I am reading Evans PDE book and I am working up to the Sobolev Embedding Theorem. While reading through the proof of the fact that all $u\in W^{1,p}(U)$ that satisfy $Tu=0$ are also in $W^{1,p}_0(U)$. However, the setup feels a bit loose. From page 274,

Using partitions of unity and flattening out $\partial U$ as usual, we may as well assume $$\begin{cases}u\in W^{1,p}(\Bbb R^n_+),& u~\text{has compact support in}~\bar{\Bbb R}^n_+, \\ Tu=0~\text{on}~\partial\Bbb R^n_+\end{cases}$$

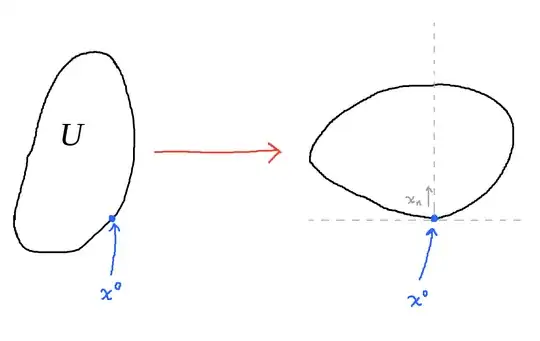

Basically what Evans is doing here is choosing some point $x^0\in\partial U$ and making a change of coordinate such that $x_0$ is the new origin and the $x_n$ axis is exactly aligned with the negative of the outward normal vector to $\partial U$ at $x^0$, like below:

I don't see how we can guarantee that $u=0$ in $\Bbb R^n\setminus \bar{\Bbb R}^n_+$. In the statement of the extension theorem, we could only guarantee that $ \operatorname{supp}(Eu)=V$ for some $V\supset\supset U$. In other words, when extending functions $u\in W^{1,p}(U)$ to $W^{1,p}(\Bbb R^n)$, we in general need to have a little bit of "wiggle room" to damp down the values of $u$ and $D^\alpha u$ before we can safely set it to zero everywhere else, in order to maintain integrability of $D^\alpha u$. This to me makes sense.

However, Evans appears to be asserting, without proof, that in the special case where $Tu=0$, that no wiggle room is required. With the statement of the Extension theorem below:

THEOREM (Extension Theorem). Assume $U\subset \Bbb R^n$ is open and bounded, with $C^1$ boundary. Choose any open set $V\subseteq \Bbb R^n$ such that $U\subset \subset V$. Then, there exists a bounded linear operator $$E:W^{1,p}(U)\to W^{1,p}(\Bbb R^n)$$ such that for all $u\in W^{1,p}(U)$,

(i) $Eu=u$ almost everywhere in $U$,

(ii) $\operatorname{supp}(Eu)\subseteq V$ and

$$\Vert Eu\Vert_{W^{1,p}(\Bbb R^n)}\leq C \Vert u\Vert_{W^{1,p}(U)}$$ For some $C\geq 0$ depending only on $p$, $U$, and $V$.

Evans appears to be asserting the additional statement:

$$\text{Additionally, if}~~Tu=0, ~\text{then}~\operatorname{supp}(Eu)\subseteq U.\tag{☆}$$

My questions: Is $(☆)$ true? In other words, for functions $u\in\ker T$, is the trivial extension $$E u=\begin{cases}u & \text{in}~U \\ 0 & \text{in}~\Bbb R^n\setminus U\end{cases}$$ Also a valid extension, in the sense that $Eu\in W^{1,p}(\Bbb R^n)$ and that it obeys (ii) ? Essentially this boils down to showing that for zero-trace functions, there cannot be any bad discontinuities on $\partial U$. To me this seems intuitively obvious, but I can't quite pin down the details.

I would be happy if someone could provide a proof of this even by first taking for granted that $\ker T=W^{1,p}_0$, even though this is the thing I am trying to prove in the first place. This is purely a matter of intellectual curiosity at this point.

More directly, is there any way that I can understand Evans's construction, without needing an improvement of the Extension theorem first? In particular, how can I see that the aforementioned "wiggle room" is not needed?