Here is my attempt to blend intuition and formulas, to show explicitly that the identification of a piece of surface of the cone (away from the apex) with a piece of a flat plane, is distance preserving.

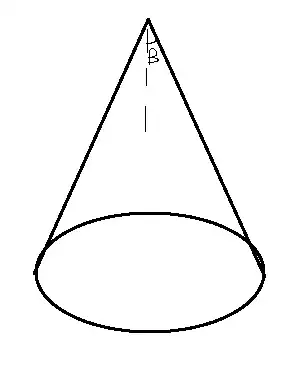

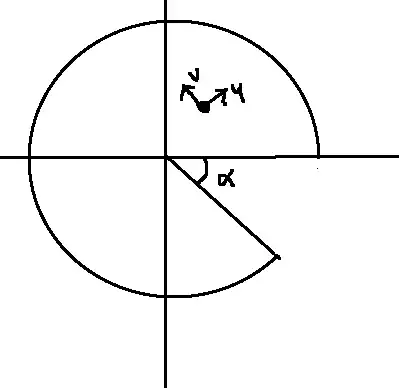

If we remove an $\alpha$ radian sector from a disk, we can it fold into a cone. Going from polar co-ordinates on the remaining disk $$0\leq r\leq 1,\\0\leq \theta\leq 2\pi-\alpha,$$ to cartesian co-ordinates on $\mathbb{R}^3$, this "folding map" may be written:

$$f\colon (r,\theta)\mapsto \left(r \sin\beta\cos\left( \theta \left(\frac{2\pi}{2\pi-\alpha}\right)\right),r \sin\beta\sin\left( \theta \left(\frac{2\pi}{2\pi-\alpha}\right)\right),-r\cos\beta\right).$$

Here $\sin\beta=\frac{2\pi-\alpha}{2\pi}$, and $\beta\in[0,\frac\pi2]$.

Intuitively, all this map does is send (what remains of) concentric circles on the disk to horizontal circles on the cone. As we have removed a sector from the disk, we need to speed up how fast we go round the cone, by a factor of $\frac{2\pi}{2\pi-\alpha}$, so as $\theta$ goes from $0$ to $2\pi-\alpha$, we go all the way round the cone. We incline the slope of the cone $\beta$, so that what remains of the circumference of the disk, equals the entire circumference of the corresponding circle on the cone.

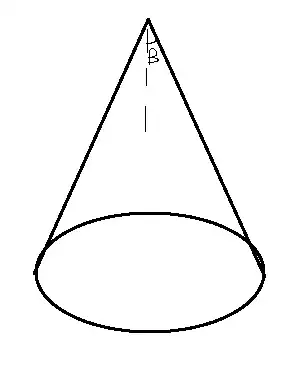

It remains to verify that this map is distance preserving. Given a point $P$ on the disk, let $u$ be the outward facing radial tangent vector at $P$. Let $v$ be the unit anti-clockwise facing tangent vector at $P$. So $$u=\frac\partial {\partial r},\\v=\frac 1r\frac\partial{\partial \theta}.$$

Then $u,v$ form an orthonormal basis of the tangent space at $P$.

$f$" />

$f$" />

We just need to check that $f_*(u),f_*(v)$ form an orthonormal basis of the tangent space at $f(P)$. The reason this is sufficient, is that if a linear map $L\colon U\to V$ takes an orthonormal basis of $U$ to an orthonormal basis of $V$, then an arbitrary pair of vectors in $U$ may be written $\left(\begin{array}{c}a_1\\a_2\\\vdots\end{array}\right),\left(\begin{array}{c}b_1\\b_2\\\vdots\end{array}\right)$ with respect to the first basis, so their images in $V$ will be $\left(\begin{array}{c}a_1\\a_2\\\vdots\end{array}\right),\left(\begin{array}{c}b_1\\b_2\\\vdots\end{array}\right)$ with respect to the second basis. Thus in both cases the dot product of the vectors will be $a_1b_1+a_2b_2+\cdots$, as both basis' are orthonormal. So the map $L$ preserves norms. Once we know $f_*$ preserves norms, then we know $f$ preserves distance, as distances on a surface are obtained by integrating (along paths) norms in tangent spaces.

Intuitively $f_*(u)$ is just the unit vector of steepest descent down the cone. In formulas:

$$f_*(u)=\frac{\partial f}{\partial r}=\left(\sin\beta\cos\left( \theta \left(\frac{2\pi}{2\pi-\alpha}\right)\right), \sin\beta\sin\left( \theta \left(\frac{2\pi}{2\pi-\alpha}\right)\right),-\cos\beta\right)$$

Thus $|f_*(u)|=1$ by the trig identity $\sin^2\phi+\cos^2\phi=1$.

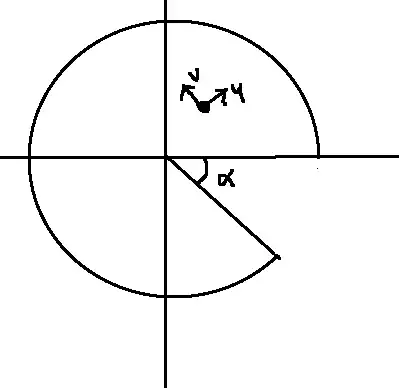

Intuitively $f_*(v)$ is horizontal, hence orthogonal to $f_*(u)$ the vector of steepest descent. Also $|f_*(v)|$ should be $|v|(=1)$ multiplied by $\frac{2\pi}{2\pi-\alpha}$ (as we scale up how fast we go round) multiplied by $\sin \beta=\frac{2\pi-\alpha}{2\pi}$ as the radius of the circle we go round is scaled down. Thus $|f_*(v)|=1$ and $f$ preserves orthonormal basis' of tangent spaces, hence is an isometry.

To confirm our intuition:

$$f_*(v)=\frac1r\frac{\partial f}{\partial \theta}=

\left(-\sin\left( \theta \left(\frac{2\pi}{2\pi-\alpha}\right)\right), \cos\left( \theta \left(\frac{2\pi}{2\pi-\alpha}\right)\right),0\right)$$

This is clearly a unit vector and orthogonal to $f_*(u)$.

$f$" />

$f$" />