I am trying to plot the standard bounds of simple Brownian motion (implemented as a Wiener process), but I have found some difficulties when drawing the typical equations:

- When trying to plot the bound given by the Law of the iterated logarithm: $ f_1(t) = \sqrt{2t\log(\log(t))}$, it fails to work at $t = [0 ; 1]$, because $\log(t) < 0$ so $\log(\log(t))$ is undefined.

- Then, I tried to fix it leting $ f_2(t) = \sqrt{2t\log(\log(t+1))}$, but again gives problems because it becomes "imaginary" due the square root of $\log(\log(t+1))<0$ on $t = [0 ; 1]$.

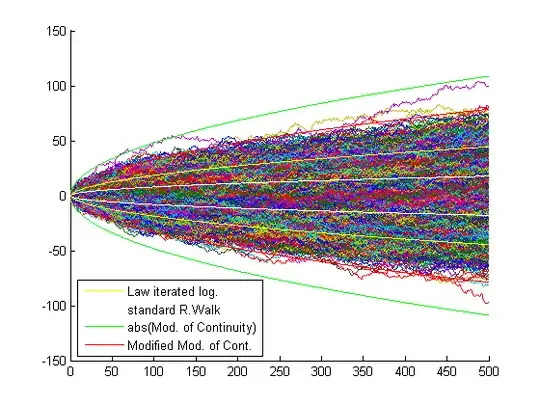

- So I tried again using $ f_3(t) = \sqrt{2t\log(\log(t+1)+1)}$ as the bound defined by the Law of the iterated logarithm, and it works (is well defined, and when $t \rightarrow \infty $ should reach a "similar" limit than the first attempts). Unfortunately, when plotted against many realizations of the Brownian paths, the bound is overpassed too many times at the start to be a good "tight" bound (it's "too tight").

- So, I tried another bound shown in the Wiener processes' Wikipedia named as "Modulus of Continuity", $f_4(t)=\sqrt{2t\log(\log(1/t))}$, which also have the "logarithm" problems as previous attempts for $t = [0 ; 1]$ (fixables), but it shows to be imaginary for almost all the domain $t > 0$. Not too promising (even when works good for valued near zero), but since it is also proportional to the first attempts (because $\log(1/t) = - \log(t)$), I tried using the absolute value of the adapted function for the "Modulus of Continuity" as the envelope-bound: $$f(t)_\pm=\pm\sqrt{2t\sqrt{\pi^2+{\log(1+\log(1+t))}^2}}$$ Which works really good as a tight bound for the Brownian realizations. Also at the beginning their behavior $\propto \sqrt{2t\pi}$ remembers me the bounds for standard 1D random walk which is $\sqrt{2t/\pi}$.

Example of tested bounds and Brownian realizations: https://i.sstatic.net/c6GQl.png

The proposed bounds $f(t)_\pm$ are in green.

The red one is just a modification of the green one: $g(t)_\pm=\pm\sqrt{t\sqrt{\pi^2+{\log(1+\log(1+t))}^2}}$ which fits tight as an envelope of the shaded area. Both quite wider than the clasic one sigma deviation of a nornalized Brownian path ($\sigma=1$) which should be proportional to $\sqrt{t}$.

Actually it works so good, that I don't know if it is just a coincidence (maybe I made a mistake when defining the Brownian paths), but I don't found this bound in any website, so if right, it could be useful for everybody so I left it here, but certainly, I don't have the ability to probe anything related to it:

- If it is "mathematically" right? (such as the "real" form of the law of the iterated logarithm).

- If it is "tight" as an "almost-sure" true limit? (such something outside by a value $\epsilon \to 0$ don't going to be surpassed almost surely infinitely many times, but something inside will do).

- If it is going to be surpassed infinitely many times or not? (i It is really a frontier or not?)

- It is a "better" metric for/than the Law of the Iterated Logarithm?

- It is a "better" metric for/than the Modulus of Continuity?

- To which percentile these bounds are corresponding?, etc... (I tried to fit it in a gaussian distribution but it don't fit a constant-term deviation).

I hope you can help to tell me if is "mathematically" the "right envelope function, or just a mistake that has a beauty plot.

I left the code so you can play with it, is specially better at the first values (as it was mentioned, standard metrics fails here near zero).

Beforehand, thanks you very much.

The Matlab code I use:

length = 500;

N = 10000;

white_noise = wgn(length-1,N,0);

simple_brownian = zeros(length,N);

t = 0:1:(length-1);

%Wiener brownian vectors starting at zero

for m = 1:1:N

simple_brownian(2:1:length,m) = cumsum(white_noise(:,m));

end

% Law of iterated logarithm (modif)

envp = sqrt(2.t.(log(1+log(1+t))));

envm = -envp;

% Proposed bounds

envp2 = sqrt(2.t.sqrt(pi^2+log(log(t+1)+1)).^2);

envm2 = -sqrt(2.t.sqrt(pi^2+log(log(t+1)+1)).^2);

figure(1), hold on,

plot(t,envp,'y',t,envm2,'g',t,envp2,'g',t,envm,'y'),

legend('Law iterated log.','Proposed bounds'),

plot(t,simple_brownian),

plot(t,envp,'y',t,envm2,'g',t,envp2,'g',t,envm,'y'),

hold off;

Added later

About point (5), commenting something mentioned in the comments: as $t\to \infty$ the Law of the Iterated Logarithm such as $f_{\pm}(t)$ will behave similar in the sense their fraction $\lim_{t\to \infty} \frac{f_\pm(t)}{\text{LIL}(t)}\to 1$ as can be seen in Wolfram-Alpha.

I think since the Modulus of continuity kind of show how much could change at max some function (as a kind-of-derivative when differentiation is undefined), it should fit the envelope I am looking for.

After some trials I think the found bound $f_{\pm}(t)$ could be improved just adjusting by just one displacement the mentioned Modulus of continuity of the Wiener process as: $$h(t)_\pm=\left|\sqrt{2t\log\left(\log\left(\frac{1}{t\color{red}{+1}}\right)\right)}\right|=\pm\sqrt{2t\sqrt{\pi^2+{\log(\log(1+t))}^2}}$$

But also, the classic LIL could be improved as:

$$k(t)_\pm = \pm\sqrt{2t\log(\log(t\color{red}{+e}))}$$

So for me is not clear at all which one is fulfilling being the "real envelope" of a wiener process and behaving as a LIL should do: as example $k_\pm(t)$ behaves more similar to $g_\pm(t)$ than it do to $h_\pm(t)$ (this is why, based on the plots, I think is $h_\pm(t)$ the better one).

Also, since at the beginning $h_\pm(t)$ behaves similar to $h_\pm(t) \sim \sqrt{2\pi t}$, neither is clear for me that if the standard deviation of a Brownian motion is $\sigma = \sqrt{t}$, then how should be interpreted this envelope corresponding to a standard deviation of $\sqrt{2\pi}\sigma$.