A:

The first thing to note is that the 'hypotheses' that the website talks about are not the statements in $\Gamma$. The statements in $\Gamma$ are often referred to as premises. Both natural deduction (ND) style proofs and Hilbert Calcukus (HC) style proofs can have premises, and typically you would start any proof by listing those premises.

The 'hypotheses' that the website refers to are assumptions that you can make at any point during a proof, but which later on need to be discharged. This can only be done in ND style proofs ... in HC style proofs there is no such thing.

By the way, the premises of a proof can also be seen as assumptions, but these are not temporary assumptions like the 'hypotheses' are.

The use of temporary assumptions is probably best illustrated through a 'Fitch-style' natural deduction system, where you have the discharge the assumptions in the reverse order as in which you introduced them ('Last In First Out'). In such a system we can thus talk about subproofs ... and subproofs within subproofs. Indeed, as far as proof systems go, the nested structure of these kind of proofs closely mirror the way humans typically do something like a math proof.

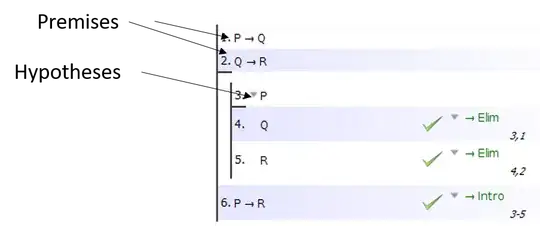

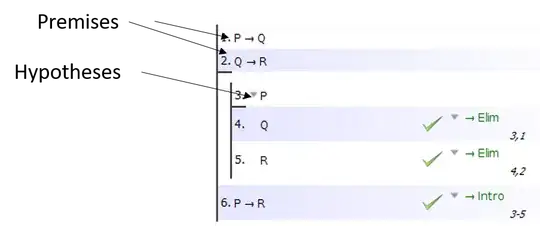

Below are some examples. First, a proof of $\{ P \to Q, Q \to R \} \vdash_{ND} P \to R$:

So in this proof we have two hypotheses (often called 'premises'), but in order to prove the conclusion, we'll start a subproof on line 3 where we make an additional assumption of $P$.

So note: $P$ is not part of $\Gamma$ (which is just $\{ P \to Q, Q \to R \}$) and thus $P$ is not a premise. $P$ is an 'additional' and temporary assumption as indicated by the indentation.

Now, given additional assumption $P$, we can now quickly infer $Q$, and thus $R$, with 2 quick Modus Ponens's. But note: we are of course not saying that we have proven $Q$ and $R$. That is: $Q$ and $R$ do not follow from the premises $P \to Q$ and $Q \to R$. However, they do follow from those premises together with the additional assumption of $P$.

Indeed, all of this happen inside the subproof, which is the whole structure of lines 3 through 5, and is marked by the vertical line and indentation.

OK, but now on line 6 we 'jump out' or 'close' the subproof, thereby discharging the temporary assumption $P$. However, since the subproof showed that $R$ can be proven once you assume $P$, we can now point to the subproof from the outside, and conclude $P \to R$. This is a really common proof technique called Conditional Proof.

So notice that the rule used on line 6 is a rule that infers something from a whole subproof (as indicated by 3-5), and not from individual sentences. Again, this is not something that HC systems can do: in a HC system, you can only infer statements from other statements.

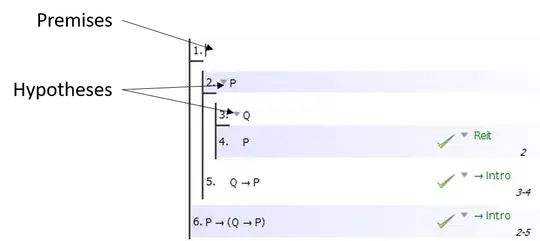

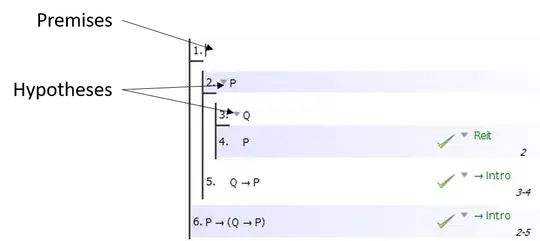

Here is another example that has no premises, but that uses nested subproofs to prove a statement (a statement that happens to be a commonly used axiom in Hilbert systems):

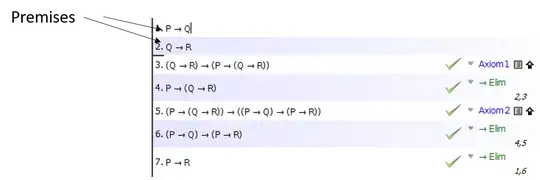

Compare this with a typical HC proof. In a HC proof, there are no temporary or additional assumptions that you make in addition to the original premises in $\Gamma$. So there are no subproofs either, and inference are strictly from statement to other statements. You can, however, introduce an axiom at any point in a HC proof.

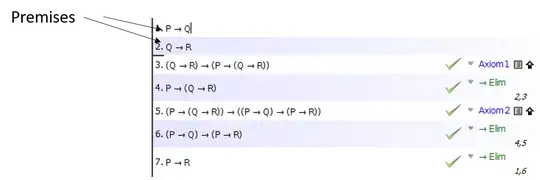

Here is an example of a HC proof for $\{ P \to Q, Q \to R \} \vdash_{HC} P \to R$:

So note: no additional assumptions, no 'hypothetical reasoning': just a long sequence of statements. Proofs are completely 'flat' and have no 'structure' like ND proofs have. But it is exactly these 'structures' that help us humans think about things, which is why ND systems are typically far easier for us to work with than HC systems.

Of course, something HC systems do have, but (typically) ND systems do not, is axioms. Like hypotheses in an ND proof, axioms can be introduced at any point during a HC proof ... but it is not an assumption, because an axiom is a logical truth. Indeed, the 'reasoning from truth' slogan from that website refers to the fact that HC systems typically work with logical truths only. That is, think of axiom systems for logic as the counterpart to axioms for geometry, or axioms for numbers, or axioms for sets: instead of proving geometrical, number-theoretic, or set-theoretic truths, in an axiomatic system like HC we prove logical truths. Indeed, typically an HC proof has no premises at all, and thus every statement in such a proof would thus be a logical truth.

In fact, the 'game' of working with axioms is of course to try and boil down everything to just a few elementary principles, and thus a typical HC systems ends up with just a few axioms, a few inference principles, and a few logical operators.

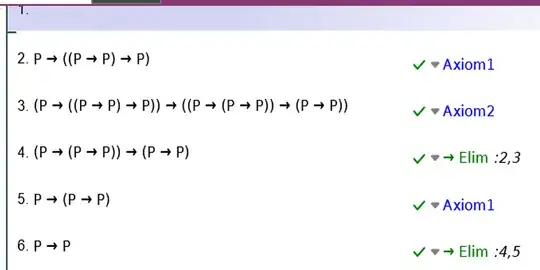

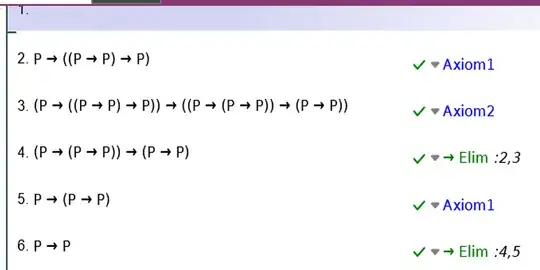

And that, by the way, is another reason why HC systems are so hard to work with for us humans! Consider, for example, the acrobatics you have to go through just to prove something as simple as $P \to P$ in one of the most popular HC systems called the Lukasiewicz system:

And compare that to a proof in ND, where of course we exploit the ability to make an assumption:

(that is: once we assume $P$, we see that if $P$ ... well, then $P$! ... OK, done!)

B: Yes. (assuming the specific Hilbert-style proof system and the natural deduction style proof system are both sound and complete)

In fact, there is an important meta-logical result, called the Deduction Theorem, that you can prove for any sound and complete Hilbert system $H$ (and that uses the $\to$), which is that if $\Gamma, \phi \vdash_H \psi$, then $\Gamma \vdash_H \phi \to \psi$. The proof of the Deduction Theorem is typically based on showing a small algorithm for how to transform a Hilbert proof that shows $\Gamma, \phi \vdash_H \psi$ into a Hilbert proof that shows $\Gamma \vdash_H \phi \to \psi$.

This result immediately relates to the transformation from natural deduction style proof to Hilbert system style proof: if in a natural deduction style proof you ever make an assumption $\phi$, and use that to derive $\psi$, then (in most natural deduction style systems) you can conclude $\phi \to \psi$ while discharging $\phi$ as an assumption.

Now, the complete transformation from a natural deduction style proof into a Hilbert style proof will depend on the specifics of the rules and axioms used. Indeed, one thing to think about is that one system may use logical connectives that the other system does not, in which case you will need to define operators in terms of other operators, and treat sentences accordingly. For example, many Hilbert systems stick to just the $\to$ and $\neg$ operators, and so for a natural deduction system proof that uses $\land$ and $\lor$ you will first need to replace all instances of those operators with an equivalent expression using just $\to$ and $\neg$.

You can look at this post for an example of how you can systematically transform a natural deduction proof (that happily uses only $\to$'s and $\neg$'s) into a Hilbert-style proof

For the other way around: a Hilbert style proof can be systematically transformed into a natural deduction style proof simply by proving any of the axioms of the Hilbert system .. this is typically very straightforward. In fact, in the second example proof above I already showed how you would do this for a common Hilbert system axiom. Other axioms are likewise easy to prove.

As far as emulating the inference rules go: MP is often already a rule in any regular natural deduction system, so that's easy. And the 'substitution rule' isn't so much a separate rule of inference, but rather states that for any of the axioms of the Hilbert system you can fill in any statements for any of the variables involved in the axiom .. which simply means that you can have many different instances of the same axiom, and that also means that you need to prove any such instance with a separate proof in the natural deduction system .. but the basic pattern will be exactly the same. For example, the proof above shows how to prove $P \to (Q \to P)$, but the proof of something like $(A \to B) \to (\neg C \to (A \to B))$ will follow the exact same abstract format, since natural deduction systems use this very same substitution principle.