I am curious whether it's possible to prove $ \operatorname{rot}(\operatorname{rot} A) $ using differential forms, similar to the example shown below. I believe the Hodge star operator might play a role in this, but I would appreciate an explanation if anyone is familiar with this approach.

Example of a proof using differential forms:

$$ \mathrm{div}(fa) = (\nabla f) \cdot a + f (\nabla \cdot a) $$

Let $ \lambda_v $ be a 3-form and $ \omega_v $ a 2-form, both with components corresponding to the vector $ v $.

$$ \lambda_{\mathrm{div}(fa)} = d(f\omega_a) = df \wedge \omega_a + f(d\omega_a) \quad (\text{by the product rule}) \\ = \lambda_{\mathrm{grad} f \cdot a} + \lambda_{f\mathrm{div}(a)} \\ = \lambda_{\mathrm{grad} f \cdot a + f\mathrm{div}(a)} $$

Regarding the proof of $ \operatorname{rot}(\operatorname{rot} A) $:

I think there might be a way to prove it using the following expression:

$$ \omega_{\operatorname{rot}(\operatorname{rot} A)} = d(*d\nu_A) = ? $$

Here, $ \nu_A $ is a 1-form whose components correspond to those of $ A $. I suspect the properties of the Hodge star operator could be useful here. While I could verify this calculation component-wise without using differential forms, I am searching for a more efficient, conceptual method that fully leverages the power of differential forms, similar to the approach used in the example above.

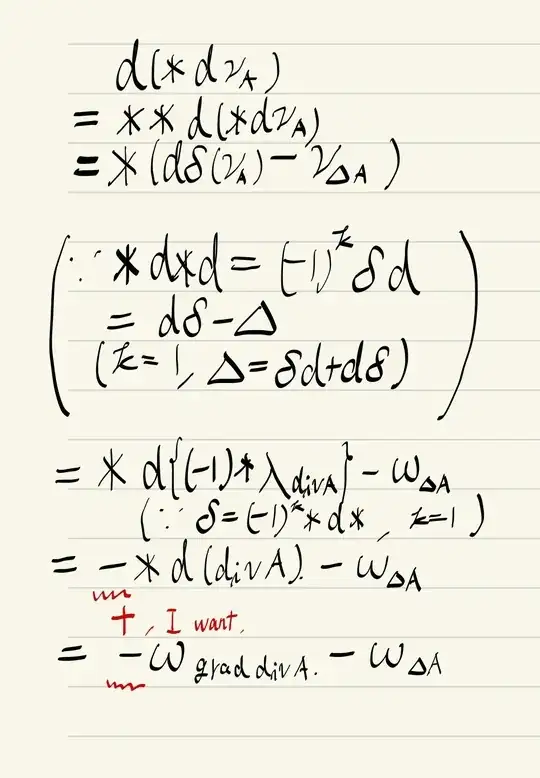

I have also considered using the Laplace-de Rham operator, but when I worked through the calculation, I encountered sign issues and didn't obtain the desired result(like the picture below). I am not entirely confident in my reasoning and would appreciate any insights. If anyone could provide a clear proof or point out where my calculation may have gone wrong, that would be extremely helpful.