You don't need to use the concept of martingale to prove that the proportion of blue balls in the urn (hereafter PBBITU) follows the beta distribution. The similarity is in the formulas used in both proofs.

Next, as we will see later, we don't need $r$ and $b$ to be integers; being positive is enough. Thus, we divide both by $\alpha$:

$$r' := \frac{r}{\alpha}; \; b' := \frac{b}{\alpha}$$

and assume that we initially have $r'$ red balls and $b'$ blue balls and that we add one ball at a time. This scaling won't affect the PBBITU.

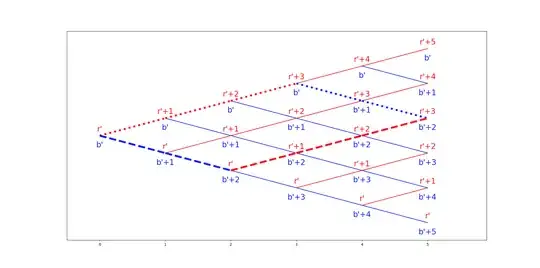

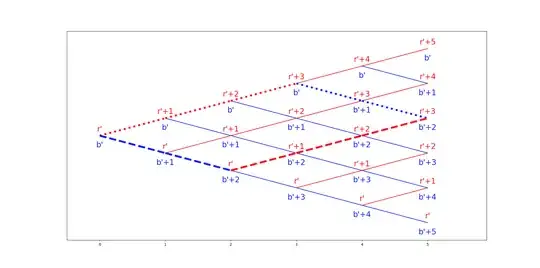

If you plot the dynamics of the number of balls of each colour, you get a recombining binomial tree, as in the picture below.

We can go up (draw a red ball) or down (draw a blue ball) at each node. Thus, if you have $T$ "forks", you have $2^T$ distinct paths to a node at time $T$. The plot shows two paths to $(b'+2, r'+3)$, rrrbb and bbrrr; the total number of paths to $(b'+2, r'+3)$ is $\binom{5}{2} = \frac{5!}{2!(5-2)!} = 10$. In the general case, there are $\binom{T}{B} = \frac{T!}{B!(T-B)!}$ paths with $B$ blue balls and $T-R$ red balls.

The probability of following a path that leads to $b'+B, r'+(T-B)$ is $$\frac{\prod_{j=0}^{B-1}(b'+j)\prod_{i=0}^{T-B-1}(r'+i)}{\prod_{k=0}^{T-1}(b'+r'+k)}$$ Let me know if you need me to write it explicitly.

Thus, the (overall) probability to get to $b'+B, r'+(T-B)$ at $T$ is

$$p_T\left(b'+B, r'+(T-B)\right)=\underbrace{\binom{T}{B}}_{\text{How many paths lead to }b'+B, r'+(T-B)} \underbrace{\frac{\prod_{j=0}^{B-1}(b'+j)\prod_{i=0}^{T-B-1}(r'+i)}{\prod_{k=0}^{T-1}(b'+r'+k)}}_{\text{The probability to follow any of these }\binom{T}{B}\text{ paths}}=\star$$

Now, what's left is to prove that the distribution with this density converges to beta distribution. The proof of this convergence will be similar to Polya's urn model - limit distribution. If we use $\Gamma(s+1) = s\Gamma(s)$ property of Gamma function

\begin{align}

\Gamma(b'+B)&=\prod_{j=0}^{B-1}(b'+j)\Gamma(b')\\

\Gamma(r'+T-B)&=\prod_{i=0}^{T-B-1}(r'+i)\Gamma(r')\\

\Gamma(b'+r'+T)&=\prod_{k=0}^{T-1}(b'+r'+k)\Gamma(b'+r')

\end{align}

and develop the binomial coefficient, we obtain

\begin{align}

\star&=\frac{T!}{B!(T-B)!} \frac{\Gamma(b'+B)\Gamma(r'+T-B)\Gamma(b'+r')}{\Gamma(b')\Gamma(r')\Gamma(b'+r'+T)}\\

&=\frac{\Gamma(b'+r')}{\Gamma(b')\Gamma(r')} \frac{\Gamma(b'+B)/B! \; \Gamma(r'+T-B)/(T-B)!}{\Gamma(b'+r'+T)/T!}=\spadesuit\\

\end{align}

Next, we use the Beta function and introduce $E_n(z) = \frac{\Gamma(n+z)}{n!n^{z-1}}$

\begin{align}

\spadesuit&=\frac{1}{B(b', r')} \frac{E_B(b') B^{b'-1} \; E_{T-B}(r') (T-B)^{r'-1} }{E_{T}(b'+r') T^{b'+r'-1} }\\

&=\frac{1}{B(b', r')} \frac{1}{T} \left(\frac{B}{T}\right)^ {b'-1} \left(1-\frac{B}{T}\right)^ {r'-1}\frac{E_B(b') E_{T-B}(r')}{E_{T}(b'+r')}

\end{align}

Now, to prove that the discrete distribution with these probabilities converges to a beta distribution (see this question for the rigorous definition and proof), let's compute the moment-generating function:

\begin{align}

\mathbb{E}\left[e^{\lambda X_T}\right]&= \frac{1}{B(b', r')} \frac{1}{T} \sum_{B=0}^T e^{\lambda \frac{b'+B}{b'+r'+T}} \left(\frac{B}{T}\right)^ {b'-1} \left(1-\frac{B}{T}\right)^ {r'-1}\frac{E_B(b') E_{T-B}(r')}{E_{T}(b'+r')}

\end{align}

We need to prove that this function converges to the moment-generating function of beta distribution:

$$\mathbb{E}\left[e^{\lambda X_\infty}\right]

?= \frac{1}{B(b', r')} \int_{0}^{1} e^{\lambda p} p^{b'-1}(1 - p)^{r'-1} dp$$

The last-but-one is similar to the Riemann sum of the integral just above $\left(\frac{B}{T} \text{ becomes } p \text{ and } \frac{1}{T} \text{ becomes } dp \right)$.

Since we integrate over a finite interval, it's sufficient to prove that

\begin{align*}

e^{\lambda \frac{B}{T}} \xrightarrow[T \to \infty]{} e^{\lambda \frac{b'+B}{b'+r'+T}}\\

\frac{E_B(b') E_{T-B}(r')}{E_{T}(b'+r')} \xrightarrow[T-B, B \to \infty]{} 1\\

\end{align*}

Taylor expansion of expanentials can prove the former. The latter can be demonstrated using Stirling's approximation and Stirling's formula of the Gamma function:

\begin{align*}\frac{n!}{\sqrt{2\pi n}\frac{n^n}{e^n} } \xrightarrow[n \to \infty]{} 1 \text{ and }

\frac{\Gamma(x+1)}{\sqrt{2\pi x}\left(\frac{x}{e}\right)^x} \xrightarrow[x \to \infty]{} 1 \\ \strut \\ \end{align*}

Therefore, for $E_n(z) = \frac{\Gamma(n+z)}{n!n^{z-1}}$ we have

$$\frac{E_n(z) \sqrt{2\pi n}\frac{n^n}{e^n}}{\sqrt{2\pi (n+z-1)}\left(\frac{n+z-1}{e}\right)^{n+z-1}} n^{z-1} = \frac{\Gamma(n+z)\sqrt{2\pi n}\frac{n^n}{e^n}}{n!\sqrt{2\pi (n+z-1)}\left(\frac{n+z-1}{e}\right)^{n+z-1}} \xrightarrow[n \to \infty]{} 1$$

Rearranging the terms of the first expression results in

$$\frac{E_n(z) {e^{z-1}}}{\left(\frac{n+z-1}{n}\right)^{n+z-0.5}} = \frac{E_n(z) {e^{z-1}}}{\left(\left(\frac{n+z-1}{n}\right)^{\frac{n+z-0.5}{z-1}}\right)^{z-1}} \xrightarrow[n \to \infty]{} 1$$

Factoring in the definition of $e$, we conclude that $E_n(z) \xrightarrow[n \to \infty]{} 1$. Therefore, the latter statement is correct.