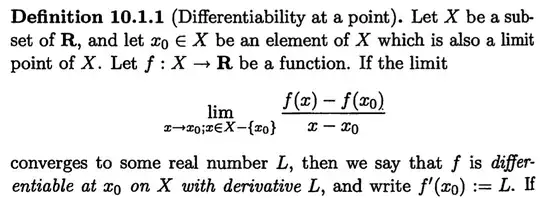

For functions $f : X \to \mathbb R$ with an arbitrary $X$ and a limit pont $a \in X$ (Tao).

Clearly 3. is the most general definition which covers 2. (since each interior point of $D$ is a limit point of $D$), and 2. covers 1. because each point of an open $U$ is an interior point of $U$.

In contrast to 1. and 2. Tao's definition covers the differentiability of function $f : [a,b] \to \mathbb R$ at the boundary points $a, b$ of closed intervals. This is certainly useful. In many books boundary points are treated as separate cases by introducing the concepts of left hand and right hand derivatives.

However, Tao's definition also covers more exotic cases like functions $f : \mathbb Q \to \mathbb R$ (note that each rational number is a limit point of $\mathbb Q$). Whether one considers this to be useful is everybody's personal opinion.

Note that Tao's definition does not cover isolated points of $X$. For such points there does not exist limit $\lim_{x \to a, x \in X \setminus \{a\}}\frac{f(x)- f(a)}{x-a}$.

Sometimes one can also find the following definition based on 1. :

$f : X \to \mathbb R$ is differentiable in $a \in X$ if there exists an open neighborhood $U$ of $a$ in $\mathbb R$ and function $\phi : U \to \mathbb R$ such that $\phi \mid_{U \cap X} = f \mid_{U \cap X}$ and $\phi$ is differentiable at $a$.

It seems obvious to define $f'(a) = \phi'(a)$, but for an isolated point $a$ this does not make sense because any function $\phi$ defined on a sufficiently small open neighborhood $U$ can be used.

However, for a limit point $a$ of $X$ we obviously get

$$\lim_{x \to a, x \in X \setminus \{a\}}\frac{f(x)- f(a)}{x-a} = \phi'(a) .$$

This shows that differentiability (in a limit point) in the above sense implies differentiability in Tao's sense.

Also the converse is true for a limit point $a$. In fact, let $f : X \to \mathbb R$ be differentiable at $a$ in Tao's sense. Define

$$\phi: \mathbb R \to \mathbb R, \phi(x) = \begin{cases} f(x) & x \in X \\ f(a) + f'(a)(x-a) & x \notin X\end{cases}$$

You can easily check that $\phi$ is differentiable at $a$ and $\phi \mid_X = f$. Moreover, $\phi'(a) = f'(a)$.

If you want, have a look at Quotient Rule: Why does Tao assume $g$ is non-zero on $X$? You will see that Tao's definition sometimes implicitly occurs when one considers the quotient rule.

Can someone help me understand whether openness and interiority are necessary in order to define differentiability?

It is not necessary for functions defined on some $X \subset \mathbb R$. Tao's definition has benefits as explained above.

However, when we deal with multivariable functions $f: X \to \mathbb R$ defined on some $X \subset \mathbb R^n$, we are well advised to consider only interior points of $X$ as done in the paper linked in your question. We could define differentiability in limit points, but the problem is that in general we do not get a well-defined derivative $f'(a)$. Such a derivative is a linear map which allows to approximate $f$, but is is not representable as a limit as in the case $n = 1$. For interior points it is easy to see that we get a well-defined $f'(a)$. One could also consider points which are no interior points of $X$ at the price of rather technical assumptions on $a$ and $X$, and that is why it is usually not done in textbooks on multivariable calculus.