Continuing with giobrach's answer:

We start the simplification by rendering

$\dfrac{1+\cos(\frac{2\pi}{n})}{2}=\cos^2(\frac{\pi}{n})$

So

$R_n=\dfrac{\sin(\frac{2\pi}{n})}{\sqrt{1-\cos^4(\frac{\pi}{n})}-\frac12\sin(\frac{2\pi}{n})}$

We then have

$1-\cos^4(\frac{\pi}{n})=[1+\cos^2(\frac{\pi}{n})][1-\cos^2(\frac{\pi}{n})]=[1+\cos^2(\frac{\pi}{n})]\sin^2(\frac{\pi}{n})$

and

$\sin(\frac{2\pi}{n})=2\sin(\frac{\pi}{n})\cos(\frac{2\pi}{n}),$

from which we can cancel a factor of $\sin(\frac{\pi}{n})$ from the numerator and denominator to get

$R_n=\dfrac{2\cos(\frac{\pi}{n})}{\sqrt{1+\cos^2(\frac{\pi}{n})}-\cos(\frac{\pi}{n})}=[2\cos(\frac{\pi}{n})][\sqrt{1+\cos^2(\frac{\pi}{n})}+\cos(\frac{\pi}{n})]$

This no longer gives the $0/0$ form when $\pi/n\to0$, so a direct substitution leads to

$R_\infty=2+2\sqrt2$

as conjectured.

Both numerical evaluation and Maclaurin series analysis reveal that the truncation term is $O(n^2)$.

Silver and bronze ratios

We generalize the construction in a different way, using nonadjacent sides of some polygons to obtain the silver and bronze ratios.

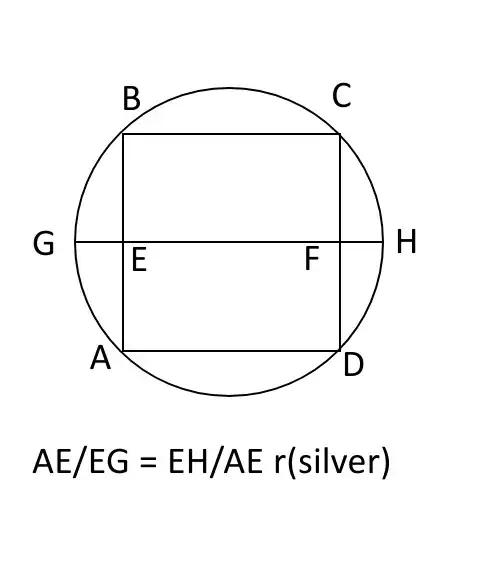

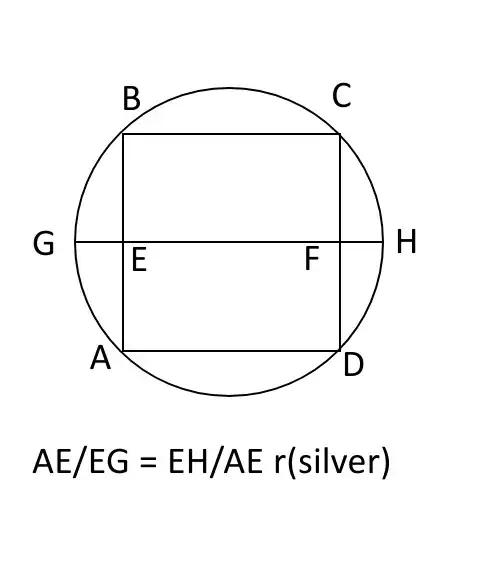

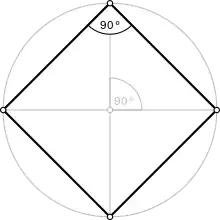

For the silver ratio, begin by inscribing square $ABCD$ in a circle. Construct the chord through the midpoints $E$ of $\overline{AB}$ and $F$ of $\overline{CD}$. This intersects the circle at $G$ nearer to $E$ and $H$ nearer to $F$.

Then the lengths $EG$ and $FH$ are equal, $EF$ is twice $AE$, and $AE$ is the geometric mean between $EG$ and $EH$. These properties guarantee that the ratios $AE/EG$ and $EH/AE$ are both the positive root of $x^2-2x-1=0$, which defines the silver ratio $\sqrt2+1$.

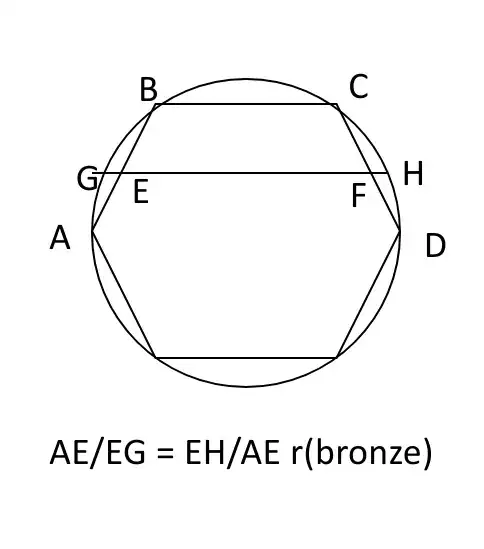

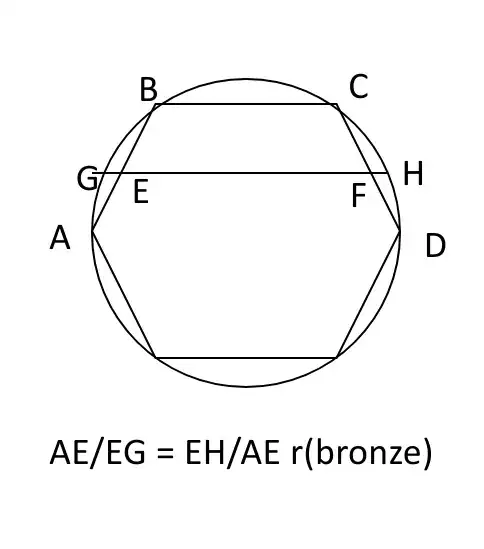

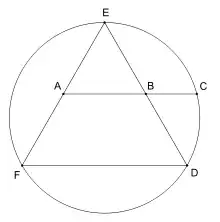

Next, start with a regular hexagon inscribed in a circle. Let $A,B,C,D$ be any four consecutive vertices of the hexagon and then follow the procedure above. This time $EF$ is three times $AE$, so $AE/EG$ and $EH/AE$ satisfy $x^2-3x-1=0$ which defines the brinze ratio $(\sqrt{13}+3)/2$.

$\hskip3.3in$Fig. 1

$\hskip3.3in$Fig. 1 $\hskip3.3in$Fig. 2

$\hskip3.3in$Fig. 2