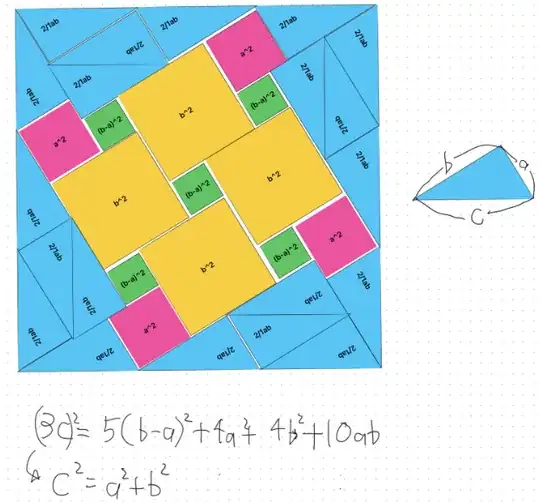

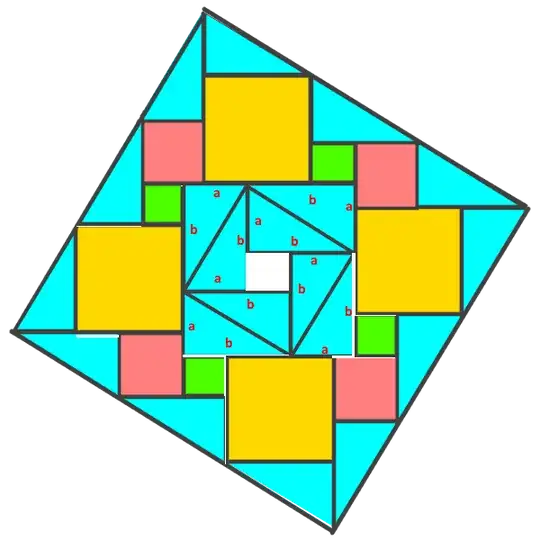

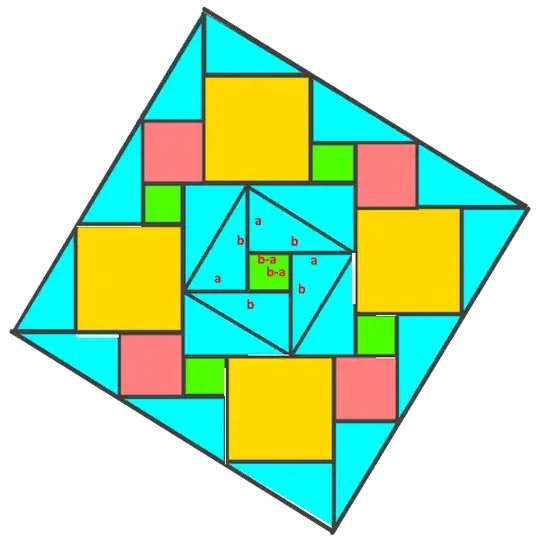

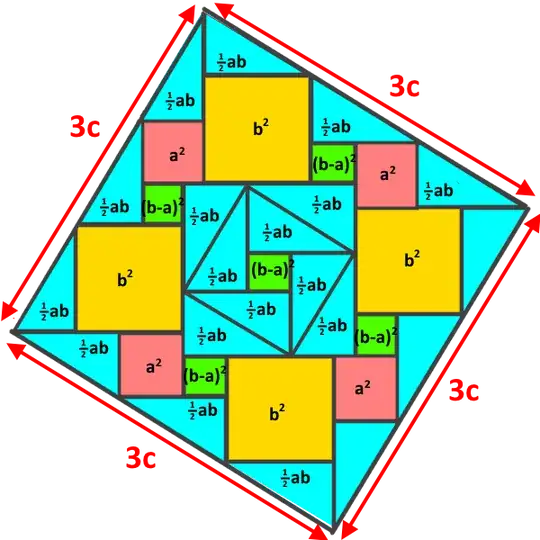

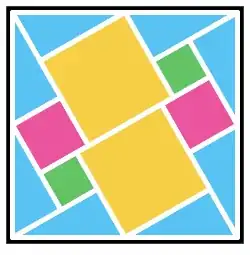

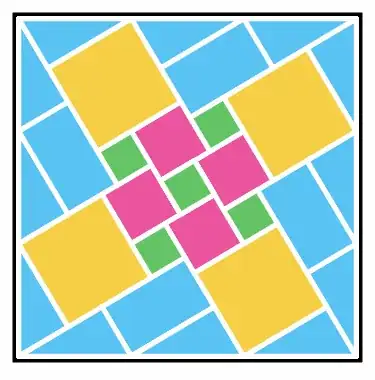

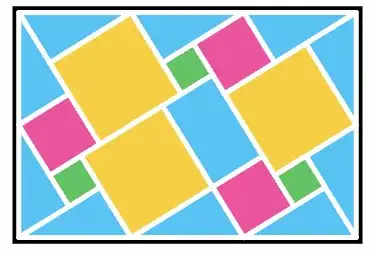

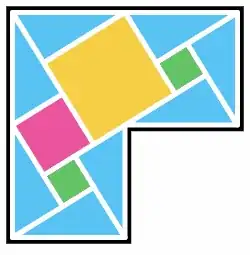

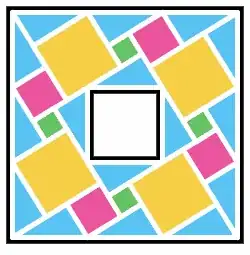

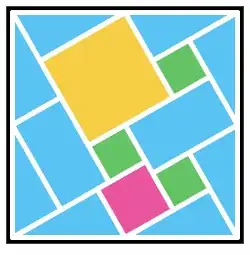

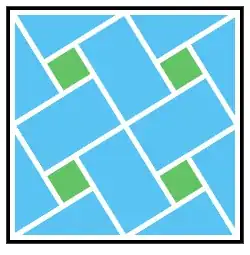

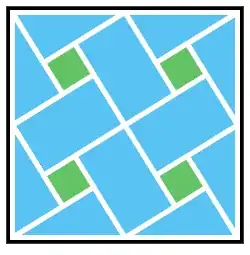

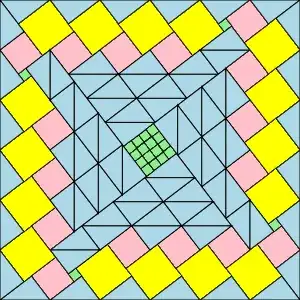

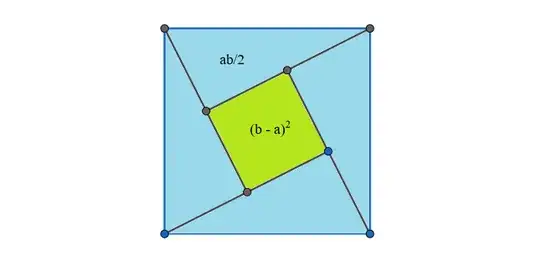

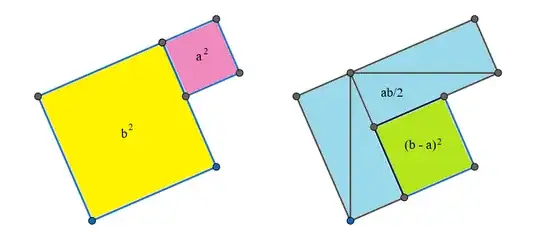

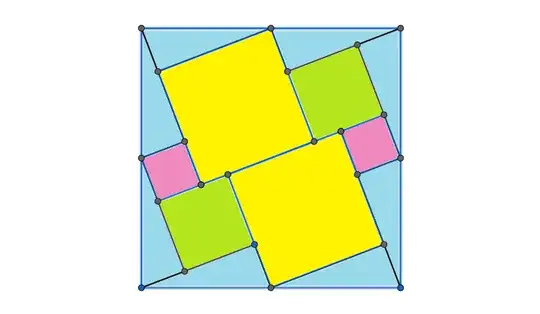

I am writing to you today because I believe I may have developed a new visual proof for the Pythagorean theorem. The proof is based on a geometric dissection method, equating the area of a larger composite square to the sum of its smaller constituent parts. I have attached an image file containing a diagram of the proof and the corresponding algebraic derivation.

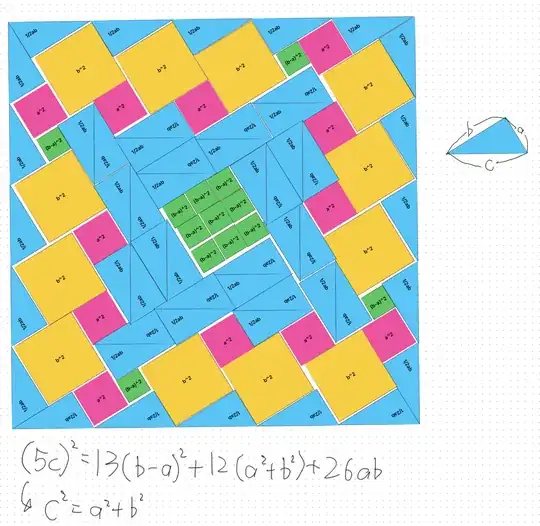

The core of my derivation is that the area of the large square, which I represent as $(3c)^2$, is equal to the sum of the areas of the internal shapes: $5(b-a)^2 + 4a^2 + 4b^2 + 10ab$. This equation simplifies to the well-known Pythagorean identity, $c^2 = a^2 + b^2$. I am aware that there are hundreds of documented proofs of this theorem. However, I have not been able to find this specific dissection arrangement in my research.

Could you possibly spare a moment to review my work? I would be deeply grateful for your professional opinion on whether this proof is, to your knowledge, a novel discovery or a variation of a known proof. Thank you for your time and consideration.

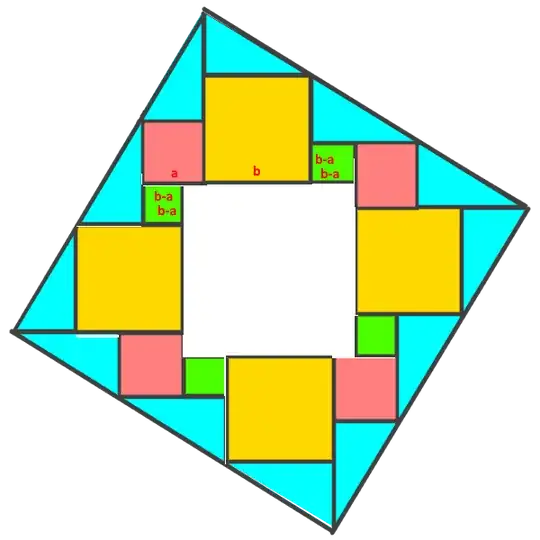

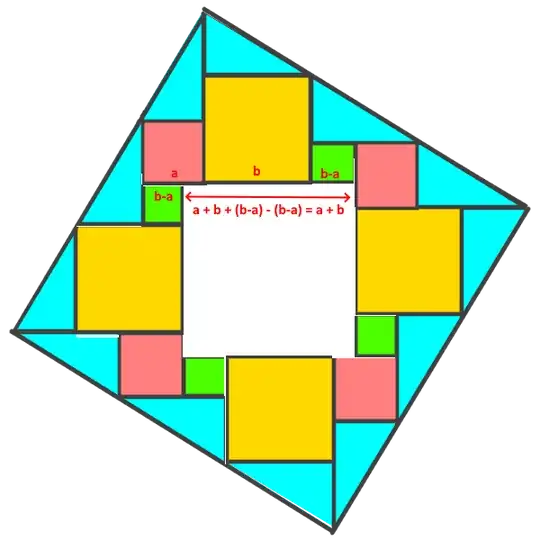

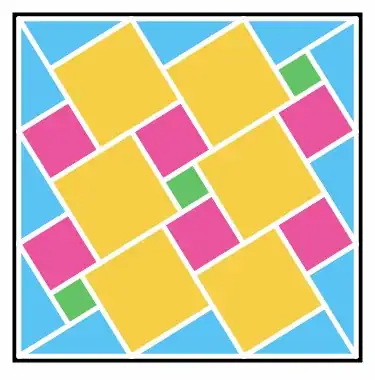

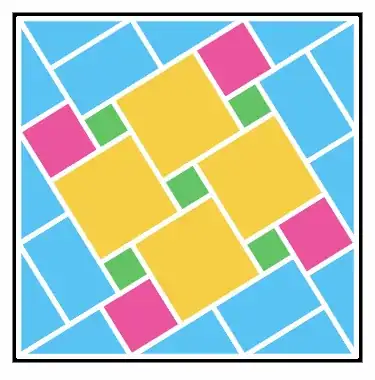

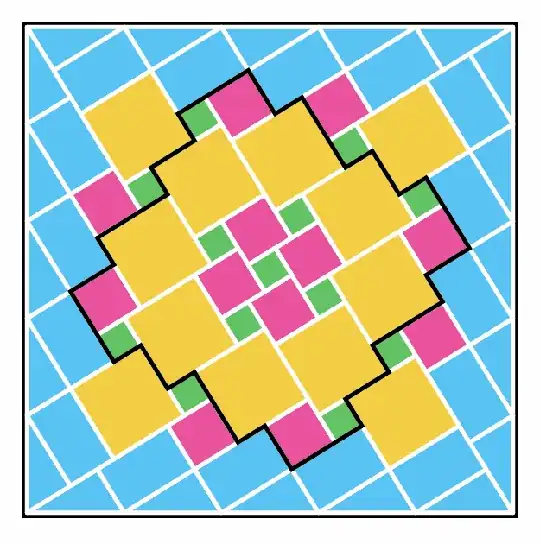

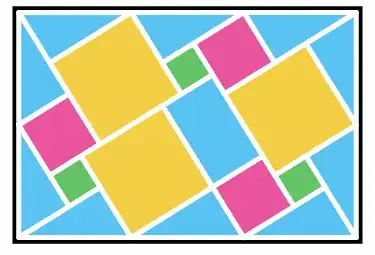

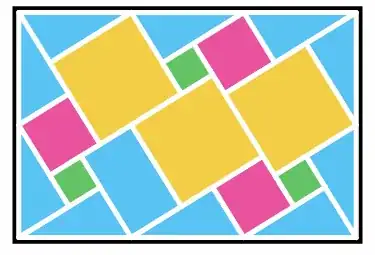

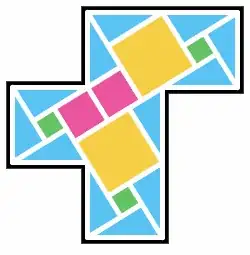

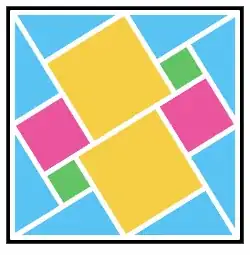

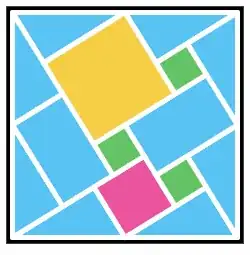

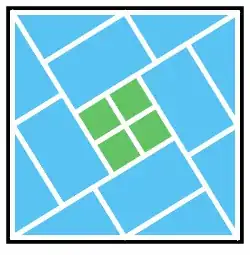

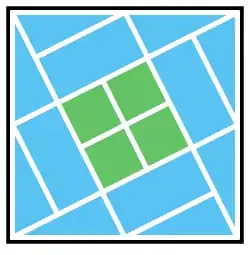

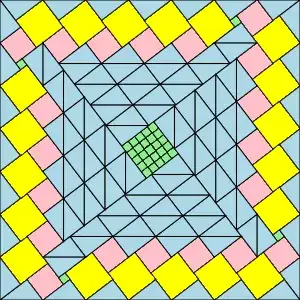

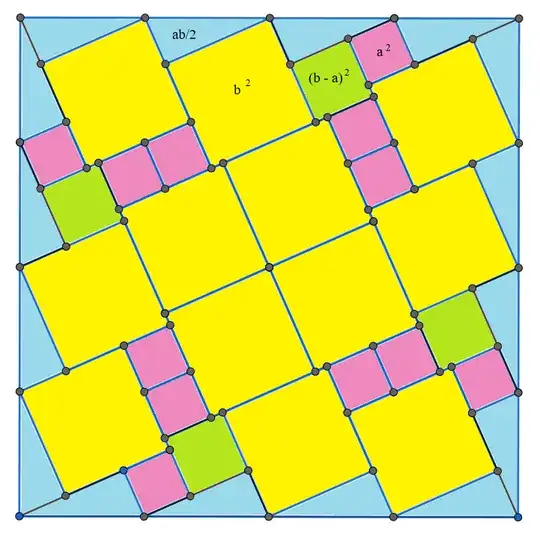

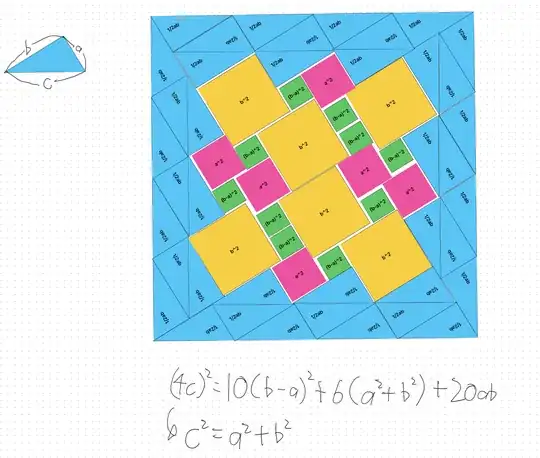

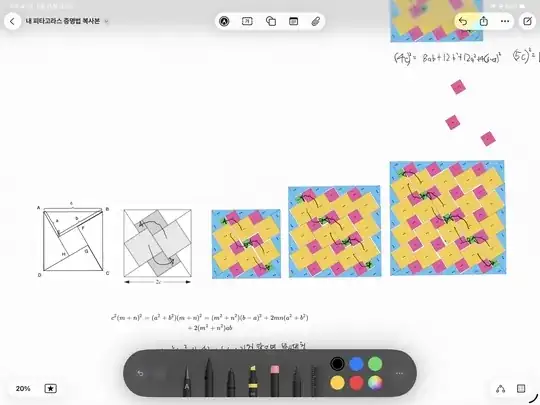

*plus: I have recently been working on geometric proofs of the Pythagorean theorem. Following my recent development of a proof via a "$3c$ side" dissection, I have extended my research and believe I have established a unique dissection for a "$4c$ side" scenario.

I have consolidated my findings and was hoping you might be able to offer your expert assessment. Could you please let me know if you believe this proof is both valid and original? I would be very grateful for your feedback.

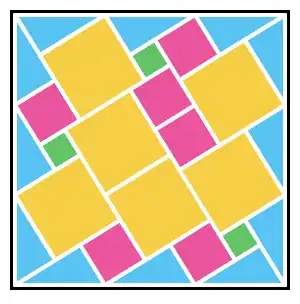

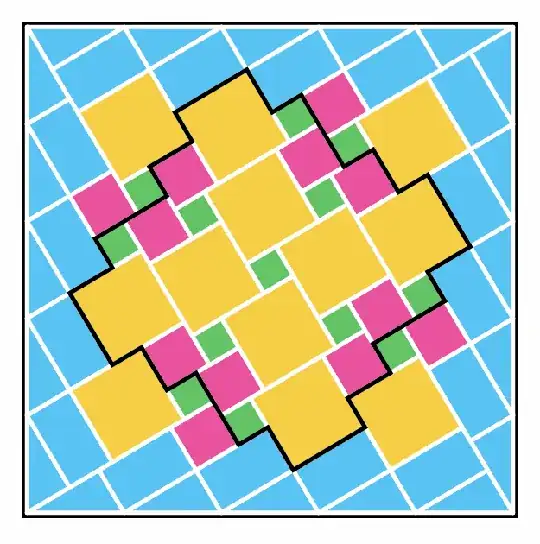

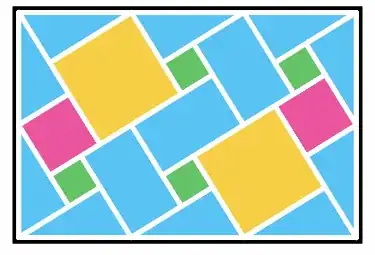

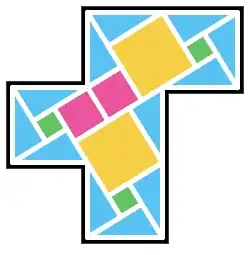

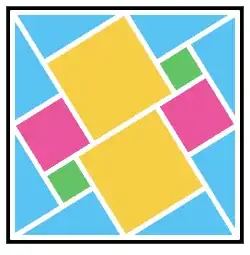

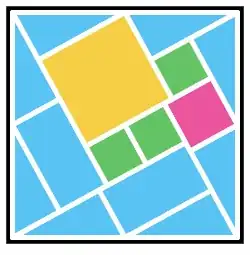

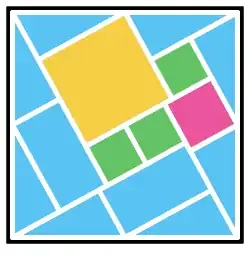

plus: I make $5c$ and new $3c$ too

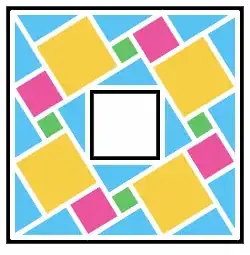

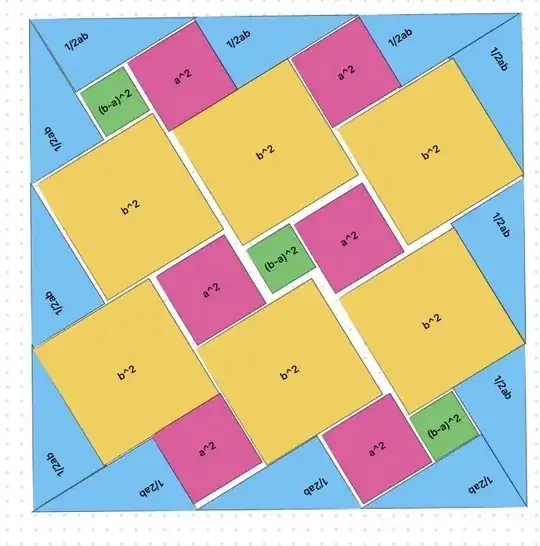

Building on these findings, I am led to conjecture that an infinite series of such proofs might exist. It seems plausible that this method could be generalized for a hypotenuse corresponding to n units (where $n = 3, 4, 5, ...$), thus creating a potentially limitless set of proofs. As many of you in the comments have mentioned, the equation

$$c^2(m + n)^2 = (a^2 + b^2)(m + n)^2 = (m^2+n^2)(b-a)^2+2mn(a^2+b^2)+2(m^2+n^2)ab$$

appears to be valid, suggesting that an infinite number of proofs could be constructed from it. My friend Ko and I have analyzed the proof methods, and we hypothesize that all the figures exhibit point symmetry.

Building on these findings, I am led to conjecture that an infinite series of such proofs might exist. It seems plausible that this method could be generalized for a hypotenuse corresponding to n units (where $n = 3, 4, 5, ...$), thus creating a potentially limitless set of proofs. As many of you in the comments have mentioned, the equation

$$c^2(m + n)^2 = (a^2 + b^2)(m + n)^2 = (m^2+n^2)(b-a)^2+2mn(a^2+b^2)+2(m^2+n^2)ab$$

appears to be valid, suggesting that an infinite number of proofs could be constructed from it. My friend Ko and I have analyzed the proof methods, and we hypothesize that all the figures exhibit point symmetry.

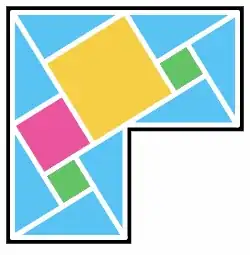

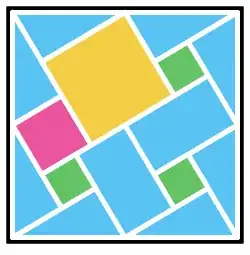

P.S. I was excited to discover a general method for completing n x n composition patterns. It turns out the solution is to form a diagonal chain, as indicated by the black arrows in the diagram. I was genuinely surprised to have figured this out myself! This proof is conjectured to be special in that it requires the minimum number of triangles for an nc-tiling. This proof method I've developed operates based on the following equation(as @Blue mentioned):"

\begin{align}(nc)^2&=n(n-1)(a^2+b^2)+n(a-b)^2+4n\cdot\tfrac12ab\\&=n^2(a^2+b^2)+n\left(-(a^2+b^2)+(a^2+b^2-2ab)+2ab\right)\\&=n^2(a^2+b^2)\end{align}

My conjecture is that when tiling a square with a side length of nc (where c is the hypotenuse), if n is a prime number, then this method is the unique way to create no more than the minimum of 4n triangles.

I have some research questions that I'm curious about but can't pursue myself, as I'm not a mathematician.

Regarding the aforementioned "$nc$ tiling," it has been proven that at least one tiling method exists where the number of triangles is minimized as '$n$' approaches infinity. However, I wonder:

Could we determine the number of tiling methods for a specific '$n$'? How many other tiling methods are there? As '$n$' approaches infinity, does the number of these methods also approach infinity? If so, what is the rate at which it approaches infinity? Based on my limited knowledge, it seems like these questions might be provable using series and analytical methods.

and I am an elementary school teacher in Korea, and as mathematics is not my primary field, I am unsure whether these findings warrant publication. If they do, I would greatly appreciate guidance on the process.