Today I came up with many beautiful results in parabola, but I decided to present the most prominent result in the form of a question on this site, I think it is a really special feature

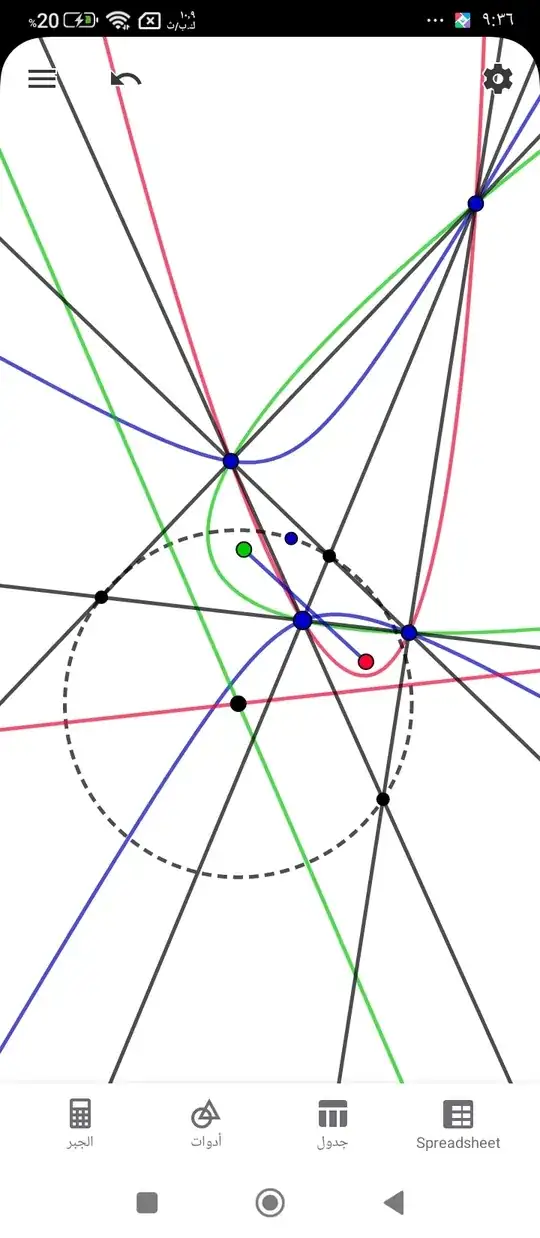

Let's have two parabolas intersecting in four points, these four points form the vertices of a convex quadrilateral, if we draw all the straight lines connecting these four points, we get three additional intersection points, now we draw the circle passing through these three points, this property says that the radius of this circle is equal to the distance between the foci of the parabolas if and only if the guides of the parabolas are perpendicular, or in other words, it happens if and only the intersection of the parabolas at four points located On one circle, is there anyone who can prove it? And is this property known in advance? Please provide any references on the subject

Given: $P$ is a parabola with focus $F_p$ and directrix $\Delta_p$, and $Q$ is a parabola with focus $F_q$ and directrix $\Delta_q$. Let $P \cap Q = { A, B, C, D }$, $\Delta_p \cap \Delta_q = O$, $\overline{AB} \cap \overline{CD} = U$, $\overline{AC} \cap \overline{BD} = V$, and $\overline{AD} \cap \overline{BC} = W$. Let $G$ be the circle passing through points $U$, $V$, and $W$ with a radius $R$.

Requirement 1: Prove that $O$ is the center of $G$.

Requirement 2: Prove that $\Delta_p \perp \Delta_q \iff \overline{F_p F_q} = R$.

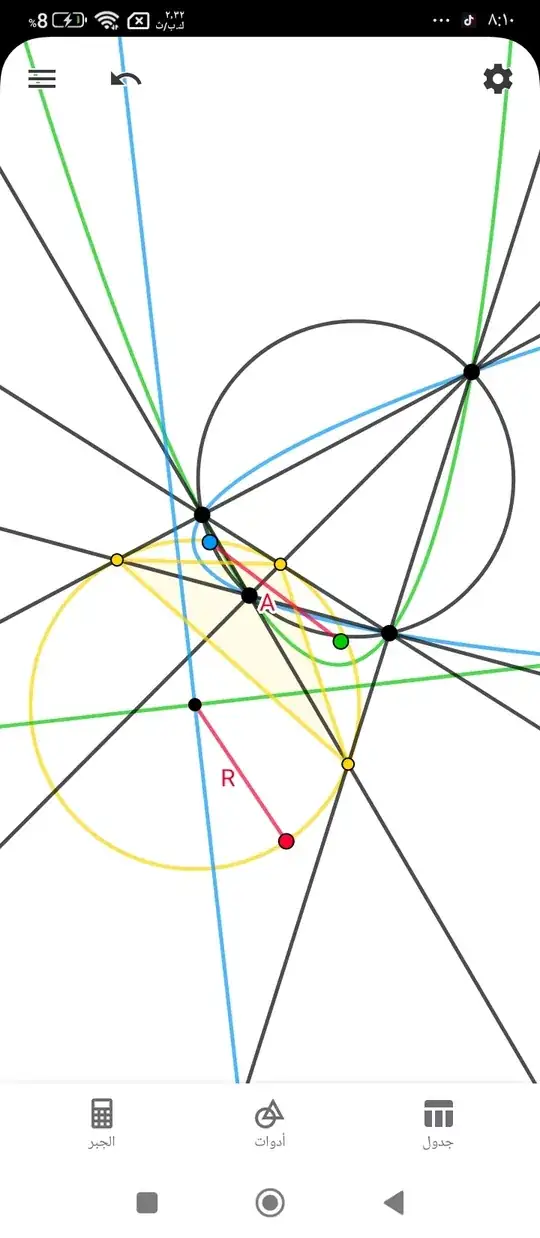

edit: I have finally arrived at the general case of the theorem. We no longer need the orthogonality of the two equivalent segments' directions to find the relationship between $A$ and $R$. There is a simple and elegant algebraic relationship given by $A = R \times \sin(\theta)$, where $\theta$ represents the angle measure between the directions of the two equivalent segments.

New edit: I just discovered a new property related to shape that may be useful in finding a geometric proof

There is a single hyperbola with two perpendicular approaches that passes through the four points where the two parabolas intersect, the center of this hyperbola belongs to the circle we used to explain this theorem