I am trying to find an example of a topological space admitting two non-isomorphic covering spaces $(S,p)$ and $(T,q)$ for which there exists a homomorphism $\phi$ of $(S,p)$ into $(T,q)$ and a homomorphism $\psi$ of $(T,q)$ into $(S,p)$ (see Note 1 below for the notation and terminology used here and for the implicit assumptions we make).

I am pretty sure such an example exists, but I could not find any up to now, so any help is welcome. Thank you very much in advance for your kind attention.

NOTE 1. All topological spaces in this post are assumed to be path connected and locally path connected, as it is usual in the theory of covering spaces.

For any topological space $X$ and any $x \in X$, the fundamental group of $X$ at the base point $x$ is denoted by $\pi(X,x)$. Given two spaces $X$ and $Y$, a continuous map $f:X \rightarrow Y$ and a point $x \in X$, we denote by $f_{*}:\pi(X,x) \rightarrow \pi(Y,f(x))$ the homomorphism defined by $f_{*}([\gamma])=[f \circ \gamma ]$ for any loop $\gamma$ at $x$.

If $\alpha:[0,1] \rightarrow X$ is a path in $X$, with $\alpha(0)=x_0$ and $\alpha(1)=x_1$, then $\pi_{\alpha}:\pi(X,x0) \rightarrow \pi(X,x_1)$ denotes the isomorphism defined by $\pi_{\alpha}([\gamma])=[(\alpha^{-1} \cdot \gamma) \cdot \alpha]$ for any loop $\gamma$ at $x_0$, where $\alpha^{-1}$ is the inverse path of $\alpha$, that is $\alpha^{-1}(s)=\alpha(1-s)$ for any $s \in [0,1]$, and for any two paths $\sigma$, $\tau$ in $X$ with $\sigma(1)=\tau(0)$, the product $\sigma \cdot \tau$ is defined by \begin{equation} (\sigma \cdot \tau) (s) = \begin{cases} \sigma(2s) & 0 \leq s \leq 1/2, \\ \tau(2s-1) & 1/2 \leq s \leq 1. \end{cases} \end{equation}

A covering space $(S,p)$ of a space $X$ consists of a topological space $S$ and a continuous surjective map $p:S \rightarrow X$ such that for any $x \in X$ there exists an open neighborhood $U$ of $x$ such that $p^{-1}(U)$ is the disjoint union of open sets, each of which is mapped homeomorphically by $p$ onto $U$. Given two covering spaces $(S,p)$ and $(T,q)$ of $X$ a homomorphism of $(S,p)$ into $(T,q)$ is a continuous map $\phi:S \rightarrow T$ such that $p=q \circ \phi$. A homomorphism $\phi$ of $(S,p)$ into $(T,q)$ is called an isomorphism of $(S,p)$ onto $(T,q)$ if $\phi$ is a homeomorphism of $S$ onto $T$. Two covering spaces $(S,p)$ and $(T,q)$ of $X$ are said to be isomorphic is there exists an isomorphism of one onto the other.

NOTE 2. In the example we are looking for $X$ must have a non-abelian fundamental group. Indeed, if $X$ has an abelian fundamental group, and $(S,p)$ and $(T,q)$ are covering spaces of $X$ for which there exists a homomorphism $\phi$ of $(S,p)$ into $(T,q)$ and a homomorphism $\psi$ of $(T,q)$ into $(S,p)$, then $(S,p)$ and $(T,q)$ turn out to be isomorphic, as the following argument shows.

Choose an arbitrary $s_0 \in S$ and put $t_0=\phi(s_0)$, $s_1=\psi(t_0)$, $x_0=p(s_0)$. We have $$p(s_1)=p(\psi(t_0))=q(t_0)=q(\phi(s_0))=p(s_0)=x,$$

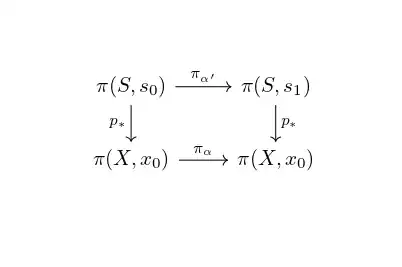

so that $s_0,s_1 \in p^{-1}(x_0)$.We have $$ p_{*}(\pi(S,s_0))=q_{*}(\phi_{*}(\pi(S,s_0))) \subseteq q_{*}(\pi(T,t_0)), $$ and $$ q_{*}(\pi(T,T_0))=p_{*}(\psi_{*}(\pi(T,t_0))) \subseteq p_{*}(\pi(S,s_1)). $$ Let $\alpha':[0,1] \rightarrow S$ be a path such that $\alpha'(0)=s_0$ and $\alpha'(1)=s_1$, and put $\alpha= p \circ \alpha'$. It is easy to verify that the following diagram

commutes, so that the isomorphism $\pi_{\alpha}$ sends the subgroup $p_{*}(\pi(S,s_0))$ of $\pi(X,x_0)$ onto the subgroup $p_{*}(\pi(S,s_1))$. Now since $\pi(X,x_0)$ is abelian and $\alpha$ is a loop at $x_0$ it is easy to check that the isomorphism $\pi_{\alpha}$ is the identity map of $\pi(X,x_0)$, so that $p_{*}(\pi(S,s_0))=p_{*}(\pi(S,s_1))$. By using this fact and the two inclusions proved above we then get $p_{*}(\pi(S,s_0))=q_{*}(\pi(T,t_0))$. This last equality implies in turn the existence of an isomorphism $\theta$ of $(S,p)$ into $(T,q)$ such that $\theta(s_0)=t_0$ (see e.g. Fulton, Algebraic Topology, Corollary 13.6 or Massey, A Basic Course in Algebraic Topology, Chapter 5, Corollary 6.4). Hence $(S,p)$ and $(T,q)$ are isomorphic.