OK, so me and my friend are working on a problem in which you do the opposite to trying to stuff as many of the I shape tetrominoes in a square as possible. Trying to find the smallest number of I shape tetrominoes that you have to place in the square such that another I shaped tetromino cannot be placed in the square.

So I define $I_n$ to be the sequence such that the rules of the above problem are satisfied.

My friend made a program that finds the values of this sequence. So far we have found that

$I_1 = 0, \ I_2 = 0, \ I_3 = 0, \ I_4 = 4, \ I_5 = 4, \ I_6 = 6, \ I_7 = 7, \ I_8 = 9.$

The problem is that we have got no proofs for any of the cases where $n > 4$.

At first I tried using the pigeonhole principle to try to prove a few cases. For example, when $n = 5$ my argument went a little bit like this.

Lets assume WLOG that an I shaped tetromino was placed in the first row of the square and that a second I shaped tetromino was placed in another row. Now we just place the third shape in the suquare, then that means that there are $5*5 - 4*3 = 13$ remaining free squares. Now using the pigeonhole principle and the assumption of the placement of the first 2 shapes we we get that $13 - 2 = 11$ of the squares are distributed on the 3 rows in which the first $2$ I shapes were not placed. Now by the pigeonhole principle we get that one of the rows must have $\lceil{\frac{11}{3}}\rceil = 4$ free squares. And this is the point where the proof breaks down. I neglected the fact that you can place other I shapes such that even if the row has 4 free squares you still cannot place a new I shape tetromino in it.

So I ask anyone if they have any good ideas that can progress our investigation.

P.S. If you have proofs for your assertions, then please write them out :)

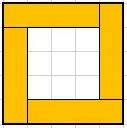

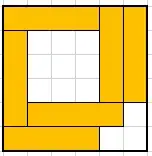

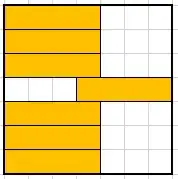

Here I have added visual examples starting from $n = 5$:

$n = 5$

$n = 6$

$n = 7$

$n = 8$

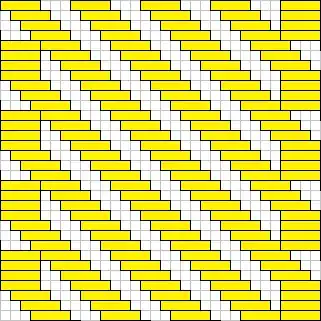

I and my friend are also looking into the same problem with square tetrominoes. I have a general formula for the squares: $\lceil\frac{n-1}{3}\rceil^2$.

My proof starts off by showing how we can do a minimal covering of a $5\times n$ rectangle.

We notice that if we always put new squares in such that they are one cell away from the boundaries of the rectangle and from each other, then looking through a few cases we can come to the conclusion that the formula is $\lceil\frac{n-1}{3}\rceil$.

Now the same principe of being one cell apart from everything else when it can be done also applies for the $n\times n$ case. So then the smallest count would be attained by a certain configuration (I called it the perfect configuration) of the squares. Now it is not hard to notice that the number of squares in the $n \times n$ case is simply the square of the $5 \times n$ case.

My proof basically went along the lines that if you try to remove a square or displace it from the position in which it would be in the perfect configuration, then you could always add a new square, thus gaining a covering that takes up more squares then the perfect configuration one so, therefore the perfect configuration covering must be the minimal.

P.S. If anyone knows any good sources or literature concerning this topic, then please do share them. Thank you!