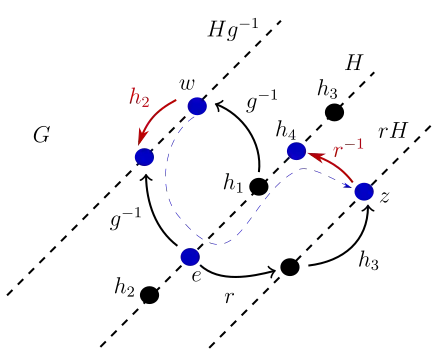

I've read this discussion on Intuition behind normal subgroups, but I'm still unable to create a mental picture of what is going on behind the scenes. I'm trying to build an alternative visualization. For a finite group $G$, a subgroup $H \subset G$ is said normal if satisfies: $$ gH = Hg, \forall g \in G \tag{1} $$ My goal with this question is to come up with a visual interpretation for (1). Let's consider two arbitrary cosets for $G$, $Hg^{-1}, rH$. The cosets are shown below, including their respective representatives $w$ and $z$.

I'm guessing that if we have (the red arrows in the figure): $$ \begin{align} w^{-1} g^{-1} \in H \\ z r^{-1} \in H \end{align} \tag{2} $$ Then, we can build the following path (shown in blue in the figure): $$ gH rH = w^{-1}z = h_{2} g h_{4}r \tag{3} $$ My intuition says that (2) and (3) should be enough to prove (1), but I'm stuck at this moment. This strategy makes any sense at all?

Edit

I ended up reading this beautiful post with some motivation behind normal subgroups. After reading it and with the comments of @JohnDouma, I came up with another view of the problem.

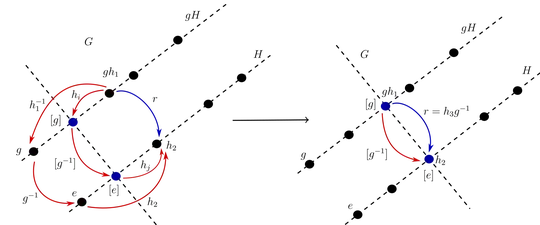

I understood the main idea as follows. Let $gH$ be an arbitrary coset whose representative is $[g]$. For the set of representatives form a group we need: $$ [g] \circ [g^{-1}] = [e] \tag{4} $$ Eq. (4) implies that for any two representatives in $\{ [g], [g^{-1}], [e]\}$ the third is determined.

Note that given $gh_{1} \in gH$, and $h_{2} \in H$, even if $H$ is not normal, we have the following condition (illustrated on the left of the figure below): $$ gh_{1} \circ \underbrace{ (h_{1}^{-1} g^{-1} h _{2}) }_{ r } = h_{2} $$

Now, if $H$ is normal, Eq. (4) implies that for any representative in $[g]$ and $[e]$ we can still create another path which coincides with $r$, which is also shown on the left of the above figure.

In particular, we can think that the simplest description for $r$ will appear when the representative of $[g]$ is $gh_{1}$ and the representative of $[e]$ is $h_{2}$. This implies that $r \in [g^{-1}]$, say $r = h_{3}g^{-1}$, and: $$ \begin{align} g h_{1} \circ h_{3} g^{-1} = h_{2} \implies \\ g h_{4} = h_{2} g \end{align} \tag{5} $$ which implies (1).

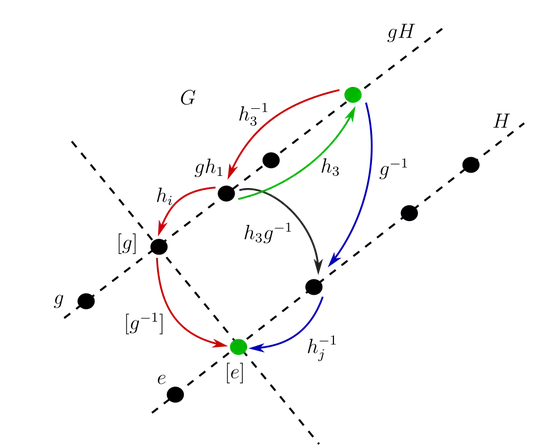

To see more clearly why the elements of $g$ are said to commute with $H$, we can replace $r$ in the left figure by $h_{3}g^{-1}$. The new obtained figure is shown below:

Then, after a translation by $h_{3}$, we find that there are two paths that connect the green points: the red and blue, which implies:

$$ \begin{align} h_{3}^{-1} \circ h_{i} \circ (h_{k}g^{-1}) = g^{-1} \circ h_{j}^{-1} \implies h_{l} g^{-1} = g^{-1}h_{m} \end{align} \tag{6} $$