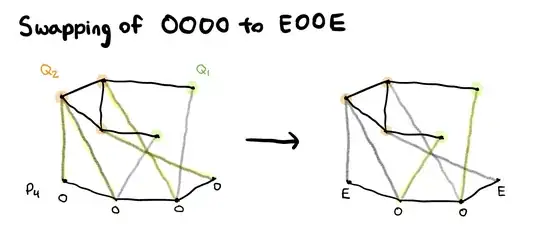

Let $H$ be a graph, all of whose vertices have even degree. We construct a new graph $H'$, isomorphic to the first one, with $V(H)=\{v_1,v_2,...,v_n\}$ and $V(H')=\{v_1',v_2',...v_n'\}$ disjoint. Next, we construct a graph $G_0$, such that $V(G_0)=V(H)\cup V(H')$ and $\{u,v\}\in E(G_0)$ if and only if:

- $\{u,v\}\in E(H),$

- $\{u,v\}\in E(H'),$ or

- $\{u,v\}=\{v_i,v_i'\}$ for some $i$.

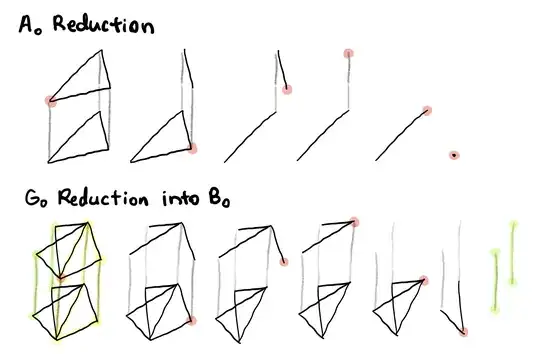

This $G_0$ is our initial graph. In a single operation, we take a vertex of $G_j$ with odd degree and delete it, together with all of its edges, to form a new graph $G_{j+1}$.

For each initial graph, is it possible to find a sequence of moves such that $G_j$ has no edges?

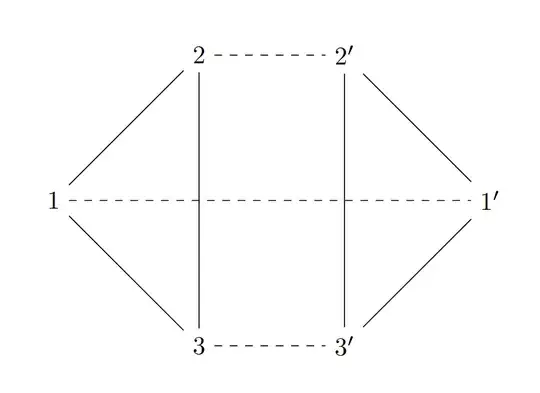

For example, observe the following graph $G_0$, generated by a triangle graph $H$ with $V(H)=\{1, 2, 3\}$:

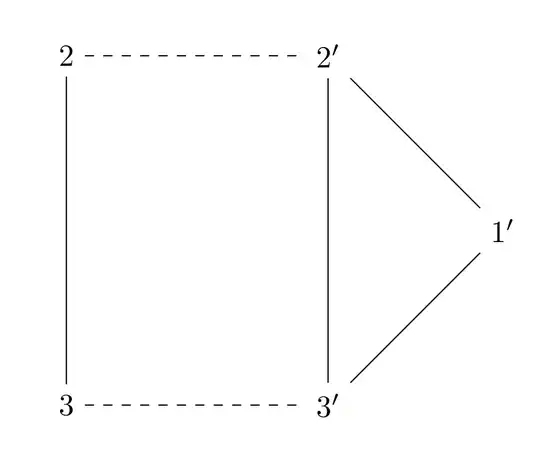

Say we delete vertex $1$, which is allowed as $\deg (1)=3$ is odd. We get graph $G_1$:

Now we delete $2'$ to get the graph $G_2$: $2-3-3'-1'$. We delete $2, 3, 3'$ to get the graphs $G_3, G_4, G_5$ respectively. We are left with $G_5$, which consists only of $1'$.

This problem is a stronger form of IMO Shortlist 2013 C3., where only one application of $(ii)$ is allowed (and this is how I came across this problem).

I tried using induction to prove we can always reduce a graph to one with a lesser chromatic number, but this approach breaks down if one accidentaly deletes a vertex which results in the subsequent graph having all degrees even (for example, a complete graph with $5$ vertices.)

Intuition tells me that this result should hold, as for small graphs $H$, it works for all of them, and for bigger and bigger graphs, we always have a large supply of vertices with an odd degree.

The problem seems much harder that the original problem from the shortlist, so I'm excited to see your observations and insights. Maybe someone finds a counterexample!

Update: An idea that comes to mind is to find a characterization of a reducible graph, that is, a graph (which need not be connected) for which there exists a finite sequence of operations which reduces it to a graph without edges. After we find a characterization, we may inductively assume that a graph with $n-1$ vertices with that characterization is reducible. Then we observe an arbitrary graph with $n$ vertices and try to find a vertex, which after being removed results in a graph which once again satisfies the characterization. The problem arises when we try to explicitly find a characterization (i.e., a condition equivalent to being reducible).

Naively, I came up with the following characterization for irreducible graphs:

A graph is irreducible if and only if when partitioned into connected components $G_1, G_2, ..., G_k$, some subgraph $G_i$ contains at least one edge, and either:

- $G_i$ has only vertices of even degree, or

- $G_i$ is a complete graph with an even number of vertices.

Upon further investigation, this characterization is flawed. For example, if we take two triangles and connect them by an edge, that graph is also irreducible. Really, we can make chains of any length with these triangles. Notice that we can do the same thing with any graph with all degrees even, not just with triangles!

If we replace condition $1$ with "$G_i$ is a chain of graphs with vertices of even degree", this characterization is still flawed, as there are irreducible graphs which don't satisfy it.

Maybe this is a dead end. Maybe not?