I am an elementary school teacher from South Korea who previously posted a question titled "a new Pythagorean proof here" I have gathered the answers from that question along with my own research to formulate a new set of questions (summarized in a paper I am working on here). I would like to ask for your opinion on the validity of these questions.

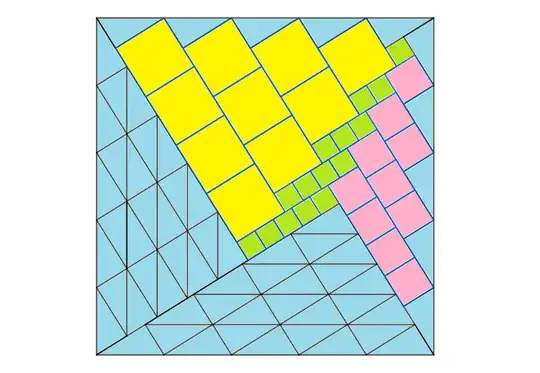

I am considering a problem that generalizes the dissection proof of the Pythagorean theorem: tiling an $nc \times nc$ square with a specific set of tiles for any natural number $n$. I have established what I believe to be a complete theoretical framework for this problem and would like to inquire about its validity. Problem Setup Goal: To perfectly tile an $nc \times nc$ square. Assumption: For a given right triangle $T_{a,b}$, its two legs, $a$ and $b$, are linearly independent over $\mathbb{Q}$ (i.e., $a/b$ is not a rational number). The length of the hypotenuse is $c = \sqrt{a^2 + b^2}$. Tile Set: The set of available tiles, $\mathcal{T}$, consists of the following four types:

$T_{a,b}$: A right triangle with base $a$ and height $b$. $S_a$: A square with side length $a$. $S_b$: A square with side length $b$. $S_{|a-b|}$: A square with side length $|a-b|$.

Core Question Is the following necessary and sufficient condition, along with its proof, valid? I propose that a tiling of the $nc \times nc$ square exists if and only if there is a non-negative integer solution $(N_a, N_b, N_T, k)$ that satisfies both of the following algebraic and combinatorial conditions. Here, $N_x$ represents the number of tiles of type $S_x$ or $T_x$, and specifically, $k = N_{|a-b|}$ is the number of "core tiles" $S_{|a-b|}$.

Algebraic Condition:

\begin{align}N_a + k &= n^2 \\ N_b + k &= n^2 \\ N_T &= 4k \end{align}

Combinatorial Condition:

$$k \geq n$$

I would appreciate a review of the rigor and completeness of the logical structure presented below to prove this proposition.

Proof Outline

1. Proof of Necessity ($\Rightarrow$)

Assumption: A valid tiling exists.

Derivation of the Algebraic Condition: We equate the total area of the $nc \times nc$ square, which is $n^2c^2 = n^2(a^2 + b^2)$, with the sum of the areas of all tiles used:

$$N_a a^2 + N_b b^2 + N_T \left(\frac{1}{2}ab\right) + k(a-b)^2$$

By expanding $(a-b)^2$ and rearranging, we get:

$$n^2a^2 + n^2b^2 = (N_a + k)a^2 + (N_b + k)b^2 + \left(\frac{N_T}{2} - 2k\right)ab$$

Since $a$ and $b$ are $\mathbb{Q}$-linearly independent, the terms $a^2$, $b^2$, and $ab$ are also linearly independent over $\mathbb{Q}$. By comparing the coefficients, the three algebraic equations are necessarily derived.

Derivation of the Combinatorial Condition ($k \geq n$): We consider the entire $nc \times nc$ square as an $n \times n$ grid of $c \times c$ cells. For structural integrity, each row and each column must contain at least one "core tile" ($S_{|a-b|}$). The minimum number of core tiles required to cover all $n$ rows and $n$ columns is $n$ (for example, by placing $n$ tiles along the main diagonal). Therefore, it must be that $k \geq n$.

2. Proof of Sufficiency ($\Leftarrow$)

Assumption: There exists an integer $k$ (where $n \leq k \leq n^2$) that satisfies both the algebraic and combinatorial conditions.

Constructive Proof using Mathematical Induction on $k$:

Base Case ($k = n$): I have demonstrated through a specific algorithm called "spiral dissection" that a geometric construction of the tiling is always possible for any natural number $n$ when $k = n$. This algorithm places the $n$ core tiles $S_{|a-b|}$ on the main diagonal and fills the remaining space with the other tiles.

Inductive Step ($m \rightarrow m+1$): Assume that for some integer $m$ such that $n \leq m < n^2$, a valid tiling $T_m$ with $k = m$ exists. Because $m < n^2$, the algebraic conditions imply $N_a = n^2 - m > 0$ and $N_b = n^2 - m > 0$. Therefore, the tiling $T_m$ must contain at least one $S_a$ tile and at least one $S_b$ tile.

A $c \times c$ area can be tiled by either a "simple module" consisting of $\{$one $S_a$, one $S_b\}$ or a "core module" consisting of $\{$one $S_{|a-b|}$, four $T_{a,b}\}$. Both modules have the same total area of $a^2 + b^2 = c^2$.

We find one "simple module" in the tiling $T_m$ and perform a local substitution with a "core module." This geometric transformation results in a new tiling $T_{m+1}$ that precisely satisfies the algebraic conditions for $k+1$:

- $k$ increases by 1 ($k \rightarrow k+1$).

- $N_a$ and $N_b$ decrease by 1.

- $N_T$ increases by 4.

Conclusion: Through this inductive process, we can construct the solutions for $k = n+1, n+2, \ldots, n^2$ starting from the base solution where $k = n$. Therefore, a tiling exists for every value of $k$ that satisfies the conditions.

Thus, could my overall approach—(1) specifying certain conditions as necessary and sufficient, and (2) proving their necessity through algebraic/combinatorial arguments and their sufficiency through constructive induction—be considered a valid theoretical framework for perfectly explaining the existence of solutions to this generalized Pythagorean proof problem?