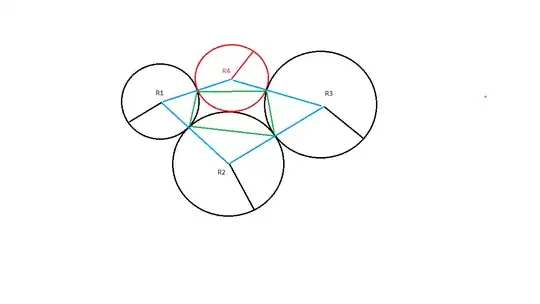

Consider following constellation of four adjacent circles.

Question:(Initial question doesn't give an unique solution; see edit) Assume we know the radii $R_1,R_2,R_3$. Is there a geometric/synthetic way to determine the radius $R_4$ of the red circle.

Ideas: I tried to draw auxilary lines and embedded the green and blue quadrilaterals. Using that each triangle inside each circle bounded by two blue and one green lines is an isosceles triangle, and from this it's easy to deduce that the opposite angles of the green quadrilateral add up to 180 deg. Note sure if that helps.

#EDIT: As Ethan Bolker & Lieven correctly observed, the radii of the three black circles not alone determine the red circle (neither its radius, not its position). Argument: There is "rolling degree" of freedom for left or right circles.

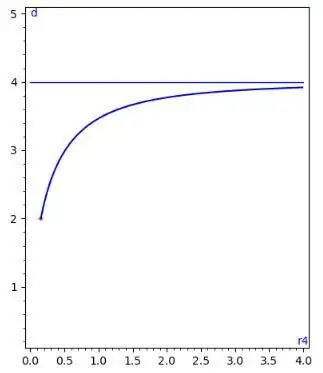

What, if we impose additional assumption by fixing a concrete angle of blue quadrilateral at at center of $R_2$. Can we then determine $R_4$ and the angles of blue quadrilateral at center of $R_4$?