I think Pi (the relation between the circumference of a circle and it's diameter) has different values in non-Euclidean geometries. I am interested in what is invariant across all geometries. I wonder if the golden ratio may be invariant across spherical and/or hyperbolic geometries.

-

2The ratio of the circumference to the radius in, say, hyperbolic geometry is not a constant. see, e.g., this As to the golden ratio, well...how are you defining it? – lulu Dec 10 '20 at 23:24

-

1Pi and the golden ratio both have many (equivalent) mathematical definitions, and not just the simple geometric one(s). The ratio of a circle's cirumference to its radius may vary, but $\pi$ does not. When you ask whether 'the golden ratio' is invariant you have to be very specific about what quantity you're asking about. – Steven Stadnicki Dec 10 '20 at 23:26

-

I am thinking of the geometric "picture" of phi. Divide a line segment at a point on the segment such that the ratio of the smaller sub-segment to the larger sub-segment is equal to the ratio of the larger sub-segment to the original line segment. This seems simpler than a circle, which needs parameters (center and radius) so there are at least two parameters necessary to make a circle; but I think there are no parameters necessary for the golden ration other than the line segment (i.e. any line segment.) – Joe Cash Dec 10 '20 at 23:30

-

@Steven Stadnicki: I think Pi does vary. It is different in spherical geometries, and is not even invariant within a fixed (or given) spherical geometry (I think.) The fact that the definitions are equivalent suggest there is some kind of objective "thing" underlying all the concepts. That's not to say the "thing" is material or physical; but its' defining properties are invariant. I wrote another comment above where I discuss what I mean by the golden ratio. – Joe Cash Dec 10 '20 at 23:36

-

https://www.maa.org/external_archive/devlin/devlin_05_07.html – Will Jagy Dec 11 '20 at 00:03

-

Actually, in the limit as radius goes to zero, the value $\pi$ is achieved. On a sphere, the expressions involve trig functions, in thehyperbolic plane $\cosh$ and $\sinh$ http://zakuski.utsa.edu/~jagy/papers/Intelligencer_1995.pdf – Will Jagy Dec 11 '20 at 00:05

-

@JoeCash The 'circle ratio' varies in non-euclidean geometries — but when it varies it is no longer $\pi$. Otherwise we could not say that $\pi$ is half the period of the sin function, or that it is $\sqrt{6\cdot\sum_n \frac1{n^2}}$, or any of the other multitude of ways of specifying it. – Steven Stadnicki Dec 11 '20 at 00:35

-

The Wikipedia article Golden Ratio states "the division of a line into "extreme and mean ratio" (the golden section)" which implies that it was defined as a ratio of line segments. This is still the same in NonEuclidean geometries. – Somos Dec 11 '20 at 01:50

-

@Steven Stadnicki: I am calling it Pi because it is the ratio of the diameter of a circle to the circumference of the circle. What are the properties of a "circle" in an elliptical geometry? How about the sin function in an elliptical or maybe a hyperbolic geometry? – Joe Cash Dec 12 '20 at 06:51

-

I'm looking for what is invariant across all (or many) geometries. I think invariants are interesting to orient on. The speed light is an invariant in physics, for example. There are probably better examples. – Joe Cash Dec 12 '20 at 06:54

-

This may clarify what I mean by the golden ratio: Given line segment AB, place a point C on AB such that the lengths of AB, AC and BC conform to the following proportion: AB:AC::AC:CB – Joe Cash Dec 12 '20 at 06:54

-

@Somos: That's what I suspect might be true; but I'm not certain. The fact that Pi is not invariant surprised me. Maybe I'll be surprised by the golden ratio. – Joe Cash Dec 12 '20 at 07:01

-

I think it may be that, in a non-Euclidean geometry (like a hyperbolic geometry) the length of a line segment may vary depending on where in the space the endpoints are placed. I'm only basing this on Escher's drawings of what look like bats tiling a hyperbolic sphere. The bats on the periphery of the sphere are much smaller than the bats at the center of the hyper-sphere. In Euclidean 3-Space you can place four points so they are all equidistant. In some non-Euclidean spaces you can place 5 points equidistant from each other. Try that in Euclidean 3-space. – Joe Cash Dec 12 '20 at 07:12

-

@JoeCash: "I think it may be that, in a non-Euclidean geometry (like a hyperbolic geometry) the length of a line segment may vary depending on where in the space the endpoints are placed." This is not the case. Escher drawings mimic the Poincare Disk Model of the hyperbolic plane. In the model —that is, to our eyes — things appear smaller near the bounding circle; however, in the geometry, measurements are completely uniform. Check the link for formulas explaining how distances are supposed to be interpreted. – Blue Dec 12 '20 at 10:09

2 Answers

Insofar as the Golden Ratio $\phi$ is defined as a number satisfying $\phi^2=\phi+1$ (this is equivalent to the extreme/mean ratio division description), the ratio belongs to any geometry where (loosely speaking) lines are effectively rulers with continuous and uniform real-number labels for points. The existence of $\phi$ in this sense is no more or less remarkable than the existence of $\frac12$. Even $\pi$ as a number exists in such contexts: it lives just past $3$ on the ruler. In a "uniform" geometry (such as the Euclidean, Spherical, and Hyperbolic planes), the rulers don't change from here to there, so the "invariance" of $\phi$ and $\frac12$ and $\pi$ as numbers is baked-in: every segment has a point dividing it in the ratio $1:x$ for any number $x$. As a matter of numerics, there's really nothing to discuss.

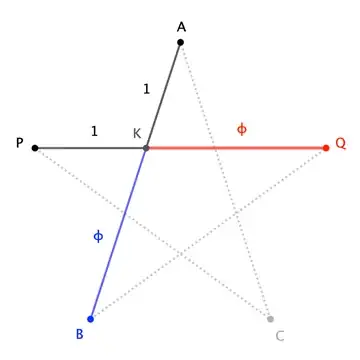

Where things get interesting is investigating whether a value like $\phi$ "arises" from the geometry. For instance, one way $\phi$ arises in Euclidean geometry is via the regular pentagram:

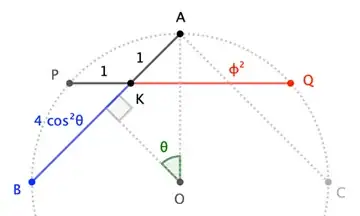

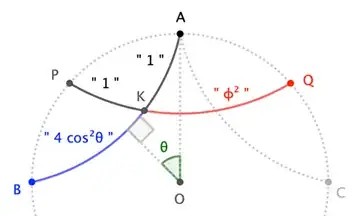

Sides $\overline{AB}$ and $\overline{PQ}$ meet at a point $K$ that divides each of those sides into the ratio $1:\phi$. This construction is "invariant" in Euclidean geometry because all regular pentagrams are similar, and corresponding ratios are preserved by proportionality.

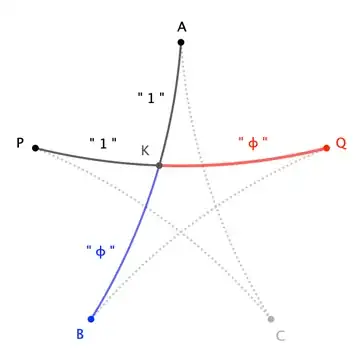

Non-Euclidean geometry lacks similarity: for instance, doubling the lengths sides sharpens the angles of a hyperbolic triangle, and dulls those of a spherical one. So, even if we managed to get a pentagrammic "construction" of the Golden Ratio to work once ...

... we couldn't expect more: larger hyperbolic pentagrams have pointier points (contrariwise for spherical pentagrams), so that the ratio determined by how sides cut each other depends upon scale. Dependence is the antithesis of invariance.

That's not to say, however, that there's nothing to discuss. Indeed, I'm about to launch on a (ahem) lengthy digression ...

In non-Euclidean geometries "raw lengths", and/or ratios thereof, aren't a primary concern in establishing relations in triangles and other figures. Instead, lengths tend to be wrapped in (circular or hyperbolic) trig functions.

Consider, for instance, the Laws of Sines for a $\triangle ABC$ in Euclidean, Spherical, and Hyperbolic planes: $$\frac{a}{\sin A}=\frac{b}{\sin B}=\frac{c}{\sin C} \qquad \frac{\sin a}{\sin A}=\frac{\sin b}{\sin B}=\frac{\sin c}{\sin C} \qquad \frac{\sinh a}{\sin A}=\frac{\sinh b}{\sin B}=\frac{\sinh c}{\sin C} \tag1$$ or the circumference of a circle with radius $r$: $$C_{euc} = 2\pi r \qquad C_{sph} = 2\pi \sin r \qquad C_{hyp} = 2\pi \sinh r \tag2$$ While it is true that the circumference-to-"raw"-radius ratio is not invariant, we can establish $\pi$ (and/or $\tau:=2\pi$) as an invariant "circle constant" by defining it in terms of the ratio of circumference and an appropriate transmutation of radius: $$2\pi = \frac{C_{euc}}{r} = \frac{C_{sph}}{\sin r} =\frac{C_{hyp}}{\sinh r} \tag3$$ Likewise for area: $$\pi = \frac{A_{euc}}{4\left(\tfrac12r\right)^2} = \frac{A_{sph}}{4\sin^2\tfrac12r} = \frac{A_{hyp}}{4\sinh^2\tfrac12r}\tag4$$

Such transmutation is precisely the mechanism that helps us establish the Golden Ratio as a scale-independent —and thus invariant— "pentagram constant" via the above construction, as we can write:

$$\phi = \frac{|KQ|_{euc}}{|PK|_{euc}} = \frac{\sin |KQ|_{sph}}{\sin |PK|_{sph}} = \frac{\sinh|KQ|_{hyp}}{\sinh|PK|_{hyp}} \tag{5}$$ where $|XY|_{geo}$ indicates distance in the corresponding geometry. (I'll omit the subscript when context is clear.)

Importantly, though, this kind of thing doesn't preserve every kind of ratio. In fact, many (most? all?) of the other occurrences of $\phi$ in the Euclidean pentagram don't transfer to non-Euclidean counterparts simply by swapping every length $\ell$ for $\sin \ell$ or $\sinh \ell$.

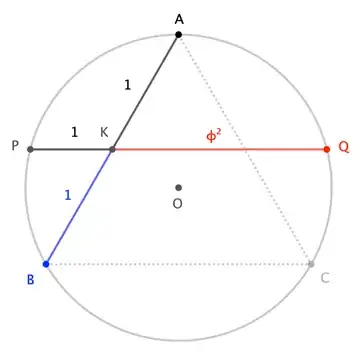

On the other hand, there are other interesting Euclidean occurrences of the Golden Ratio that do have direct non-Euclidean counterparts. For instance, here is a slight restatement of a delightful result from George Odom:

If a midpoint segment of an equilateral triangle is extended to meet the triangle's circumcircle at $P$ and $Q$, then each midpoint divides the extended segment in the square of the Golden Ratio. In particular, for $K$ in the figure, $$\frac{|QK|}{|PK|} = \phi^2 \tag{6}$$

(Odom actually says more-simply that, if $K'$ is the other midpoint, then $$\frac{|KK'|}{|PK|} = \phi \tag{7}$$ a relation equivalent to $(6)$ because $|QK|=|PK|+|KK'|$ and $\phi^2=\phi+1$.)

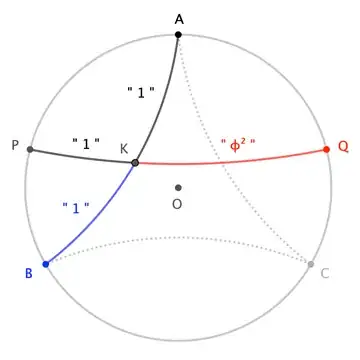

In hyperbolic geometry (spherical is analogous), the same construction "works", provided we apply the "appropriate transmutation" to the lengths:

$$\frac{\sinh|QK|}{\sinh|PK|} = \phi^2 \tag{8}$$

The best we can do for a counterpart to $(7)$ is $$\frac{\sinh|QK|-\sinh|PK|}{\sinh|PK|} = \phi \tag{9}$$ Notice that the numerator does not reduce to $\sinh|KK'|$; as I wrote, the transmutation trick doesn't work for all ratios. (This is why I had to restate Odom's result as a construction of $\phi^2$ instead of $\phi$.)

As a final example where the trick does work (and figures into two aspects of a result), there's this (re-discovered?) generalization of Odom's construction (blog link via trigonography.com):

$$\frac{|BK|}{|AK|} = 4\cos^2\theta \quad\iff\quad \frac{|QK|}{|PK|}=\phi^2 \tag{10}$$ which, eg, in the Hyperbolic plane becomes

$$\frac{\sinh|BK|}{\sinh|AK|} = 4\cos^2\theta \quad\iff\quad \frac{\sinh|QK|}{\sinh|PK|}=\phi^2 \tag{11}$$

I'm going to stop typing now. :)

- 83,939

-

Thank you very much for your answer. It looks like it was a lot of typing. Thank you for that work you did. I have not read it yet, only the first part. How does your answer relate to Pi? I am pretty certain the ratio of the circumference of a circle to its' diameter is dependent on the underlying geometry, and perhaps even on the location in the space. I think the arctic circle and the equator have different ratios to their longitudinal radii of the circles. I think the golden ratio is different than, say 1/2, though I can't say how, yet. I'll read and try to understand what you wrote. – Joe Cash Dec 12 '20 at 20:51

-

On further consideration, I think the difference between 1/2 and Pi or the golden ratio has something to do with relations. I can't explain why 1/2 is a different kind of relation than Pi is yet; but Pi does seem to vary depending on the underlying geometry. – Joe Cash Dec 12 '20 at 20:56

-

Sketch of a proof that the ratio of the circumference of a circle to the diameter of the circle is a different number in non-Euclidean geometries. See the next comment so I have enough room: – Joe Cash Dec 13 '20 at 20:21

-

Consider a ball with unit radius. The surface of the ball, a sphere, provides us with an elliptical (i.e. a non-Euclidean geometry.) Consider the equator of this ball as a circle with center at the north pole. The circumference is equal to two times the Euclidean number we call Pi ~= 3.14159.... The radius, however is equal to Pi/2, so the diameter is Pi. So, circumference / diameter = 2 * Pi / Pi = 2. So, in this geometry, the ratio of the circumference of a circle to the diameter of the circle is 2. – Joe Cash Dec 13 '20 at 20:26

-

Please remember, my motivation for asking the question was: What is invariant across both Euclidean and non-Euclidean geometries. Pi is not invariant. 1/2 seems to be invariant. All numbers may be invariant; so I'm not sure why I think the golden ratio is different than other numbers, yet. I'm not just doing what others have told me to believe in, I am exploring new (granted they are conjectural or even speculative) ideas here. This one, if it pays off, might be consequential. So, even with all the answers, the question remains: what is invariant across Euclidean and non-Euclidean geometries. – Joe Cash Dec 13 '20 at 20:33

-

"Sketch of a proof that the ratio of the circumference of a circle to the diameter of the circle is a different number [...]" Not necessary. Eqn (3) gives formulas; I even write "While it is true that the circumference-to-"raw"-radius ratio is not invariant..." As I say: "raw" lengths aren't a primary concern in non-Euc geometry. Lack of similarity makes ratios of "raw lengths" of non-collinear segments almost-useless. For collinear segments, we work (locally) with the number line (see 1st paragraph); the ambient geometry is irrelevant, so you get "invariance", but it isn't remarkable. – Blue Dec 13 '20 at 21:21

-

I still wanted to present evidence that the ratio of the circumference of a circle to the diameter is not the same in non-Euclidean geometries. In Euclid's Elements, or at least in the first couple of chapters, there is almost no mention of numbers at all; so we don't necessarily work only with the number line. The real motivation for my original post was to find what is invariant across Euclidean and non-Euclidean geometries. I suggested the golden ratio as a candidate. I think invariants are pretty important. So did Einstein. So did Noether. Others do, too. – Joe Cash Dec 14 '20 at 22:19

-

@JoeCash: (Comments aren't for discussion, so this may be my last.) If you're talking about ratios, then you're effectively talking about numbers; if you're talking about ratios of collinear lengths, then you're effectively talking about the number line. Be that as it may ... I appreciate the question, as it inspired me to derive the non-Euclidean Odom result and its extension. (They may well already exist in the literature, but they were new to me. :) So, thanks for that. Cheers! – Blue Dec 14 '20 at 23:50

-

Is there a place for discussion? What is the difference between discussion and what we're doing? I'm glad my question was of some value to you, and thank you for the responses. I have not had a chance to read all your answer; but I intend to, this is just a busy time at work. I hope I can understand everything you wrote. Thanks again. – Joe Cash Dec 16 '20 at 00:16

(This is an addendum to Blue's answer.)

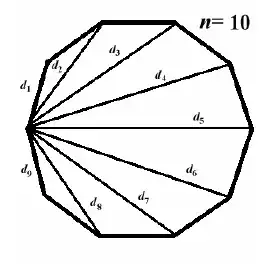

In Blue's answer, the constant $\color{blue}{\phi^2}$ figures prominently . We'll see it is also a diagonal of the decagon with unit side length. (Note: All images are from Antonia Buitrago's 2007 article "Polygons, Diagonals, and the Bronze Mean".)

I. Decagon

We follow Buitrago and define a particular set of diagonals $d_k$ as "a line segment joining a common vertex $v_0$ to vertex $v_k$".

Thus $d_1$ is from $v_0$ to $v_1$, while $d_2$ is from $v_0$ to $v_2$, and so on. Of course $d_1 = d_9$ is just the side length of the decagon. The ratio of $d_k$ to $d_1$ is given by,

$$\frac{d_k}{d_1} = \sqrt{\frac{1-\cos\frac{2\pi k}n}{1-\cos\frac{2\pi}n}} = \frac{\sin\frac{\pi k}n}{\sin\frac{\pi}n}$$

Given a decagon with unit side length $d_1 = 1$, choose the third diagonal, then voila,

$$d_3 = \frac{\sin\frac{3\pi}{10}}{\sin\frac{\pi}{10}} = \color{blue}{\phi^2} \approx 2.61803$$

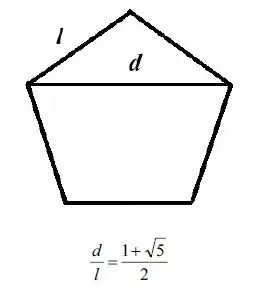

II. Pentagon

For the pentagon with side length $L=d_1=1$, choose the second diagonal,

and we get the well-known appearance of $\phi$ in the pentagon,

$$\frac{d}{L}=\frac{d_2}1 = \frac{\sin\frac{2\pi}{5}}{\sin\frac{\pi}{5}} = \phi \approx 1.61803$$

III. The 13-gon

The tridecagon is slightly more complicated, but that's for another post.

- 60,745