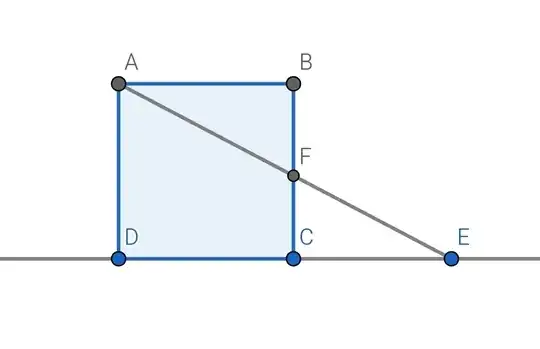

ABCD is a unit square. Construct a point E on DC (extended) such that AE intersects BC at F with EF = 1.

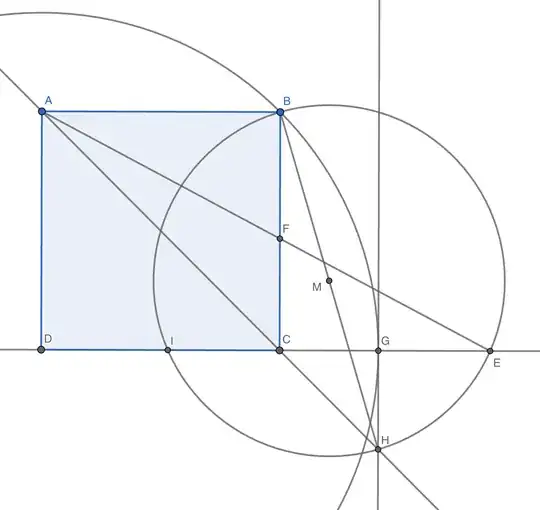

After trying for long, the only solution I could find was to solve for the length of $CE$ algebraically (it turns out to be $\frac{1}{2} (-1 + \sqrt{2} + \sqrt{2 \sqrt{2} - 1})$ ) and then construct that length, which can be done because it is possible to take square root of any arbitrary number via geometric construction.

However, this approach is more algebraic than geometric, and I think that it undermines the style of geometric constructions. I am looking for a better solution to this problem.

EDIT:

The length of $CE$ can be found (by using triangle similarity) to be $\frac{1}{2} (-1 + \sqrt{2} + \sqrt{2 \sqrt{2} - 1})$. This can easily be constructed, thus solving the problem. However, to find out the value of $CE$, I had to solve a 4-degree polynomial (using Wolfram|Alpha).

This method seems (to me), to be kind of brute-forcing a geometrical construction problem. Generally, such problems can be solved by using innovative constructions and using patterns in the question. I am looking for a solution where geometric reasoning is used, instead of resorting to algebraic techniques.

EDIT #2:

After reading @heropup's comment below his answer, I think I can specify my question a little better. I am looking for a synthetic geometric proof, as opposed to the analytic method of solving for the length of $CE$.