This question is rephrased as a game and can be analyzed with no computation!

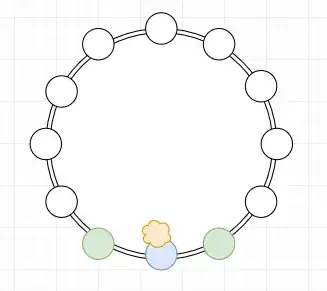

A class of 30 children is playing a game where they all stand in a

circle along with their teacher. The teacher is holding two things: a

coin and a potato. The game progresses like this: The teacher tosses

the coin. Whoever holds the potato passes it to the left if the coin

comes up heads and to the right if the coin comes up tails. The game

ends when every child except one has held the potato, and the one who

hasn't is declared the winner.

How do a child's chances of winning change depending on where they are

in the circle? In other words, what is each child's win probability?

From FiveThirtyEight Puzzle Column

It is equivalent to show that all students have equal probability of winning. To this end, consider the students to the left and the right of the teacher. Call them the teacher's pets. Both teacher's pets have equal probability of winning by symmetry.

Diagram 1: The teacher is blue, the teacher's pets are green, and the potato is a lumpy yellow cloud. Small white circles are the other students.

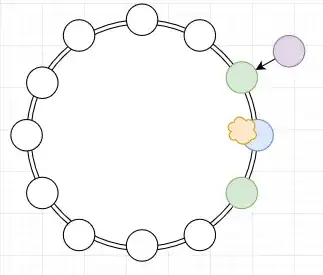

Now consider any student who hasn't lost yet. We can show he has the same chance of winning as a teacher's pet. Call this student "Purple".

Diagram 2: Purple is a student who hasn't lost yet.

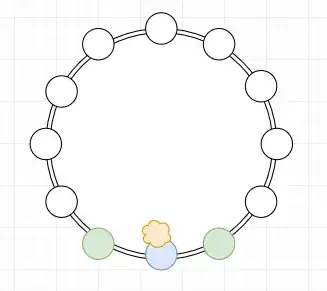

With $100 \%$ certainty, the potato will arrive to Purple's left or to his right eventually. Consider the first time this happens.

Diagram 3: The potato touches one of his neighbors for the first time. Red players have lost already.

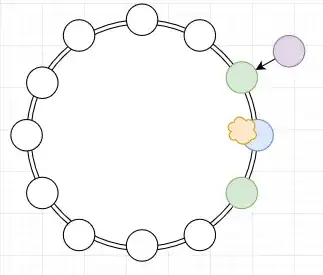

In that situation, he use the power of imagination! He can image that he himself is a teacher's pet since his situation has become identical to the starting condition, and therefore his probability of winning is the same as that of the teacher's pets.

Diagram 4: Purple imagines that he is a teacher's pet. The arrow should be understood to mean "imagines himself as".