I'm trying to solve the following problem from Aluffi's Algebra: Chapter 0:

Show that there is a surjective homomorphism $\mathbb Z * \mathbb Z \to C_2 * C_3$.

This problem has been discussed on the site before, but not (I think) from the particular angle that I will put forward here.

At this point in the text we do not have any explicit constructions of $\mathbb Z * \mathbb Z$ and $C_2 * C_3$; we know only that they are coproducts in $\mathsf{Grp}$. Hence I have been trying to solve the problem by using universal properties.

As seen below, I have been able to prove this: there exists an epimorphism $\mathbb Z * \mathbb Z \to C_2 * C_3$. I have gleaned from the internet that epimorphisms in $\mathsf{Grp}$ are also surjective, but the proof of that fact is far beyond my current knowledge (and beyond what has been covered in the text).

Is there some other (hopefully more elementary) way to rescue my (attempted) proof?

My attempt

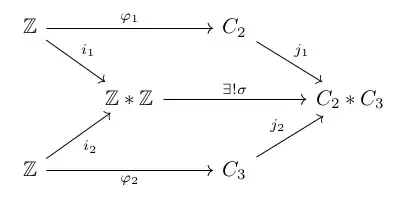

Consider the following diagram:

Here $i_1, i_2, j_1, j_2$ are the canonical homomorphisms associated with the two coproducts, and $\varphi_1, \varphi_2$ are surjective homomorphisms (there are obvious ones to choose from). By the universal property of the coproduct there is a unique homomorphism $\sigma$ making the diagram commute.

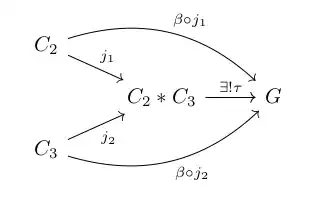

Next, let us show that $\sigma$ is an epimorphism. Hence let $G$ be an arbitrary group and $\beta, \beta': C_2 * C_3 \to G$ be arbitrary homomorphisms satisfying $\beta \circ \sigma = \beta' \circ \sigma$. Then

$$\beta \circ j_1 \circ \varphi_1 = \beta \circ \sigma \circ i_1 = \beta' \circ \sigma \circ i_1 = \beta' \circ j_1 \circ \varphi_1,$$

which implies that $\beta \circ j_1 = \beta' \circ j_1$, since $\varphi_1$ is (clearly) an epimorphism. Similarly $\beta \circ j_2 = \beta' \circ j_2$. Again by universal property, there is a unique homomorphism $\tau$ making the following diagram commute:

But setting $\tau = \beta$ or $\tau = \beta'$ both make the diagram commute; hence $\beta = \beta'$. This shows that $\sigma$ is an epimorphism.

Not yet proven: $\sigma$ is surjective.

Remark

I notice now that there is a very similar solution suggested here. However, it has the same problem as mine; it only shows that there is an epimorphism.