(Note: All images except the $13$-gon are from Antonia Buitrago's 2007 article "Polygons, Diagonals, and the Bronze Mean".)

I. The golden ratio

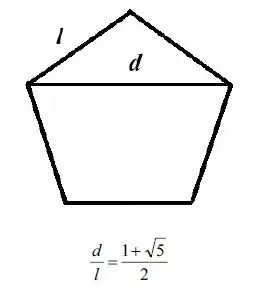

We are familiar with how $\phi$ appears in the regular pentagon,

If the pentagon has unit length $l=1$, then diagonal $d=\frac{1+\sqrt{5}}2.$ But $\phi$ is just the first metallic ratio, or the quadratic root $R_m$,

$$R_m = \frac{m+\sqrt{m^2+4}}2$$

the next is the silver ratio $R_2 = \frac{2+\sqrt{8}}2 = \small{1+\sqrt{2}}\, ,$ the bronze ratio $R_3 = \frac{3+\sqrt{13}}2$, and so on.

Proposal: We generalize the pentagonal case: Using more than one diagonal of a polygon, can we express all $R_m$? It seems the answer is yes.

II. Diagonals

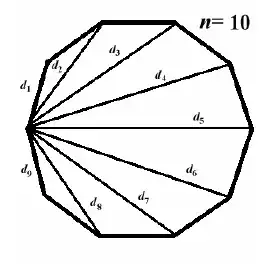

Given a regular polygon, we follow Buitrago and define a particular set of diagonals $d_k$ as "the line segments joining a common vertex $v_0$ to vertex $v_k$". For example,

Hence $d_1$ is from $v_0$ to $v_1$, while $d_2$ is from $v_0$ to $v_2$, and so on. And $d_1 = d_9$ is just the side length of the decagon. The ratio of $d_k$ to $d_1$ is given by,

$$\frac{d_k}{d_1} = \frac{\sin\frac{k\,\pi}n}{\sin\frac{\pi}n} = \sqrt{\frac{1-\cos\frac{2k\pi}n}{1-\cos\frac{2\pi}n}}$$

For the regular $n$-gon with unit side length $d_1 = 1$, define these diagonals as,

$$D_n(k) = \frac{\sin\frac{k\,\pi}{n}}{\sin\frac{\pi}{n}}\qquad\qquad$$

III. Data

$$\small{\begin{align} \phi=\frac{1+\sqrt{5}}2\; &= D_5(2)\\ 1+\sqrt{2}=\frac{2+\sqrt{8}}2\; &= D_4(1)+D_4(2) \,=\, D_8(3)\\ U_{13}=\frac{3+\sqrt{13}}2 &= \color{blue}1D_{13}(1)+D_{13}(3)+D_{13}(4)-D_{13}(5)\\ \phi^3=\frac{4+\sqrt{20}}2 &= D_{5}(1)+D_{5}(2)+D_{5}(3) \,=\, D_{10}(1)+D_{10}(5)\\ U_{29} = \frac{5+\sqrt{29}}2 &= \color{blue}2D_{29}(1)+D_{29}(2)+D_{29}(3)-D_{29}(4)-D_{29}(7)+\dots+D_{29}(14)\\ 3+\sqrt{10}=\frac{6+\sqrt{40}}2 &= 3D_{20}(1)+D_{20}(4)+D_{20}(6)-2D_{20}(8)+D_{20}(10)\\ U_{53}=\frac{7+\sqrt{53}}2 &= \color{blue}3D_{53}(1)+D_{53}(2)+D_{53}(3)-D_{53}(6)-D_{53}(7)+\dots+D_{53}(26)\\ 4+\sqrt{17}=\frac{8+\sqrt{68}}2 &= 3D_{17}(1)-2D_{17}(2)+2D_{17}(5)-2D_{17}(7)+2D_{17}(8) \end{align}}$$

and so on, where $U_n$ is a fundamental unit. It seems it is easy to predict the coefficient of $D_n(1)$ when $n=m^2+4$ is prime. (Curiously, I couldn't find $3+\sqrt{10}$ in the decagon. I had to use the $20$-gon.)

IV. The 13-gon

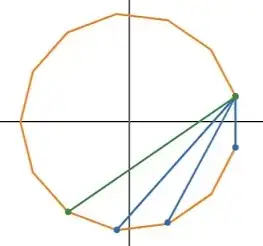

A picture is worth a thousand words. Assume a $13$-gon with unit side length,

Let the common vertex be $v_0$ which connects to vertices $v_1, v_3, v_4, v_5$. Then the sum of the three blue lines minus the green line is the bronze ratio,

$$\left(\frac{\sin\frac{1\pi}{13}}{\sin\frac{\pi}{13}}\right)+\left(\frac{\sin\frac{3\pi}{13}}{\sin\frac{\pi}{13}}\right)+\left(\frac{\sin\frac{4\pi}{13}}{\sin\frac{\pi}{13}}\right)-\left(\frac{\sin\frac{5\pi}{13}}{\sin\frac{\pi}{13}}\right)= \frac{3+\sqrt{13}}2$$

Or in the notation of the previous sections,

$$D(1)+D(3)+D(4)-D(5) = \frac{3+\sqrt{13}}2$$

where $D(k)=D_{13}(k)$ and the subscript has been suppressed for brevity. Image is courtesy of the Desmos Polygon Calculator.

V. Question

What is the general formula to express the metallic ratios,

$$R_m = \frac{m+\sqrt{m^2+4}}2$$

in terms of these diagonals $D_n(k)$, especially if $n=m^2+4$ is prime?

For example, since $D_n(1)=1$, how do we generate the next $\frac{13-1}4=3$ numbers $k=(3, 4, 5)$, or $\frac{17-1}4=4$ numbers $k=(2, 5, 7, 8)$, or $\frac{29-1}4=7$ numbers $k=(2, 3, 4, 7, 10, 12, 14)$ from first principles?