OBSERVATION :

Every Author & every Book will use some convenient ways to Define the real numbers , then Define limits , Continuity , Derivatives , Etc.

Axioms involved might vary a little here & there.

Such ways are "Essentially Equivalent" , with at most minor variations.

Here , "Tao" uses one way while "Bartle & Sherbert" use some other way , which are "Essentially Equivalent" when we think about it.

DISCUSSION :

Consider that Tao uses the more general "Sub-Sets" of $R$ & "limit Points" , when talking about Continuity & Derivatives & Etc.

Compare that with Bartle & Sherbert , who use the less general "Intervals" & "limits" , when talking about Continuity & Derivatives & Etc.

Even earlier in the theory , Tao uses "Cauchy sequence" to introduce real numbers.

Compare that with Bartle & Sherbert , who use "Completeness Property" to introduce real numbers earlier in the theory.

Naturally , the variations will later dictate how the theorems are stated & proved.

Specifically going to the OP Question here :

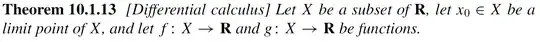

We can see that Tao uses limit Point & Non-Zero $g$ in the Sub-Set , when stating the Quotient rule. The Proof is hinted at in the Exercise 10.1.4 (2016 Edition) where it says "use the limit laws in Proposition 9.3.14"

Page 223 (2016 Edition) :

"Proposition 9.3.14 (Limit laws for functions). Let $X$ be a subset of

$R$, let $E$ be a subset of $X$, [....] If $c$ is a real number, then $cf$ has a limit $cL$ at $x_0$ in $E$. Finally, if $g$ is non-zero on $E$ (i.e., $g(x) \ne 0$ for all $x ∈ E$) and $M$ is non-zero , then $f/g$ has a limit $L/M$ at $x_0$ in $E$."

So here too , we have Non-Zero $g$ in the Sub-Set , not just at a Point.

Proof of that Proposition refers to Theorem 6.1.19 (Limit Laws) in Page 132 (2016 Edition) :

Here too the Condition for $a_n/b_n$ is that $b_n \ne 0$ for all $n$.

In short , the earlier theorems (which Tao wants to use to State & Prove the quotient rule) already use Non-Zero $g$ at all Points in the Sub-Set , which carries over to the later theorems , including the quotient rule.

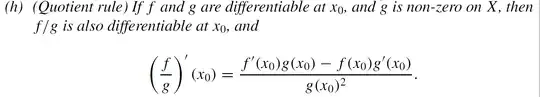

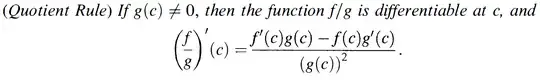

Compare with Bartle & Sherbert , who state the quotient rule with Interval $I$ & Non-Zero $g(c)$ at Single Point.

The Proof given (Page 164) then uses the new Interval $J$ where $g$ is always Non-Zero , not just at a Single Point.

This $J$ uses theorem 4.2.9 to claim Non-Zero $g$ at all Points.

That theorem (Page 115) says that (A) at a Point $x=c$ , when limit $lim (f) < 0$ , then there is a neighborhood where $f < 0$ always (B) at a Point $x=c$ , when limit $lim (f) > 0$ , then there is a neighborhood where $f > 0$ always

In short , Bartle & Sherbert take Non-Zero $g$ at a Point & then show that we must have Non-Zero $g$ in some Interval (not just at that Point) for quotient rule.

SUMMARY :

We can then see that Both ways are Equivalent : One way apriori takes Non-Zero $g$ at all Points , the other way takes Non-Zero at a Point & then shows that we must have Non-Zero $g$ at all Points.

Why Tao wants Non-Zero in Sub-Set ? To use the Previous theorems which require it. Tao has no easy theorem to convert "Non-Zero at Point" to "Non-Zero in Sub-Set" , which is required for quotient rule.

Why Bartle & Sherbert uses Non-Zero at Point ? There are Previous theorems which easily convert "Non-Zero at Point" to "Non-Zero in Interval". That Criteria is required for quotient rule.