This question came up when I was graphing the function

$$f(x)=\sum_{n=1}^\infty\frac{(-1)^n}{n^2}H(\{x\} - \{\varphi n\}),$$

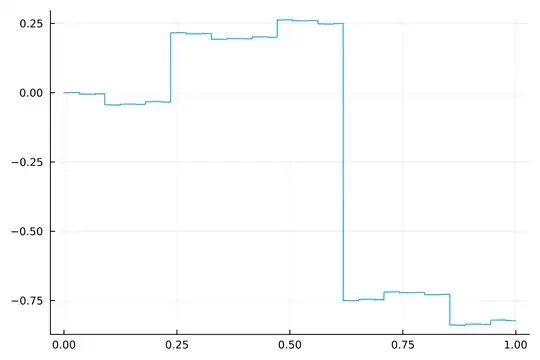

where $\{x\}$ is the fractional part of $x$, $\varphi=(\sqrt5+1)/2\approx 1.618$ is the golden ratio, and $H$ is the Heaviside step function. (We could also use $(\sqrt5-1)/2$; modulo $1$, it's the same.) The graph looks like this:

I was just trying to draw a nice-looking visual for another question. But something interesting jumps out in the graph!

The question

It looks a lot like $f(\varphi^-)=\frac14$ and $f(\varphi^+)=-\frac34$. However, more careful numerical work shows that we don't have an exact equality. Instead, $f(\varphi^-)\approx\frac14-1.94\times10^{-5}$. So the question is, why is it so close?

Moreover, why does $f(3\varphi^-) \approx -\frac{8}{11}$ and $f(4\varphi^-) \approx \frac15$ with similarly small errors?

What I'd like

The dream would be some closed form like $f(k\varphi^-)=\frac{p(k)}{q(k)}+g(k)$ for nice functions $p,q:\mathbb N\to\mathbb N$ and $g:\mathbb N\to\mathbb R$, where we can see that $q(k)$ and $g(k)$ are small for $k=1,3,4$, for some satisfying big-picture reason.

Other potential forms of partial explanation might be:

- A formula to accelerate the defining series of $f$, with truncation errors that are $o(n^{-1})$, especially if this series can be truncated to recover our $k=1,3,4$ results.

- A not-so-nice function $g(k)$ that nonetheless admits satisfying bounds.

- An argument that $f$ must take such approximately-simple values for several small $k$, even if we don't have a constructive argument to find those $k$. But in this case, I would really want the argument to be quantitative enough that it's no longer surprising to see three small $q=4,11,5$ with tiny errors like $10^{-5}$, and/or partial fraction convergents with such large denominators.

- An exact transform or functional equation relating $f$ to some other function where the above explanations are possible.

I have no strategy to accomplish any of this. I have a vague intuition that as $n$ becomes large, comparably large ranges of even and odd terms of $f(x)$ become closer to uniform distributions, so it's no surprise that they would start to cancel out in some sense. But even if that intuition is formalized, it's hard to see how it could yield such close approximations.

In any case, I'll add some more advanced tags to this question, in case those methods have some application.

Appendix

Here's my latest numerical evidence, reproducing findings by anankElpis and Michael Lugo in the comments. Using JuliaIntervals for interval arithmetic and adding terms up to $n=10^8$, we have:

$$f(\varphi^-) \in [0.249980594, 0.249980615] = \frac14 - 1.9396\times10^{-5} \pm 10^{-8}$$ $$f(3\varphi^-) \in [-0.727287914, -0.727287893] = -\frac{8}{11} - 1.5177\times10^{-5} \pm 10^{-8}$$ $$f(4\varphi^-) \in [0.1999785740, 0.1999785941] = \frac15 - 2.1416\times10^{-5} \pm 10^{-8}$$

Note that the worst-case error of $10^{-8}$ from truncating the series dominates the much smaller errors from floating-point rounding, or from the occasional $n$ term where I can't confidently evaluate $H()$.

In terms of continued fractions, abusing notation to allow for my computation's uncertainty in the last convergent:

$$f(\varphi^-) = \cfrac{1}{4+\cfrac{1}{[3220, 3223] + \cdots}}$$ $$f(3\varphi^-) = \cfrac{1}{1+\cfrac{1}{2+\cfrac{1}{1+\cfrac{1}{2+\cfrac{1}{[543, 544]+\cdots}}}}}$$ $$f(4\varphi^-) = \cfrac{1}{5+\cfrac{1}{[1866, 1868] + \cdots}}$$