I recently took a look at this pretty interesting question about solving a logarithmic equation without calculus: Find all real solutions of $\log_2 x + \log_x 9 = \log_2 (x+9)$ without using derivatives

Here's the question: can we solve $$\log_2(x)+\log_x(n)=\log_2(x+n)$$ for a solution in terms of elementary functions, as a closed form or as an infinite sum? Unless $n=1$ (where this has no solutions), $x=n$ is always a solution, because if $x=n$ then we have $$\log_2(n)+\log_n(n)=\log_2(2n) \Rightarrow \log_2(n)+1=\log_2(n)+1$$ For $n<1$, $x=n$ is the only solution, but for $n>1$ there's always a mysterious second solution... how do we find it?

Bonus: it looks like $n=9$ (and actually $n=4$, which is the only $n>1$ with one solution, as noted by @PavanC.) is somehow the only integer with an integer second solution. $2,5,$ even other powers of $3$ all have very sketchy second solutions. Would be cool to prove.

I broke $\log_x(n)$ into $\log_x(2)\log_2(n)$ to get $$\log_2(x)+\log_2(n)\frac{1}{\log_2(x)}=\log_2(x+n)$$ and raised $2$ to both sides, which gave me $$xn^{\log_x(2)}=x+n \Rightarrow n^{\log_x(2)}=1+\frac{n}{x} \Rightarrow n=\left(1+\frac{n}{x}\right)^{\log_2(x)}?$$ So then I try to substitute that into the $n$ on the right-hand side, which gives me $$n^{\log_x(2)}=1+\frac{1}{x}\left(1+\frac{n}{x}\right)^{\log_2(x)}$$ Ehh... So I tried another solution that would at least help me visualize this in Desmos, something of the form $f(x)=g(n)$. But looking for one only led me back and back again to the pathetically simple $$x(n^{\log_x(2)}-1)=n$$ which doesn't even work. I tried once again to use the log base conversion, which gave $$x(2^{\log_x(n)}-1)=n \Rightarrow x=\frac{n}{2^{\log_x(n)}-1}$$ but I can't get rid of the logarithm with base $x$! For my last desperate attempt, I took the original equation and multiplied both sides by $\log_2(x)$ to obtain $$\log_2(x)^2-\log_2(x+n)\log_2(x)+\log_2(n)=0$$ which looked like a funny quadratic equation of $\log_2(x)$? I then attempted a substitution of $y=\log_2(x)$, which would've implied $x=2^y$, but that didn't go over too well with the $\log_2(x+n)$. I imprudently proceeded with the quadratic procedure anyway, setting $$\log_2(x)=\frac{\log_2(x+n)\pm \sqrt{\log_2(x+n)^2-4\log_2(n)}}{2}$$ I was then at least a little enthusiastic, because maybe I could express the whole thing in terms of $\log_2(x+n)$? But wouldn't you know it, if I set $z=\log_2(x+n)$, I got $$\frac{z \pm \sqrt{z^2-4\log_2(n)}}{2}+\log_2(n)\frac{2}{z\pm \sqrt{z^2-4\log_2(n)}}=z$$ I reluctantly multiplied both sides by $z\pm \sqrt{z^2-4\log_2(n)}$, which gave me $$\frac{1}{2}\left(2z^2-4\log_2(n)\pm 2z\sqrt{z^2-4\log_2(n)}\right)+2\log_2(n)=z^2\pm \sqrt{z^2-4\log_2(n)}$$ A light at the end of the tunnel??? I saw the opportunity to cancel $z^2$ and $2z\sqrt{z^2-4\log_2(n)}$, and so I took it and got $$z^2-2\log_2(n)\pm z\sqrt{z^2-4\log_2(n)}+2\log_2(n)=z^2 \pm \sqrt{z^2-4\log_2(n)} \Rightarrow -2\log_2(n)+2\log_2(n)=0 \Rightarrow 0=0$$ ...oh.

I'm all out of ideas now, what do I do? And, are there any interesting properties of the solution to this equation (that is not $x=n$) that we can prove for certain constraints on $n$?

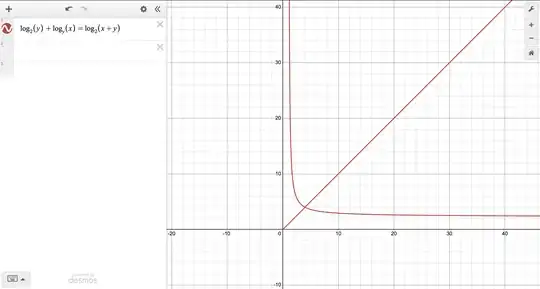

Low effort update: I have graphed the solution for $x$ with respect to $n$ in Desmos, and ignoring the line that corresponds to $x=n$, there is a strange second curve that apparently converges to some value around $2$ as $x\to \infty$:

High-effort update: I was looking for a parametric representation, so I took $$2^{\log_x(n)}x=x+n$$ and substituted in $n=x^k$. After all there has to be some $k$ such that $\log_{x_{sol}}(n)=k$. I've noticed that $n>x_{sol}$ if $n>4$ and $n<x_{sol}$ if $n<4$, which means $k<0$ if $n>4$ and vice versa otherwise. We get $$2^kx=x+x^k \Rightarrow 2^k-1=x^{k-1} \Rightarrow x=(2^k-1)^{\frac{1}{k-1}}$$ which I thought was cool but then I remembered I need $x$ as a function of $n$ exclusively, and $k$ is in terms of both $x$ and $n$. Still, this probably means something.

Edit: thanks to @ThinhDinh, who executed a very similar substitution but managed to get an actual parametrization in the form $$\left(\left(2^{\frac{1}{t}}-1\right)^{\frac{1}{1-t}},\left(2^{\frac{1}{t}}-1\right)^{\frac{t}{1-t}}\right)$$

Another attempt! What if we raise $2x$ to both sides? $$xx^{\log_2(x)}+2^{\log_x(n)}n=x^{\log_2(x+n)}(x+n)$$ We can rewrite this as $$x^{\log_2(x)+1}+n^{\log_x(2)+1}=(x+n)^{\log_2(x)+1}$$ and rewrite it again by substituting $y=\log_2(x)$: $$\left(2^y\right)^{y+1}+n^{\frac{y+1}{y}}=(2^y+n)^{y+1} \Rightarrow (2^y+n)^{y+1}-(2^y)^{y+1}=n^{\frac{y+1}{y}}$$ I thought this would be easy money suddenly, since that's a difference of powers on the left-hand side, but then I remembered 99% of the time $y \notin \mathbb{Z}$ or even $\mathbb{Q}$. I looked for factorizations of differences of powers for non-integer powers, but all that turned up was this question, which had one comment that doesn't help much and 0 answers. Someone should probably answer it.

I know the question is tagged algebra-precalculus, but a solution that uses any technique, as long as it provides a closed-form solution (or surprisingly concludes that one isn't possible) is fine in my book.