Complex numbers make 2D analytic geometry significantly simpler.

The discovery of analytic geometry dates back to the 17th century, when René Descartes (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ren%C3%A9_Descartes) came up with the genial idea of assigning coordinates to points in the plane. Now it seems almost trivial, but this was a huge leap for mathematics: it connected two previously separate areas. Suddenly, you could do geometry by doing calculations with numbers!

Getting a new point of view like this one is *huge *and it usually leads to lots of new interesting results: because now you can use a new, better language that allows you to *think *about new concepts in an easier way.

Example: There were many open problems in ancient Greek geometry. Among them, Angle trisection (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trisection), Squaring the circle (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Squaring_the_circle), and Doubling the cube (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Doubling_the_cube). All of these are impossible when using just a compass and a straightedge. These problems were open for centuries because there is basically no way you can prove that they cannot be solved, just by thinking in terms of geometry. We needed algebra. Once we started studying the algebraic properties of geometric constructions, we discovered, for example, that all lengths constructible using a compass and a straigthedge are algebraic numbers such that the degree of their minimal polynomial is a power of 2. This, among other things, rules out the constructibility of $\sqrt[3]{2}$.

Now, analytic geometry gave us a nice new tool that was easy to work with -- as long as you dealt with points and linear objects only. Checking whether two lines are parallel? Easy. Finding the intersection of two line segments? Easy. Rotating an object around a point? Possible, but painful. Once you start dealing with angles and rotations, the notation starts to be really clumsy. Part of the reason is that you have to work with each coordinate separately, and you don't really see the connections between the coordinates and the angles.

This all changed once we realized that the Complex plane (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Complex_plane) is isomorphic to the standard Cartesian plane. Thus, when doing analytic geometry in 2D, instead of representing a point by a pair of reals, we can represent it by a single complex number. Instant profit!

Why? Because for complex numbers we have the polar form (see Complex number (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Complex_numbers#Polar_form)) and we have a very good idea how they relate to angles: namely, when you multiply two complex numbers, you multiply their sizes (absolute values) and add their polar angles (arguments). When doing 2D analytic geometry using complex numbers, operations that involve angles and rotations become as simple as translations and resizing.

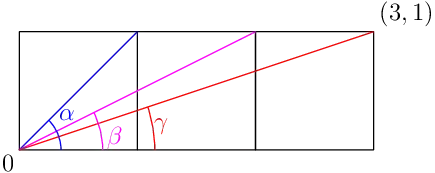

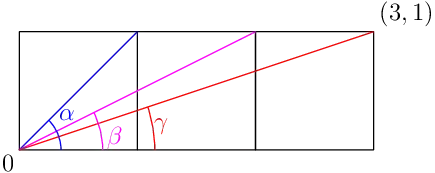

Here's one nice example. Go ahead and try solving it without complex numbers, before reading the solution. The question is simple: what is the sum of the three angles shown in the picture?

Here's the answer: The three angles correspond to the complex numbers $1+i$, $2+i$, and $3+i$. To add those three angles together, we simply multiply those three numbers. We get:

$(1+i)(2+i)(3+i) = 10i$.

Hence, the sum of those three angles is precisely the right angle. Neat, right?