Posting a second answer with a different approach: Let's start with the equation of an ellipse centered at $(x_0, y_0)$.

$$\left(\frac{x - x_0}{a}\right)^2 + \left(\frac{y - y_0}{b}\right)^2 = 1$$

Or equivalently:

$$b^2x^2 + a^2y^2 - 2b^2x_0x - 2a^2y_0y + (b^2x_0^2 + a^2y_0^2 - a^2b^2) = 0$$

But this doesn't quite match up to the generic conic form $Ax^2 + Bxy + Cy^2 + Dx + Ey + F = 0$ because the $Bxy$ term is missing. So let's introduce an alternate coordinate system $(x', y')$ that doesn't require the $xy$ term.

$$A'x'^2 + C'y'^2 + D'x' + E'y' + F' = 0$$

Let $x = r\cos\theta$ and $y = r\sin\theta$. But rotate the coordinate system so that

$$x' = r\cos(\theta + \phi) = r(\cos\theta\cos\phi - \sin\theta\sin\phi) = x\cos\phi - y\sin\phi$$

$$y' = r\sin(\theta + \phi) = r(\sin\theta\cos\phi + \cos\theta\sin\phi) = y\cos\phi + x\sin\phi$$

Substituting into the alternate coordinate equation gives:

$$A'(x\cos\phi - y\sin\phi)^2 + C'(y\cos\phi + x\sin\phi)^2 + D'(x\cos\phi - y\sin\phi) + E'(y\cos\phi + x\sin\phi) + F' = 0$$

which expands to:

$$(A'\cos^2\phi + C'\sin^2\phi)x^2 + 2(C' - A')\cos\phi\sin\phi xy + (A'\sin^2\phi + C'\cos^2\phi)y^2 + (D'\cos\phi + E'\sin\phi)x + (E'\cos\phi - D'\sin\phi) + F' = 0$$

Plugging in the coefficients from the $xy$-less ellipse equation gives:

$$A = b^2\cos^2\phi + a^2\sin^2\phi$$

$$B = 2(a^2 - b^2)\cos\phi\sin\phi$$

$$C = b^2\sin^2\phi + a^2\cos^2\phi$$

$$D = -2b^2\cos\phi - 2a^2\sin\phi$$

$$E = -2a^2\cos\phi + 2b^2\sin\phi$$

$$F = b^2x_0^2 + a^2y_0^2 - a^2b^2$$

We can derive from these that $A + C = a^2 + b^2$ and $B^2 - 4AC = -4a^2b^2$.

Define the aspect ratio ($R$) of an ellipse as the quotient $\frac{a}{b}$. Or should that be $\frac{b}{a}$? The two values are just reciprocals of each other. Instead of choosing, let's add them.

$$R + \frac{1}{R} = \frac{a}{b} + \frac{b}{a} = \frac{b}{a} + \frac{a}{b}$$

$$\frac{R^2 + 1}{R} = \frac{a^2 + b^2}{ab}$$

But making the substitutions $a^2 + b^2 = A + C$ and $a^2b^2 = \frac{B^2 - 4AC}{-4}$ and rearranging into a polynomial in $R$ gives:

$$(B^2 - 4AC)R^4 + (4A^2 + 2B^2 + 4C^2)R^2 + B^2 - 4AC = 0$$

Applying the Quadratic Formula to solve for $R^2$ gives:

$$\boxed{R^2 = \frac{-(2A^2 + B^2 + 2C^2) \pm 2 (A + C)\sqrt{(A - C)^2 + B^2}}{B^2 - 4AC}}$$

Note that as the curve approaches a parabola ($B^2 - 4AC \to 0$), we get a division by zero, and thus an “infinite” aspect ratio. And if $B = 0$, the above formula simplifies to $R^2 \in \{ \frac{A}{C}, \frac{C}{A} \}$. And for a circle, we simply have $R^2 = 1$.

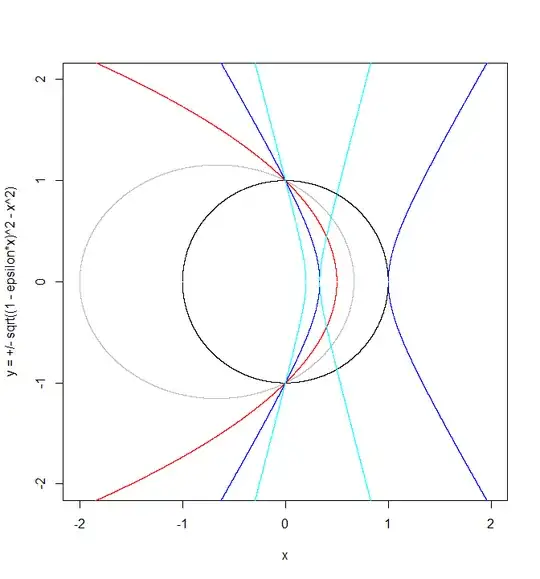

Now, let's find how aspect ratio is related to eccentricity. By plugging in the coefficients from my previous answer, we get:

$$R^2 \in \{ 1 - \varepsilon^2, \frac{1}{1 - \varepsilon^2} \}$$

$$\varepsilon = \pm\sqrt{1 - R^2} \text{ or } \varepsilon = \pm{\sqrt{1 - \frac{1}{R^2}}}$$

But $\varepsilon$ should be a positive real number, so this gives:

$$\boxed{\varepsilon = \begin{cases}

\sqrt{1 - R^2} & \text{if } R^2 \le 1 \\

\sqrt{1 - \frac{1}{R^2}} & \text{if } R^2 \ge 1

\end{cases}}$$

By allowing the aspect ratio $R$ to be either real or imaginary, we can have this formula accommodate all types of conic sections:

- Circle: $R^2 = 1$, $\varepsilon = 0$

- Ellipse: $R^2 > 0$, $0 \le \varepsilon < 1$

- Parabola: $R^2 = 0 \lor R^2 = \infty$, $\varepsilon = 1$

- Hyperbola: $R^2 < 0$, $\varepsilon > 1$