1. Restatement of the Question to Make it Easier to Reference in the Answer

The smallest root of a polynomial is defined as the root which has the smallest absolute value. Consider the polynomial $a_0 + a_1 x + a_2 x^2 + \cdots + a_n x^n$. I observed that if $a_n$, is the sequence of natural numbers then the smallest root of the polynomial

$$1 + 2x + 3x^2 + 4x^3 + \cdots + (n+1)x^{n} \tag 1$$

is real if $n$ is odd and it is complex $n$ is even. But but if $a_n$ is the sequence of prime numbers and $n \ge 14$ then the smallest root of

$$2 +3x + 5x^2 + 7x^3 + \cdots + p_{n+1}x^n \tag 2$$

is always complex for all values up to $14 \le n \le 1200$. Beyond this I have verified the claim for $n$ at random values up to $12,000$ (Computation gets slower as $n$ increases). Clearly there is something about prime numbers which prevent the polynomials from having a real smallest root if the degree of the polynomial is $14$ or higher.

Question 1: Is it true that if the coefficients of a polynomial of degree $14$ or higher is the sequence of prime numbers and than its smallest root is always complex?

Question 2: Why do the smallest root alternate between real of complex depending parity if the coefficients are natural numbers but not for primes?

2. Solution Steps

Consider first in Equation 1 the simple case

$1+2x=1+2\,r\,e^{i\,\theta}=0$ where

$i=\sqrt{-1}$ using [Euler's formula][1]

Clearly, it only has one root with

$r=\frac1{2}$ and

$e^{i,\pi}=-1$ so that this root is

$x_1=-\frac1{2}$ where the subscript

$x_i$ is used to denote the highest power in the polynomial

$\sum_{n=0}^{n=i} x^n=0$. When

$i=0$,

$1\ne 0$. When

$i\in\{\text{Odd Counting Numbers}\}$ then the highest power of

$x$ is odd. Now all polynomials or order

$i$ (of the type in the question) have

$i$ solutions. But the key question is if there is a *real-solution*, because if so, then here the real solution is the smallest root. Consider from Equation 1:

$$

1+2\,x+3\,x^2=0

$$

The highest term

$x^2$ is *even* and therefore for real

$x$ is always positive. This is a parabola so the derivative can be taken to determine its minimum.

$$

6x+2=0 \underset{implies}\implies x=-\frac1{3}

$$

Then

$$

1+2\,x+3\,x^2=1+2\,\left(-\frac1{3}\right)+ 3 \left(-\frac1{3}\right)^2

=1-\frac{2}{3}+\frac{3}{9}=\frac{2}{3}

$$

So the minimum in this case occurs for a positive value of

$1+2\,x+3\,x^2$. That means that the polynomial has a real minimum for a sum of positive quantities, and **there is no real root that evaluates to zero**. I believe this concept can be extended to address the rest of the question, but I need more time to complete this route towards a solution.

For now, I am marking the response as a Community wiki.

3. Solution Steps Towards **Question 1**: Is it true that if the coefficients of a polynomial of degree $14$ or higher is the sequence of prime numbers and than its smallest root is always complex?

To start by solving Question 1:

Question 1: Is it true that if the coefficients of a polynomial of degree $14$ or higher is the sequence of prime numbers and than its smallest root is always complex?

Applying Descartes's Sign Rule (see Appendix), the coefficients of degree of $14$ or higher is the sequence of prime numbers then we have:

$$f\left(x\right)=2+3\,x+5\,x^2+7\,x^3+11\,x^4+13\,x^5+\\

+17\,x^6+19\,x^7+23\,x^8++29\,x^9+31\,x^{10}+37\,x^{11}+\\

+41\,x^{12}+43\,x^{13}+47\,x^{14}+\dots$$

Since the sign of all coefficients is positive, and the smallest coefficient is $2$ there are no positive real roots where $\left.f\left(x\right)\right|_{x\ge 0}=0$. It is fairly obvious to see this result since each term is greater or equal to zero (going further and further away from a root) and $2>0$. However, the remaining question is what is the result in terms of roots for $x<0$.

I am still working on that question. I am still working on fully solving Question 2.

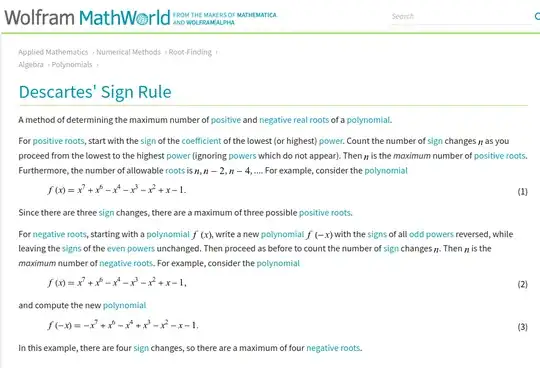

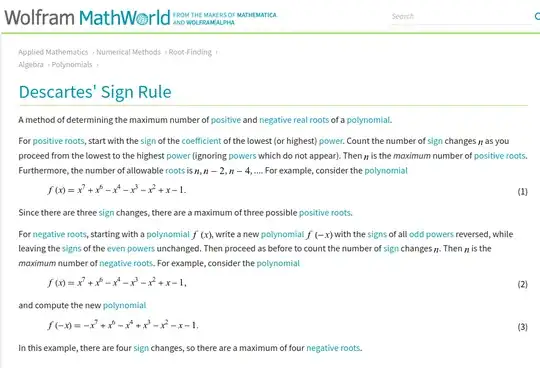

4. Appendix: Descartes's Sign Rule

The application of Descartes' Sign Rule might greatly assist this effort as quoted in the screen-shot below. If there is a situation that there are no positive roots and no negative roots, then all roots are complex and therefore the minimal root is complex.