Stephen Abbott. Understanding Analysis (2016 2 edn). p. 55. Not a duplicate.

Exercise 2.3.11 (Cesaro Means). (a) Show if $\{x_n\}$ is a convergent sequence, then the sequences given by the averages $\{\dfrac{x_1 + x_2 + ... + x_n}{n}\}$ converges to the same limit. (Not a duplicate)

I rewrote and colored the official solution.

Let $\epsilon>0$ be arbitrary. Then we need to find an $N \in \mathbb{N} \qquad \ni n \geq N \implies\ |\frac{x_1 + x_2 + ... + x_n}{n} - L|< \epsilon \tag{1}$.

Question posits $(x_{n}) \to L$. So $\exists \; M \in \mathbb{N} \ni n \ge M \implies |x_{n}-L|< M \quad (2)$.

$\text{Also } \exists \; C \ni n \ge C \implies |x_{n}-L|< \epsilon/2. \quad \tag{3}$

My question 1. Where does (3) issue from? How to presage $\epsilon/2$? Normally you start with $\epsilon$.

Doesn't the same argument prove all the terms can be bounded? Why simply 'the early terms in the averages can be bounded' ? Please expatiate on "Because the original sequence is convergent, we suspect that we can bound ... we will be breaking the limit in two at the end" ?

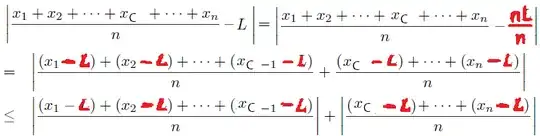

I still don't understand how "we suspect" these bounds?Now for all $n \ge C$, we can write

How to presage rewriting $\color{red}{L = nL/n}?$

How to presage spltting the sum between $x_{C - 1}$ and $x_C$?

Now apply the Triangle Inequality to each of the $n$ $(x_i - L)$ terms.

$\begin{align} \le & \frac{1}{n}( & \color{green}{\left| x_{1}-L\right| +\ldots +\left| x_{c-1}-L\right|} & + \color{brown}{\left| x_{C}-L\right| +\ldots +\left| x_{n}-L\right|} & )\\ & & \color{green}{\text{Each of these $(C - 1)$ terms < M by (2)} } & \color{brown}{ \text{ Each of these $(n - C)$ terms < $\epsilon/2$ by (3)}} & \\ \le & \frac{1}{n}( & \color{green}{(C - 1)M} & + \color{brown}{\frac{e}{2}(n - C)} & ). \tag{4}\\ \end{align}$

Why is the last inequality (4) above $\le$? Why not $<$ like (2) and (3)?

Because C and M are fixed constants at this point, we may choose $N_2$ so that $\color{green}{(C - 1)M}\frac{1}{n} < e/2 \tag{5}$ for all $n \ge N_2$. Finally, let $N$ [in $(1)$] $= \max\{C, N_2\}$ be the desired $N$.

Why are we allowed to choose $N_2$ so that $\color{green}{(C - 1)M}\frac{1}{n} < e/2$?

$C \in \mathbb{N} \quad \therefore n - C < n \iff \color{magenta}{\frac{n - C}{n}} < 1 \tag{6}$

$\begin{align} \text{Equation (4) is} & & \color{green}{(C - 1)M}\frac{1}{n} & + \frac{e}{2}\color{magenta}{\frac{n - C}{n}}. \\ \text{Then by (5) and (6),} & & < e/2 & + e/2\color{magenta}{(1)}/ QED. \\ \end{align}$