This is an unfinished draft. Perhaps it contains some ideas that someone else can use towards a complete proof. So far this draft shows that any solution must satisfy $e<x\leq9$.

Let $x$ be a positive real number such that

$$\log_2(x)+\log_x(9)=\log_2(x+9).\tag{1}$$

For $\log_x(9)$ to make sense we must have $x\neq1$. We can convert to natural logarithms by noting that

$$\frac{\ln(9)}{\ln(x)}=\log_x(9)=\log_2(x+9)-\log_2(x)=\frac{\ln(x+9)-\ln(x)}{\ln(2)},$$

and hence we have

$$\ln(x)\Big(\ln(x+9)-\ln(x)\Big)=\ln(2)\ln(9).\tag{2}$$

To find all solution without using derivatives, it matters to know your definition of the natural logarithm for positive reals. I'll take it to be the unique inverse of the exponential function $x\ \mapsto\ e^x$. I'll use the following two facts about the exponential function, proofs can be found elsewhere on this forum:

Observation 1: The function $f(t):=\left(1+\frac1t\right)^t$ is strictly increasing with $\lim_{t\to\infty}f(t)=e$.

Proof. See for example here.$\qquad\square$

Observation 2: The function $g(t):=\left(1+\frac1t\right)^{t+1}$ is strictly decreasing with $\lim_{g\to\infty}f(t)=e$.

Proof. See for example here.$\qquad\square$

Lemma 3: For all $t>0$ we have

$$\ln(t+1)-\ln(t)<\frac1t.$$

Proof. By elementary algebraic manipulation this is equivalent to

$$\ln\left(1+\frac1t\right)<\frac1t

\qquad\text{ and hence to }\qquad

e>\left(1+\frac1t\right)^t,

$$

which holds for all $t>0$ by Observation 1. $\qquad\square$

Substituting $t=\tfrac x9$ into equation $(2)$ we get

$$\ln(2)\ln(9)=\ln(9t)\Big(\ln(t+1)-\ln(t)\Big),$$

and hence applying Lemma 3 yields

$$\ln(2)\ln(9)<\frac{\ln(9t)}{t}, \qquad\text{ or equivalently}\qquad \frac{\ln(x)}{x}>\frac{\ln(2)\ln(9)}{9}.$$

Lemma 4: The function $\frac{\ln(x)}{x}$ is strictly increasing for $x<e$, and strictly decreasing for $x>e$.

Proof. Let $x>y>e$. Then we want to show that $\frac{\ln(x)}{x}<\frac{\ln(y)}{y}$, or equivalently $x^y<y^x$. Writing $x:=(1+c)y$ with $c>0$, it suffices to shows that

$$\left((1+c)y\right)^y<y^{(1+c)y},\qquad\text{ or equivalently }\qquad y>(1+c)^{\tfrac1c}.$$

With Observation 1 this follows immediately from the fact that $y>e$. The proof for $y<x<e$ is entirely analogous.$\qquad\square$

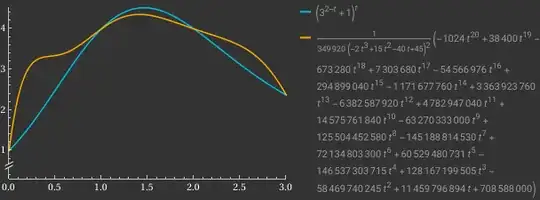

This shows that the left hand side of equation $(2)$ is monotonically increasing for $x<e$, because

$$2^{\ln(9)}=\left(1+\frac9x\right)^{\ln(x)}=\left(\left(1+\frac9x\right)^{\frac{x}{9}}\right)^{9\frac{\ln(x)}{x}}.$$

The base $\left(1+\frac9x\right)^{\frac{x}{9}}$ is strictly increasing by Observation 1, and the exponent is strictly increasing for $x<e$ by Lemma 4. So for $x\leq e$ we have

$$\left(1+\frac9x\right)^{\ln(x)}\leq \left(1+\frac9e\right)^{\ln(e)}=1+\frac9e.$$

It is a matter of elementary algebra to show that $2^{\ln(9)}>1+\tfrac9e$, and so we conclude that any solution to equation $(1)$ must have $x>e$.

Similarly we can obtain a better upper bound by using Observation 2 and a slight variation on Lemma 4:

Lemma 5: The function $\frac{\ln(x)}{x+9}$ is strictly decreasing for $x>9$.

Proof. Let $x>y>9$. Then we want to show that $\frac{\ln(x)}{x+9}<\frac{\ln(y)}{y+9}$, or equivalently $x^{y+9}<y^{x+9}$. Writing $x:=(1+c)y$ with $c>0$, it suffices to shows that

$$\left((1+c)y\right)^{y+9}<y^{(1+c)y+9},\qquad\text{ or equivalently }\qquad y^{\tfrac{y}{y+9}}>(1+c)^{\tfrac1c}.$$

By Observation 1 we have $(1+c)^{\tfrac1c}<e$ and it is clear that $y^{\tfrac{y}{y+9}}$ is strictly increasing for $y>1$. For $y=9$ we have $y^{\tfrac{y}{y+9}}=3>e$, which completes the proof.$\qquad\square$

Now as before we can decompose the left hand side of $(2)$ as follows:

$$2^{\ln(9)}=\left(1+\frac9x\right)^{\ln(x)}=\left(\left(1+\frac9x\right)^{\frac{x+9}{9}}\right)^{9\frac{\ln(x)}{x+9}}.$$

As before, the base $\left(1+\frac9x\right)^{\frac{x+9}{9}}$ is strictly decreasing by Observation 2, and the exponent is strictly decreasing for $x>9$ by Lemma 5. For $x=9$ we of course find that $\left(1+\frac9x\right)^{\ln(x)}=2^{\ln(9)}$, so this shows that there are no solutions with $x>9$.

Some remarks

- The proof of Lemma 5 shows that we can improve this upper bound for

$x$ a bit; we readily see that $y^{\tfrac{y}{y+9}}>e$ for $y=9$, but

it is also clear that this is true for some smaller values of $y$.

With the help of a computer this goes down to $y\approx8.2$ and so

the only solution with $x>8.2$ is $x=9$.

- The proof of Observation 2 can be sharpened to show that $h(t)=(1+\tfrac1t)^{t+\tfrac12}$ is strictly decreasing, again with limit $e$ of course. Then we can use the same argument as in the proofs of Lemma's 4 and 5 for the function $\frac{\ln(x)}{x+9/2}$, to show that it is strictly decreasing for $x>6$ (or even $x>5.86$ with the help of a computer), and hence conclude that $x=9$ is the unique solution with $x>6$.

$g(t)$ and

$g(t)$ and

First $x = 9$ is a natural solution. Note $9$ is a perfect square so this is also equal to $\ln(3) \ln(4)$. This yields the other natural solution $x = 3$. Not sure about the increasing and decreasing though.

– Pavan C. Jun 21 '25 at 03:18