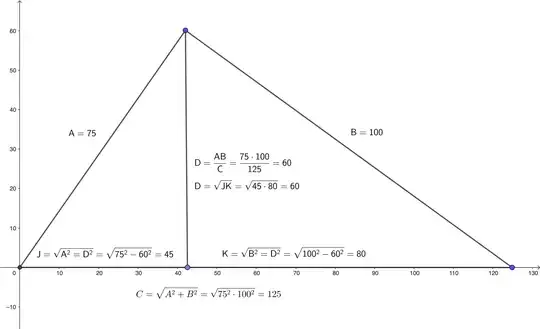

In this question, I was able to show how some Pythagorean triples can be divided into two smaller Pythagorean triples by the perpendicular from the hypotenuse to the right angle... as shown in the example here.

I found a number of these $\,A,B,C,D,J,K\,$ sets generated by this formula and shown in the table below.

\begin{align*} &A=(2n-1+k)^2-k^2&&=(2n-1)^2+2(2n-1)k\\ &B=2(2n-1+k)k &&=\phantom{(2n-1)^2+{}} 2(2n-1)k+2k^2\\ &C=(2n-1+k)^2+k^2 &&=(2n-1)^2+2(2n-1)k+2k^2 \end{align*}

$$\begin{array}{c|c|c|c|c|c|c|c|c|} (n,k) & A & B & C & D & GCD & J & K \\ \hline (3,5) & 75 & 100 & 125 & 60 & 25 & 45 & 80 \\ \hline (7,15) & 175 & 600 & 625 & 168 & 25 & 49 & 576 \\ \hline (7,26) & 845 & 2028 & 2197 & 780 & 169 & 325 & 1872 \\ \hline (8,15) & 675 & 900 & 1125 & 549 & 225 & 405 & 720 \\ \hline (8,45) & 1575 & 5400 & 5625 & 1512 & 225 & 441 & 5185 \\ \hline (13,25) & 1875 & 2500 & 3125 & 1500 & 625 & 1125 & 2000 \\ \hline (13,75) & 4375 & 15000 & 15625 & 4200 & 625 & 1225 & 14400 \\ \hline (15,580) & 34481 & 706440 & 707281 & 34440 & 841 & 1681 & 705600 \\ \hline (18,35) & 3675 & 4900 & 6125 & 2940 & 1225 & 2205 & 3820 \\ \hline (18,105) & 8575 & 29400 & 30625 & 8232 & 1225 & 2401 & 28224 \\ \hline (20,78) & 7605 & 18252 & 19773 & 7020 & 1521 & 2925 & 16848 \\ \hline \end{array}$$

These appear to be very rare. Have I missed any for $\,n\le20,\,$ and is there a more efficient way to find them than a spreadsheet full of formulas that I used?