I'll write proof in probabilistic terminology, which I'm better used too.

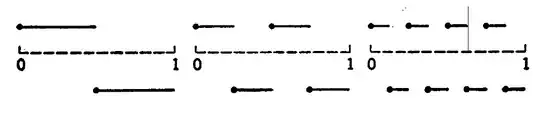

In other words $f = \sum_{j=1}^\infty \frac{Y_j}{2^j}$, where $Y_1,Y_2,..$ are independent, identically distributed random variables (due to product space and measure) with distribution $\lambda(\{\omega : Y_1(\omega)=1 \})=\lambda(\{\omega : Y_1(\omega)=0 \}) = \frac{1}{2}$.

It is obvious that $f \in [0,1]$ everywhere.

First approach

Let $F:\mathbb R \to \mathbb R$ be given by $F(t) = f_*\lambda( (-\infty,t])$. By what we said above, we get $F(t) = 0$ for $t < 0$ and $F(t) = 1$ for $t>1$.

Now, take any $t = \frac{k}{2^n}$ for some $n \in \mathbb N_+$ and $k \in \{1,...,2^n-1\}$ . Such a number has it's binary representation of the form $t = \sum_{i=1}^n \frac{a_i}{2^i}$ (every $a_i \in \{0,1\}$).

We want to compute $F(t) = \lambda (\{\omega : f(\omega) \le t \}) = \lambda (\{ \omega: \sum_{j=1}^\infty \frac{Y_j(\omega)}{2^j} \le \sum_{i=1}^n \frac{a_i}{2^i} \})$

Now, let's say that $1 \le i_1 <...<i_k \le n$ and $a_{i_1},...,a_{i_k} =1$ and the rest are $0$.

We're looking at $i_1$. Clearly, we must have every $Y_1(\omega),...,Y_{i_1-1}(\omega)$ to be equal $0$ (with probability $\frac{1}{2^{i_1-1}}$). Now $2$ cases:

if $Y_{i_1}(\omega)$ is equal $0$ (with probability $\frac{1}{2}$), we can do whatever we want further, since $\sum_{i=i_1+1}^\infty \frac{1}{2^i} = \frac{1}{2^{i_1}}$.

if $Y_{i_1}(\omega) = 1$ (with probability $\frac{1}{2}$), then we must have every $Y_{i_1+1}(\omega),...,Y_{i_2-1}(\omega)$ to be equal $0$ (with probability $\frac{1}{2^{i_2-i_1-1}}$) and now, again for $Y_{i_2}$ we have two cases (similarly, either it is $0$ and we can do whatever we want further, or it's $1$, and we need some more (if any) to be $0$, and so on till $Y_{i_k}$.

To sum up together, we get $$F(t) = \frac{1}{2^{i_1}} + \frac{1}{2^{i_1}}\cdot \frac{1}{2^{i_2-i_1}} + ... + \frac{1}{2^{i_{k-1}}}\cdot \frac{1}{2^{i_k - i_{k-1}}} = \sum_{j=1}^k \frac{1}{2^{i_k}} = \sum_{i=1}^n \frac{a_i}{2^i} = t$$

We showed the result for dyadic $t$, but by density of such dyadics in $[0,1]$ and right continuity of $F$ (due to continuity of finite/probabilistic measure), we get for any $t \in [0,1] : F(t) = t$.

Now, since CDF of a random variable uniquelly describes the distribution, we get that $f$ is a random variable with uniform distribution, hence $\lambda_*f(E) = m(E \cap [0,1])$, where $m$ is Leb.Measure

(Or you can proceed without referring to probability. We get $\lambda_*f( (-\infty,t]) = t 1_{t \in [0,1]} + 1_{t \in (1,+\infty)}$, so that $\lambda_*f( (a,b]) = 1_{b > 1} + b1_{b \in [0,1]} - 1_{a>1} - a_{a \in [0,1]}$ so again, since such intervals generate borel sets, we get $\lambda_*f(E) = m(E \cap [0,1])$

Second approach

Using notion of characteristic function, we can do it even simplier. CF of a random variable $f$ is given by $\varphi_f:\mathbb R \to \mathbb C$, $\varphi_f(t) = \mathbb E[\exp(itf)] = \int_{\Omega} \exp(itf(\omega))d\lambda(\omega)$. Letting $g=2f-1 = \sum_{j=1}^\infty \frac{2Y_j - 1}{2^j}$ we get by independence and dominated convergence

$$ \varphi_g(t) = \mathbb E [ \prod_{j=1}^\infty \exp(i \frac{t}{2^j} (2Y_j-1)) ] = \prod_{j=1}^\infty \varphi_{2Y_j-1}(\frac{t}{2^j})$$

We can easily calculate $\varphi_{2Y_j-1}(s) = \frac{1}{2}(e^{is} + e^{-is}) = \cos(s)$ so that for $t \neq 0$ we get$$\varphi_g(t) = \lim_{ M \to \infty} \prod_{j=1}^M \cos(\frac{t}{2^j}) = \lim_{M \to \infty} \prod_{j=1}^M \sin(\frac{t}{2^{j-1}}) \frac{1}{2 \sin(\frac{t}{2^j})} = \lim_{M \to \infty} \sin(t) \frac{\frac{1}{2^M}}{\sin(\frac{t}{2^M})} \to \frac{\sin(t)}{t}$$

Which means that $g$ has Uniform $[-1,1]$ distribution, hence $f=\frac{g+1}{2}$ has Uniform $[0,1]$ distribution, and we get the same result