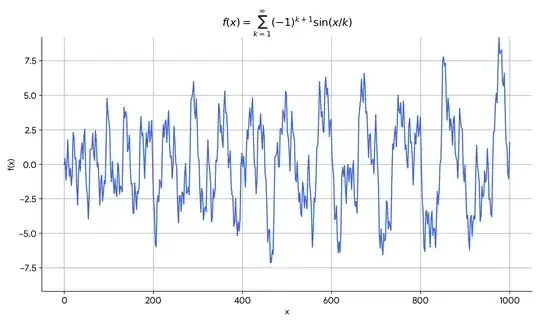

Looking at the zero of $f$, I had to prove a stronger quantitative result about its growth rate. Specifically, that the weighted integral $\int_1^\infty |f(x)|/x \, dx$ diverges. In order to do so, I proved a result that also confirmed @Conrad intuition that $f(x) = O(x^\epsilon)$ is only possible for $\epsilon \ge 1/4$.

Result: There exists a positive constant $c$ such that for all sufficiently large $T$, the function $f(x)$ satisfies the inequality:

$$ \int_0^T f(x)^2 dx \ge \frac{c T^{3/2}}{\sqrt{\ln T}} $$

The Proof Strategy

The proof quantifies the argument from contradiction. Instead of taking limits as $T \to \infty$, we analyze the behavior for finite $T$ and a carefully chosen (large) integer $N$.

Let $\psi_k(x) = \sin(x/k)$ and define the partial sum $S_N(x) = \sum_{k=1}^N (-1)^{k+1} \psi_k(x)$. We use the time-averaging inner product $\langle g, h \rangle_T = \frac{1}{T}\int_0^T g(x)h(x) dx$.

Since the integral of a non-negative function is non-negative, we have:

$$ \langle f - S_N, f - S_N \rangle_T \ge 0 $$

Re-arranging the terms we can get this lower bound for the mean-square of $f$:

$$ \frac{1}{T}\int_0^T f(x)^2 dx \ge \langle S_N, S_N \rangle_T + 2\langle f-S_N, S_N \rangle_T $$

The core of the proof is to find a sharp lower bound for the right-hand side.

Bounding Tools

Paired Term Bound: Let $g(y) = \frac{1}{2}[\text{sinc}(T(y-1/k)) - \text{sinc}(T(y+1/k))]$, so that $\langle \psi_j, \psi_k \rangle_T = g(1/j)$. For $2m-1 \ge 2k$, we apply the Mean Value Theorem to $g(y)$ on the interval $[1/(2m), 1/(2m-1)]$:

$$ |\langle \psi_{2m-1}, \psi_k \rangle_T - \langle \psi_{2m}, \psi_k \rangle_T| = |g(\frac{1}{2m-1}) - g(\frac{1}{2m})| = |g'(c)| \cdot \frac{1}{(2m-1)(2m)} $$

for some $c \in (\frac{1}{2m}, \frac{1}{2m-1})$. The derivative is $g'(y) = \frac{T}{2}[\text{sinc}'(T(y-1/k)) - \text{sinc}'(T(y+1/k))]$. Using $|\text{sinc}'(x)| \le 2/|x|$ for large $|x|$ and noting that for $y \in [1/(2m), 1/(2m-1)]$ and $2m-1 \ge 2k$, we have $|T(y-1/k)| \ge T/(2k)$ and $|T(y+1/k)| \ge T/k$. Thus, $|g'(c)| \le \frac{T}{2}(\frac{2}{T/(2k)} + \frac{2}{T/k}) = \frac{T}{2}(\frac{4k}{T}+\frac{2k}{T}) = 3k$. This gives the final bound:

$$ |\langle \psi_{2m-1}, \psi_k \rangle_T - \langle \psi_{2m}, \psi_k \rangle_T| \le \frac{3k}{(2m-1)(2m)} $$

Dot product bound: For $j \ne k$, the integral is $T\langle \psi_j, \psi_k \rangle_T = \frac{1}{2}\left(\text{sinc}(T(\frac{1}{j}-\frac{1}{k})) - \text{sinc}(T(\frac{1}{j}+\frac{1}{k}))\right)$. Using the triangle inequality and $|\text{sinc}(x)| \le 1/|x|$ for $x \ne 0$:

$$ T|\langle \psi_j, \psi_k \rangle_T| \le \frac{1}{2}\left(|\text{sinc}(T\frac{k-j}{jk})| + |\text{sinc}(T\frac{k+j}{jk})|\right) \le \frac{1}{2}\left(\frac{jk}{|k-j|} + \frac{jk}{k+j}\right) \le \frac{jk}{|k-j|} $$

Harmonic Sum Bound: This is a summed version of the Dot product bound. Because of symmetry we have $\sum_{k,j=1, k\ne j}^L \frac{kj}{|k-j|}= 2 \sum_{k=2}^L k \sum_{j=1}^{k-1} \frac{j}{k-j}$. Re-indexing the inner sum with $l=k-j$ gives $\sum_{l=1}^{k-1} \frac{k-l}{l} = kH_{k-1} - (k-1)$. The total sum is $2 \sum_{k=2}^L (k^2 H_{k-1} - k(k-1))$. Using the standard inequality $H_{n} < \ln(n) + 1$ and bounding the sums, one can establish an explicit upper bound. For $L \ge 2$, a safe and practical bound is given by:

$$ T\sum_{k,j=1, k\ne j}^L |\langle \psi_j, \psi_k \rangle_T| \le \sum_{k,j=1, k\ne j}^L \frac{kj}{|k-j|} \le \frac{2L^3 \ln L}{3} + L^3 $$

The Main Calculation

To connect our strategy to the errors, we first expand the term $\langle S_N, S_N \rangle_T$:

$$ \langle S_N, S_N \rangle_T = \sum_{j,k=1}^N (-1)^{j+k} \langle \psi_j, \psi_k \rangle_T = \sum_{k=1}^N \langle \psi_k, \psi_k \rangle_T + \sum_{j \ne k, j,k \le N} (-1)^{j+k} \langle \psi_j, \psi_k \rangle_T $$

The diagonal terms are $\langle \psi_k, \psi_k \rangle_T = \frac{1}{2} - \frac{k}{4T}\sin(\frac{2T}{k})$. Summing these from $k=1$ to $N$ gives $\frac{N}{2} + \sum_{k=1}^N \frac{k}{4T}\sin(\frac{2T}{k})$. The inequality $\frac{1}{T}\int_0^T f(x)^2 dx \ge \langle S_N, S_N \rangle_T + 2\langle f-S_N, S_N \rangle_T$ becomes:

$\frac{1}{T}\int_0^T f(x)^2 dx \ge \frac{N}{2} + E_1(N,T) + E_2(N,T) + E_3(N,T)$ where:

- $E_1(N,T) = \sum_{k=1}^N \frac{k}{4T}\sin(\frac{2T}{k})$

- $E_2(N,T) = \sum_{j \ne k, j,k \le N} (-1)^{j+k} \langle \psi_j, \psi_k \rangle_T$

- $E_3(N,T) = 2\langle f-S_N, S_N \rangle_T = 2\sum_{k=1}^N (-1)^{k+1} \sum_{j=N+1}^\infty (-1)^{j+1} \langle \psi_j, \psi_k \rangle_T$

Our inequality becomes:

$$\int_0^T f(x)^2 dx \ge \frac{NT}{2} - T|E_1(N,T)| - T|E_2(N,T)| - T|E_3(N,T)| $$

Bounding the Errors:

$T|E_1(N,T)| \le \sum_{k=1}^N \frac{k}{4} = \frac{N(N+1)}{8}$. This is negligible.

$T|E_2(N,T)| \le T\sum_{j \ne k, j,k \le N} |\langle \psi_j, \psi_k \rangle_T|$. Using Bounding Tool 3 (the Harmonic Sum Bound), this is bounded by $\frac{2N^3\ln N}{3} + N^3$.

$T|E_3(N,T)|$: We use a hybrid approach. We introduce a global integer cutoff $J > N$, which will be chosen optimally later (it will be of order $\sqrt{T}$ while $N$ of order $\sqrt{T/\ln T}$). The sum over $j$ is split into a "head" ($N<j<J$) and a "tail" ($j \ge J$).

$$ T|E_3(N,T)| \le 2T \sum_{k=1}^N \sum_{j=N+1}^{J-1} |\langle \psi_j, \psi_k \rangle_T| + 2T \left| \sum_{k=1}^N (-1)^{k+1} \sum_{j=J}^{\infty} (-1)^{j+1} \langle \psi_j, \psi_k \rangle_T \right| $$

Tail Part: We choose $J \ge 2N+2$ so that Bounding Tool 1 (the Paired Term Bound) applies for all $k \le N$. Pairing terms in the sum over $j$ yields a bound independent of $T$:

$$ T|\text{Tail}| \le 2T \sum_{k=1}^N \sum_{m=\lceil J/2 \rceil}^\infty \frac{3k}{(2m-1)(2m)} \le 6T \left(\sum_{k=1}^N k\right) \left(\sum_{m=\lceil J/2 \rceil}^\infty \frac{1}{m(m-1)}\right) $$

The inner sum is a telescoping series equal to $\frac{1}{\lceil J/2 \rceil-1} \le \frac{2}{J-2}\le \frac{3}{J}$ for $J$ large enough.

$$ T|\text{Tail}| \le 6T \frac{N(N+1)}{2} \frac{2}{J-2} \le 9T \frac{N(N+1)}{J}$$

Head Part: For terms where $N<j<J$, we use Bounding Tool 2 (Dot product bound) and sum over the precise region.

$$ T|\text{Head}| \le 2 \sum_{k=1}^N \sum_{j=N+1}^{J-1} \frac{jk}{|j-k|} = 2 \sum_{k=1}^N k \sum_{j=N+1}^{J-1} \frac{j}{j-k} $$

We analyze the inner sum: $\sum_{j=N+1}^{J-1} \frac{j}{j-k} = \sum_{j=N+1}^{J-1} (1 + \frac{k}{j-k}) = (J-N-1) + k \sum_{l=N+1-k}^{J-1-k} \frac{1}{l}$. This is bounded by $(J-N) + k \ln(\frac{J-k}{N-k+1}) \le J + k \ln(J)$. Summing over $k$ gives:

$$T|\text{Head}| \le 2\sum_{k=1}^N (kJ + k^2\ln J) = J N(N+1) + \frac{N(N+1)(2N+1)}{3}\ln J$$

Now we combine the errors for $E_3$. The total error from this term is bounded by:

$$ T|E_3(N,T)| \le J N(N+1) + \frac{9T N(N+1)}{J} + \frac{N(N+1)(2N+1)}{3}\ln J $$

To minimize the sum of the first two terms, which depend on our choice of $J$, we balance them by setting $J N(N+1) \approx 9T N(N+1)/J$. This implies $J^2 \approx 9T$, so we make the optimal choice $J = \lfloor 3\sqrt{T} \rfloor$. With this choice, for large $T$:

$$ J N(N+1) \le 3\sqrt{T} N(N+1) \quad \text{and} \quad \frac{9T N(N+1)}{J} \le 4\sqrt{T} N(N+1) $$

Their sum is $7\sqrt{T}N(N+1)$. The logarithm term becomes $\ln J \le \ln(3\sqrt{T}) \le \ln T$ for large $T$. Substituting these into the bound for $T|E_3(N,T)|$ gives:

$$ T|E_3(N,T)| \le 7\sqrt{T}N(N+1) + \frac{N(N+1)(2N+1)}{3}\ln T $$

Optimization and Conclusion

We have established the inequality:

$$ \int_0^T f(x)^2 dx \ge \frac{NT}{2} - \sum_i T|E_i| $$

We wish to show that for an appropriate choice of $N$, this error is smaller than the main term $\frac{NT}{2}$. Let us choose $N = \left\lfloor\sqrt{\frac{T}{8\ln T}}\right\rfloor$. For sufficiently large $T$, this implies $N \ge 1$ and $N > \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\sqrt{\frac{T}{8\ln T}}$.

Upper Bound for the Error Term:

Using the bounds from the previous sections, the total error is bounded by:

$$ \sum_i T|E_i| \le \frac{N(N+1)}{8} + \left(\frac{2N^3\ln N}{3} + N^3\right) + \left(7\sqrt{T}N(N+1) + \frac{N(N+1)(2N+1)}{3}\ln T\right) $$

We use the inequalities $N \le \sqrt{\frac{T}{8\ln T}}$ and $\ln N \le \frac{1}{2}\ln T$ (for large $T$). Let's bound the sum of errors, adding some $>1$ factors to simplify expressions for large $N, T$ :

$$ \sum_i T|E_i| \le \frac{N^2}{4} + N^3 + 14\sqrt{T}N^2 + \frac{4}{3} N^3\ln T $$

The dominant term is the last one. Let's bound it:

$$\frac{4}{3} N^3\ln T \le \left(\frac{T}{8\ln T}\right)^{3/2}\ln T = \frac{1}{12\sqrt{2}} \frac{T^{3/2}}{\sqrt{\ln T}} $$

The other terms are of a lower order. For instance, $14\sqrt{T}N^2 \le 14\sqrt{T}\frac{T}{8\ln T} = \frac{7}{4}\frac{T^{3/2}}{\ln T}$. For large $T$, the sum of these sub-dominant terms is much smaller than the dominant error term. A generous but safe bound for the total error for large $T$ is $\sqrt{2}$ the dominant part:

$$ \sum_i T|E_i| \le \sqrt{2} \cdot \frac{1}{12\sqrt{2}} \frac{T^{3/2}}{\sqrt{\ln T}} = \frac{1}{12} \frac{T^{3/2}}{\sqrt{\ln T}} $$

Lower Bound for the Main Term:

$$ \frac{NT}{2} > \frac{1}{2}\left(\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\sqrt{\frac{T}{8\ln T}}\right)T = \frac{T^{3/2}}{8\sqrt{\ln T}} $$

Final Inequality:

Combining the lower bound for the main term and the upper bound for the error gives:

$$ \int_0^T f(x)^2 dx \ge \frac{T^{3/2}}{8\sqrt{\ln T}} - \frac{1}{12} \frac{T^{3/2}}{\sqrt{\ln T}}=\frac{1}{24}\frac{T^{3/2}}{\sqrt{\ln T}} $$

Since $c = \frac{1}{24} > 0$, we have proven that for all sufficiently large $T$, the integral is bounded below as required. This completes the proof.

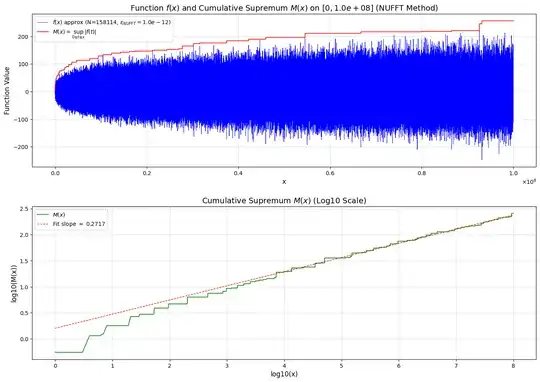

Implications for possible $\epsilon$ such that $f(x)=O(x^\epsilon)$ and $\sup_{|y| \le x} |f(y)|$

This result provides important lower bound on the growth exponent. Indeed, y the proven inequality:

$c \sqrt{\frac{T}{\ln T}} \le \frac{1}{T} \int_0^T f(x)^2 dx \le \left(\sup_{|t| \le T} |f(t)|\right)^2$. Implying directly that:

$$\sup_{|t| \le x} |f(t)| = \Omega(x^{1/4}/\ln(x)^{1/4})$$

This proves that the growth exponent of $f(x)$ cannot be less than $1/4$. Combining this with the elementary upper bound $f(x) = O(\sqrt{x})$ (from pairing terms), we can conclude that $f(x) = O(x^\epsilon)$, the optimal exponent lying in the range $[1/4, 1/2]$.

Divergence of the Weighted Integral $\int |f(x)|/x \, dx$

The main result on the mean-square lower bound provides the necessary tool to prove the divergence of $\int_1^\infty |f(x)|/x \, dx$. The proof is a consequence of the conflict between the mean-square lower bound and the elementary growth upper bound $f(x)=O(\sqrt{x})$. We proceed by contradiction.

Assume the integral $\int_1^\infty \frac{|f(x)|}{x} dx$ converges.

From the elementary bound $f(x) = O(\sqrt{x})$, there exists a constant $K$ such that $|f(x)| \le K\sqrt{x}$ for $x \ge 1$. This implies the inequality $\frac{f(x)^2}{x^{3/2}} \le K \frac{|f(x)|}{x}$. By the comparaison, the convergence assumed in step 1 implies that the integral $\int_1^\infty \frac{f(x)^2}{x^{3/2}} dx$ must also converge.

We now show this conclusion is incompatible with the mean-square lower bound. We use integration by parts on the integral $\int_1^T \frac{f(x)^2}{x^{3/2}} dx$, relating it to the energy integral $S(T) = \int_0^T f(x)^2 dx$. Using the lower bound $S(t) \ge \frac{c t^{3/2}}{\sqrt{\ln t}}$ for $t \ge t_0$, the integration by parts formula $\int_1^T \frac{S'(t)}{t^{3/2}} dt = \left[\frac{S(t)}{t^{3/2}}\right]_1^T + \frac{3}{2}\int_1^T \frac{S(t)}{t^{5/2}} dt$ yields a lower bound for $\int_1^T \frac{f(x)^2}{x^{3/2}} dx$ that involves the integral $\int_{t_0}^T \frac{1}{t\sqrt{\ln t}} dt$. This integral is known to diverge (its antiderivative is $2\sqrt{\ln t}$). Since all terms in the integration by parts formula are non-negative for large $t$, the divergence of this term implies that $\int_1^\infty \frac{f(x)^2}{x^{3/2}} dx$ must diverge. However, from step 2, we concluded this integral must converge. This is a contradiction. Thus, the assumption is false and $\int_1^\infty \frac{|f(x)|}{x} dx$ diverges.

The framework of this proof can be generalized. Assuming we have a better upper bound $f(x) = O(x^\alpha)$ for some $\alpha < 1/2$, the mean-square lower bound allows us to establish two stronger quantitative results. First that $\int_0^T |f(x)|dx = \Omega(T^{3/2-\alpha}/\sqrt{\ln T})$ and second, the weighted integral $\int_1^\infty \frac{|f(x)|}{x^{3/2-\alpha}} dx$ must diverge.

Note that @Conrad in his answer to an other question regarding the zeros of f has also proved $\int |f(x)|/x \, dx$ diverges with a simpler argument based "only" on the weaker result proved in his answer to this current question: $\frac{1}{T}\int_0^Tf(x)\sin (x/k) dx \to (-1)^{k+1}/2$ impliying $1/4 \le \frac{1}{T}\int_T^{2T}f(x)\sin x dx \le \frac{2}{2T}\int_T^{2T} |f(x)| dx \le 2\int_T^{2T} \frac{|f(x)|}{x} dx$ and the divergence.