I would like to propose the following conjecture and seek insights or references related to it:

Conjecture:

Every non-zero integer $n$ can be expressed as the difference of a semiprime $q$ and a prime $p$, that is, $$n=q−p,$$

where:

q is a semiprime (the product of two primes, not necessarily distinct), and

p is a prime number.

Numerical Verification:

To gather empirical support for this conjecture, I conducted extensive numerical experiments within the range $−10,000,000≤n≤10,000,000$ (excluding $n=0$). In every case within this range, I successfully found pairs of $p$ and $q$ satisfying the equation $n=q−p$. No counterexamples were observed.

Example: For instance, when $n=15$:

Choose p=7 (a prime),

Then q=7+15=22, which is a semiprime (22=2×11).

Thus, $15=22−7$.

Questions:

In seeking a proof or counterexample for this conjecture, what approaches or existing theories would be effective? Especially, I would appreciate advice from the perspectives of additive number theory or multiplicative number theory.

Additional Information:

Implementation Details:

The numerical experiments were conducted using a Python program optimized with the Sieve of Eratosthenes for prime generation and parallel processing to handle large ranges efficiently. While I can provide the code upon request, the focus here is on the mathematical aspect of the conjecture.

Exclusion of Zero:

The case n=0 is excluded since it would require q=p, and while p is prime, q would need to be semiprime, which only occurs if p itself is a semiprime. Given that primes greater than 2 are not semiprimes, n=0 serves as an inherent exception to the conjecture.

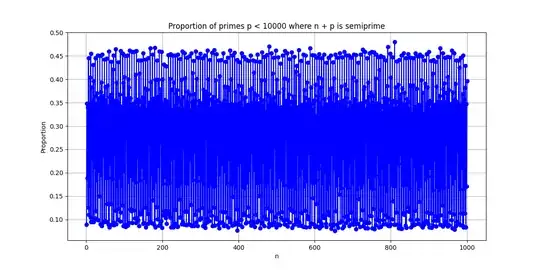

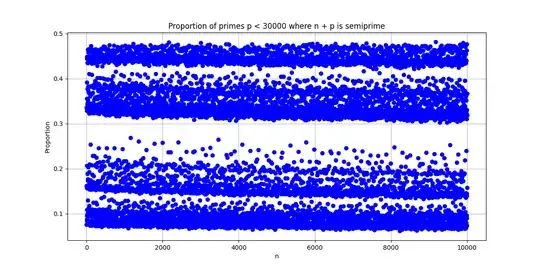

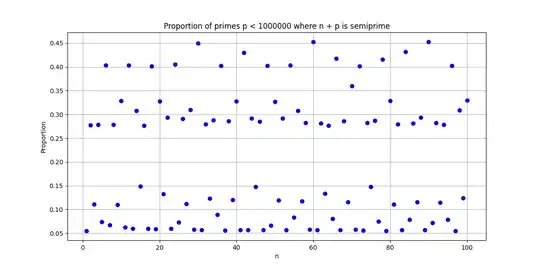

Graphical Representation:

Upon observation, there is a tendency for

$n$ to stick to the upper range when it is a multiple of $6$ (Especially multiples of $30$), and to the lower range when $n$ is a prime number.

Motivation

Motivation

The motivation for this conjecture stems from the robustness of semiprimes used in RSA encryption. Specifically, semiprimes are known for their resistance to division by prime numbers, as they rarely divide evenly. This led me to consider a different approach: what if, instead of division, we use subtraction? Given that semiprimes do not divide cleanly, I hypothesized that their differences with primes might display some kind of pattern or periodicity, resulting in jumps to other numbers.

From this idea, I further speculated that these "jumps" could cover all integers in a somewhat uniform manner. However, recognizing that semiprimes and primes belong to different classes, it became clear that expressing zero was not feasible. Thus, zero was excluded from the conjecture's conditions.

If proven, this conjecture could offer new perspectives in number theory, with possible connections to cryptographic systems like RSA encryption.

Additionally, this conjecture may inherently include basic memory management functionality.

I appreciate any feedback, references, or discussions that can shed light on the validity and potential avenues for this conjecture. Thank you!