There is actually nothing wrong with choosing an arbitrary fixed point on the circle as your "origin" and giving each point a coordinate equal to the distance from the origin to that point counterclockwise along the circle.

In this coordinate system, three points $A,B,C$, each placed randomly on the circle with a uniform probability distribution on the circumference, each probability independent of the other two points, will be placed at three coordinates on the circle.

If we also call those coordinates $A,B,C$ respectively,

then the coordinates $A,B,C$ are real-valued random variables that are i.i.d.

and uniformly distributed on $[0,1).$

Where you run into trouble is when you try to say $A < B < C$ or $C < B < A.$

It is certainly true that the three points will (with probability $1$)

be placed in one of two ways: either $(1)$ a counterclockwise arc starting at $A$ will reach $B$ first and $C$ second, or $(2)$ a counterclockwise arc starting at $A$ will reach $C$ first and $B$ second.

It is also true that in the case $(2)$ just described, you can equally well say that a counterclockwise arc starting at $C$ will reach $B$ first and $A$ second;

provided all three points are distinct, the two descriptions of this case are equivalent.

But none of this implies that $A < B$ or $B < C$ in case $(1),$ because you have forgotten that all three numbers $A,B,C$ are distances from a previously chosen fixed point we called the "origin."

The statement $A<B<C$ is a statement about the relative placement of four points (the origin, $A$, $B$, and $C$): namely that by starting at the origin and going counterclockwise, you will encounter $A$ first, $B$ second, and $C$ last. And while it is true that there are really only two ways to sequence three points around a circle, there are much more than two ways to sequence four points around a circle.

I suggested here that if you really want to only deal with cases $A<B<C$ and $C<B<A$ you would have to give up the i.i.d. assumption. But I think a better approach is to keep the i.i.d. assumption and give up the idea of restricting your possible arrangements to only the cases

$A<B<C$ and $C<B<A$.

I have spent an awful lot of text discussing the chains of inequalities $A<B<C$ and $C<B<A$ and the two cases $(1)$ and $(2)$, but only reason I have done this is to show why these ideas are wrong ways to think about this problem.

I'm going to draw a line now (literally) under this paragraph and once we cross that line we will never see those inequalities or cases again.

To recapitulate, we have three random points on a circle, and the locations of those three points (measured counterclockwise from some fixed point) are the three i.i.d. real random variables $A,B,C$ each uniformly distributed on $[0,1).$

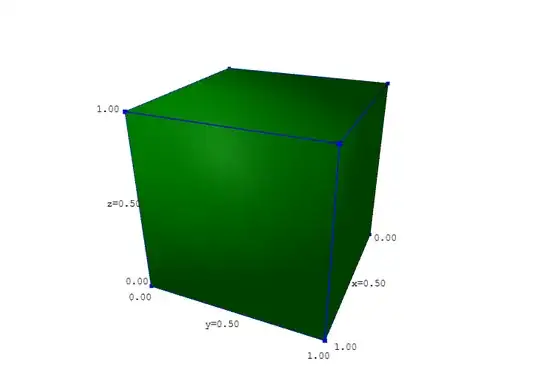

The joint distribution of these three variables is a uniform distribution on the cube $[0,1) \times [0,1) \times [0,1),$ represented by the figure below:

Let $B$ be the coordinate along the vertical axis in this figure, and let $A$ and $C$ be the other two coordinates.

Now let's define $X$ as the length of the shortest counterclockwise arc starting at $B$ and ending at $A$.

That's the definition of $X$; we'll work out the formulas as needed to satisfy that definition.

Consider the example where $A$ is $90$ degrees counterclockwise from $B$, that is, the counterclockwise distance from $B$ to $A$ is $0.25.$

If the coordinate of $B$ is $B = 0.3,$ the coordinate of $A$ is easily found:

$A = 0.3 + 0.25 = 0.55.$

But if $B = 0.9,$ things work a little differently. The first $0.1$ unit of length in the counterclockwise direction gets us from $B$ to the origin; we still have to go another $0.15$ units of length from the origin in order to finish the arc from $B$ to $A$, and therefore the coordinate of $A$ is $A = 0.15.$

That is, simple addition would have given $0.9 + 0.25 = 1.15$, but when we passed the origin we instantly subtracted $1$ from the coordinate (because we start counting distance from the last time we crossed the origin), and therefore the result is

$A = 0.9 + 0.25 - 1 = 0.15.$

The rule therefore is: if the arc from $B$ to $A$ goes past the origin, that is,

if $A < B,$ then $A = B + X - 1$ and therefore $X = A - B + 1$;

but if the arc does not go past the origin, that is, if $B < A,$

then $A = B + X$ and $X = A - B.$

Note that the inequality $B < A$ doesn't say anything about the positions of $A$ and $B$ relative to each other; it just says that we can get from $B$ to $A$ in a counterclockwise direction without passing through the arbitrary point we chose as the origin of coordinates.

Next, let's define $Y$ as the length of the shortest counterclockwise arc starting at $B$ and ending at $C$. Using the same reasoning we used for $X$, we can show that this definition implies that

$Y = C - B + 1$ if $C < B$ and $Y = C - B$ if $B < C.$

By definition, since $X$ is the shortest counterclockwise arc from $B$ to $A$, $X$ cannot be less than $0$ (you have to go counterclockwise, not clockwise!) and $X$ cannot be greater than $1$ (because you will certainly reach $A$ before you circle all the way around to $B$ again).

It should be clear that in fact the possible values of $X$ are exactly $[0,1),$

and likewise with $Y$.

There are at least two ways to prove that $X$ and $Y$ are i.i.d. and uniformly distributed on $[0,1).$

In my opinion, the easiest and most intuitive proof is that if the distribution of $X$ was not uniform, then if you found out the location of $B$ you would know that $A$ was more likely to occur in some arc of the circle than in in some other equal-sized arc. That is, the probability distribution of $A$ conditioned on a value of $B$ would be different from the unconditional distribution of $A.$

Therefore $B$ and $A$ would not be independent.

But since $B$ and $A$ are independent, $X$ must be uniformly distributed on $[0,1).$ Likewise for $Y$.

The second part of the proof is that if $X$ and $Y$ were not independent, then if you knew the locations of $A$ and $B$ you would know $X$; the distribution of $Y$ conditioned on $X$ might not be the same as the unconditioned distribution, that is, it might not be uniform; and therefore you would be able to say (based on the knowledge of $A$ and $B$) that $C$ is more likely to occur in one arc of the circle than in some other arc of equal length. But that would mean $C$ would not be independent of $A$ and $B$. Since we know that $C$ is independent of $A$ and $B$, $Y$ must be independent of $X$.

Another, much longer proof can be done by constructing the joint distribution of $B,$ $X,$ and $Y.$

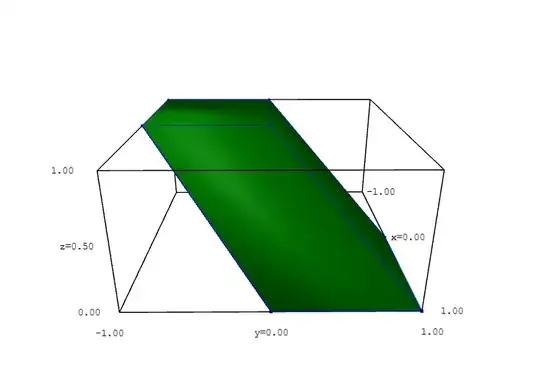

We start by considering a different joint distribution: the joint distribution of $B,$ $x = A - B,$ and $y = C - B.$

(Lower-case $x$ and $y$ for simple difference of coordinates rather than the length of a counterclockwise arc.)

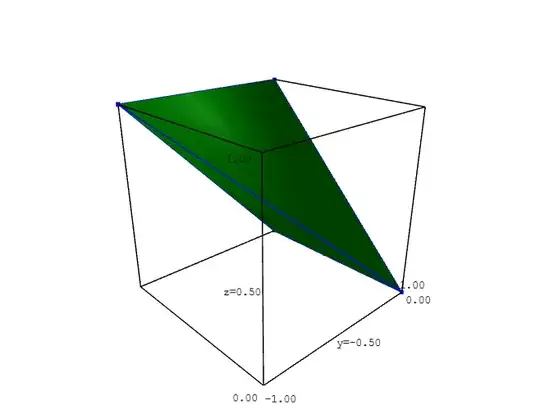

This distribution looks something like the graph below,

where the vertex in the lower right of the figure represents the outcome

$x = A-B=1-\epsilon,$ $y = C-B=1-\epsilon,$ $B=0$

and the vertex in the upper left represents the outcome

$x=A-B=-1,$ $y=C-B=-1,$ $B=1-\epsilon.$

(I write $1-\epsilon$ instead of $1$ because technically it is not possible for any of these quantities to be exactly equal to $1$.)

If we take a horizontal slice of this distribution at any particular value of $B,$

the distribution in that slice will be uniform over the square

$[-B,1-B) \times [-B,1-B)$,

that is, the square such that $-B \leq x = A - B < 1 - B$

and $-B \leq y = C - B < 1 - B$.

And since $B$ is uniformly distributed, any equally-very-thin horizontal slice is equally likely, so the distribution over the entire volume is uniform;

the density is $1$ throughout.

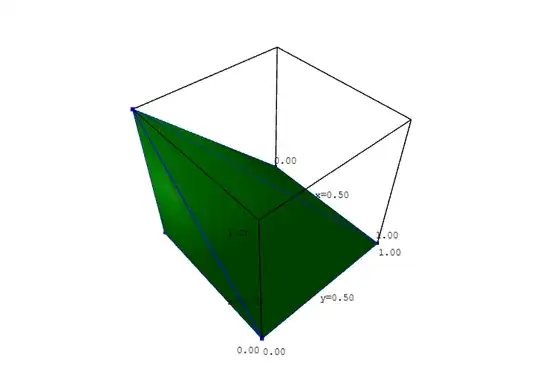

But the only part of this distribution that directly represents part of the distribution of $X$ and $Y$ is the part where $A > B$ and $C > B,$ that is, the

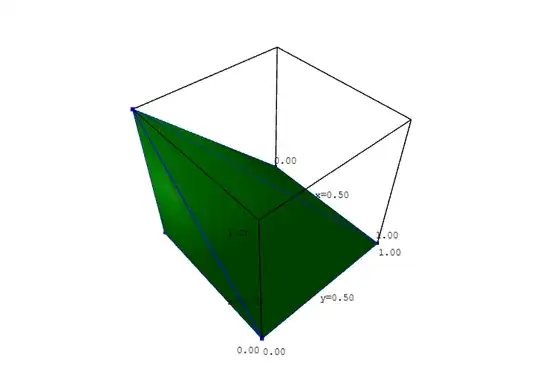

square-based pyramid below:

Within this pyramid, whatever $A - B$ and $C - B$ came out to be, $X$ and $Y$ come out to those values, respectively.

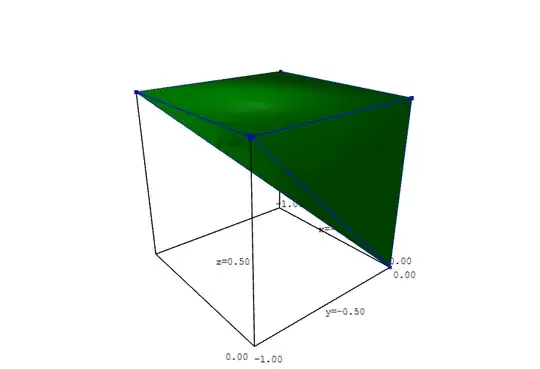

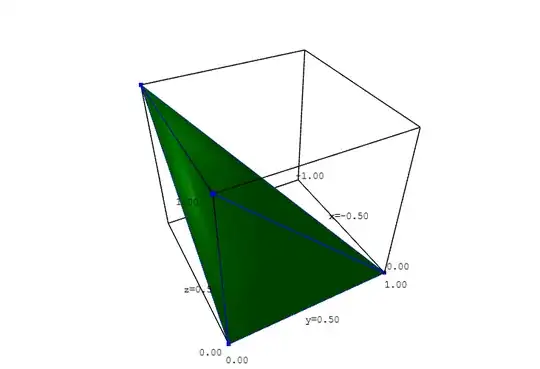

The case where $C > B$ but $A < B$ is represented by the following tetrahedron bounded by the equations $x = A - B \leq 0,$ $x + B = A \geq 0,$

$y = C - B \geq 0,$ $y + B = C \leq 1.$

But since $X = A - B + 1 = x + 1$ in this case, this part of the joint distribution of $X,$ $Y,$ and $B$ is translated $1$ unit in the $x$ direction so that it falls inside the cube $[0,1) \times [0,1) \times [0,1).$

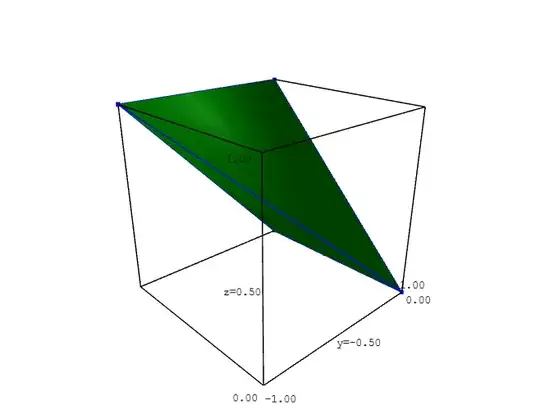

The case where $A > B$ but $C < B$ is represented by the following tetrahedron bounded by the equations $x = A - B \geq 0,$ $x + B = A \leq 1,$

$y = C - B \leq 0,$ $y + B = C \geq 0.$

But since $Y = C - B + 1 = y + 1$ in this case, this part of the joint distribution of $X,$ $Y,$ and $B$ is translated $1$ unit in the $y$ direction so that it falls inside the cube $[0,1) \times [0,1) \times [0,1).$

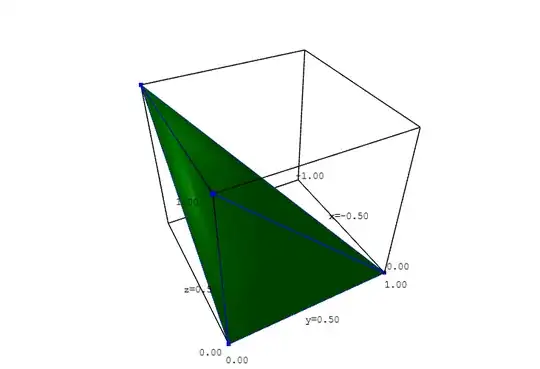

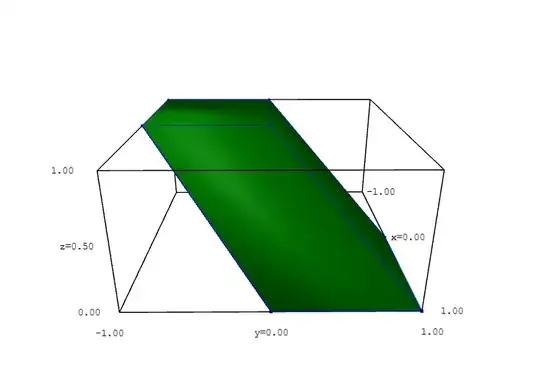

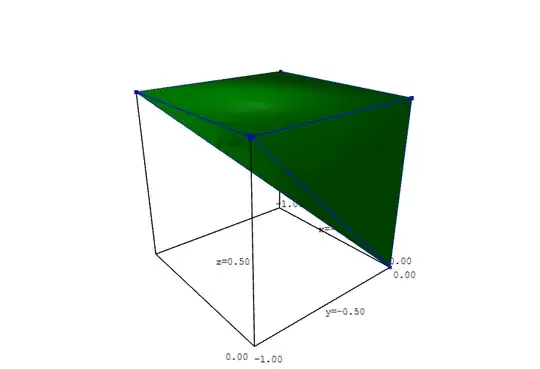

The final case, where $A < B$ and $C < B$, is represented by the inverted square-based pyramid in the figure below,

bounded by the equations $x = A - B \leq 0,$ $x + B = A \geq 0,$

$y = C - B \leq 0,$ $y + B = C \geq 0,$ $B < 1$:

In this case $X = x + 1$ and $Y = y + 1,$ that is, this pyramid is translated by $1$ unit in both the $x$ and $y$ directions in order to become the part of the joint distribution of $X,$ $Y,$ and $B$ for this case.

Again this places the pyramid inside the cube $[0,1) \times [0,1) \times [0,1).$

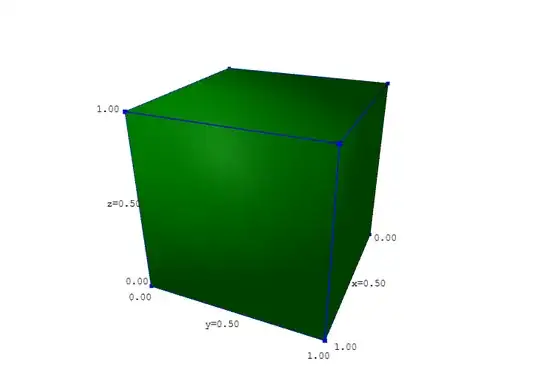

When the four parts of the distribution of $X$ and $Y$ are assembled inside the cube

$[0,1) \times [0,1) \times [0,1)$ in this way, they exactly fill the cube without overlapping. Moreover, since the distribution of $A-B,$ $C- B,$ and $B$ from which these pieces were taken has uniform density $1,$ so does the distribution of

$X,$ $Y,$ and $B$ within the cube $[0,1) \times [0,1) \times [0,1).$

Therefore the variables $X,$ $Y,$ and $B$ are i.i.d. uniformly distributed over

$[0,1).$ It follows a fortiori that the variables

$X$ and $Y$ are i.i.d. uniformly distributed over $[0,1).$

Personally I like the first proof much better. The second proof takes a lot more work for the construction and requires careful checking to make sure that the four pieces of the distribution really fill the cube without overlapping.